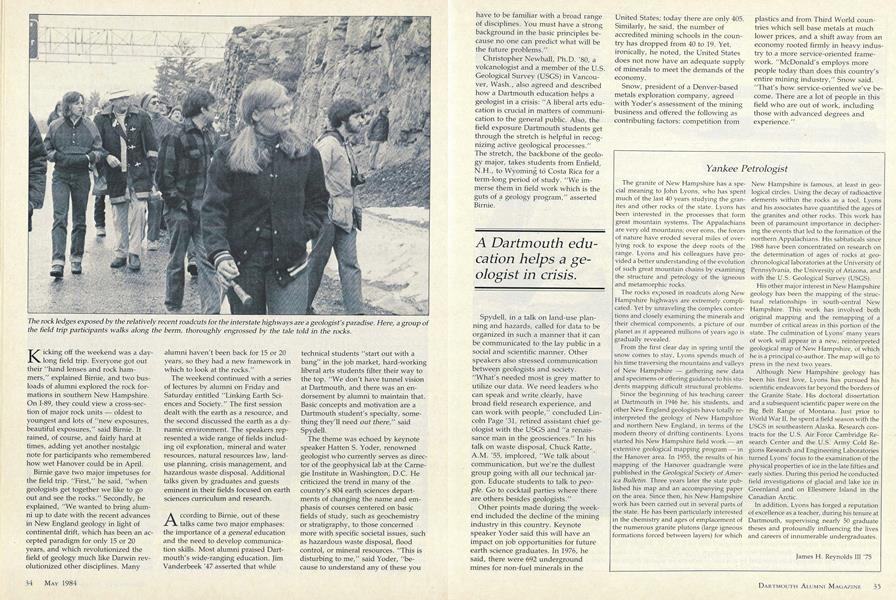

The granite of New Hampshire has a special meaning to John Lyons, who has spent much of the last 40 years studying the granites and other rocks of the state. Lyons has been interested in the processes that form great mountain systems. The Appalachians are very old mountains; over eons, the forces of nature have eroded several miles of overlying rock to expose the deep roots of the range. Lyons and his colleagues have provided a better understanding of the evolution of such great mountain chains by examining the structure and petrology of the igneous and metamorphic rocks.

The rocks exposed in roadcuts along New Hampshire highways are extremely complicated. Yet by unraveling the complex contortions and closely examining the minerals and their chemical components, a picture of our planet as it appeared millions of years ago is gradually revealed.

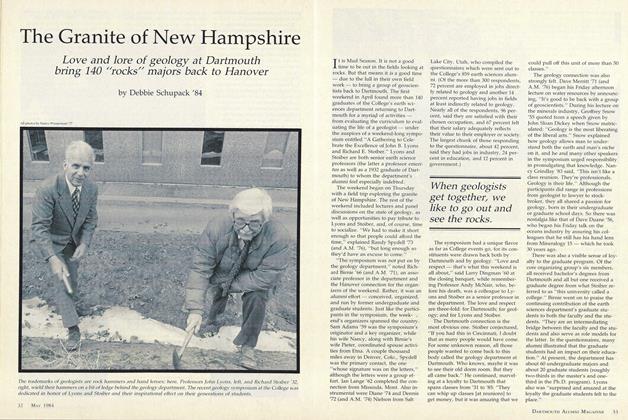

From the first clear day in spring until the snow comes to stay, Lyons spends much of his time traversing the mountains and valleys of New Hampshire gathering new data and specimens or offering guidance to his students mapping difficult structural problems.

Since the beginning of his teaching career at Dartmouth in 1946 he, his students, and other New England geologists have totally reinterpreted the geology of New Hampshire and northern New England, in terms, of the modem theory of drifting continents. Lyons started his New Hampshire field work - an extensive geological mapping program - in the Hanover area. In 1955, the results of his mapping of the Hanover quadrangle were published in the Geological Society of America Bulletin. Three years later the state published his map and an accompanying paper on the area. Since then, his New Hampshire work has been carried out in several parts of the state. He has been particularly interested in the chemistry and ages of emplacement of the numerous granite plutons (large igneous formations forced between layers) for which New Hampshire is famous, at least in geological circles. Using the decay of radioactive elements within the rocks as a tool, Lyons and his associates have quantified the ages of the granites and other rocks. This work has been of paramount importance in deciphering the events that led to the formation of the northern Appalachians. His sabbaticals since 1968 have been concentrated on research on the determination of ages of rocks at geochronological laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Arizona, and with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

His other major interest in New Hampshire geology has been the mapping of the structural relationships in south-central New Hampshire. This work has involved both original mapping and the remapping of a number of critical areas in this portion of the state. The culmination of Lyons' many years of work will appear in a new, reinterpreted geological map of New Hampshire, of which he is a principal co-author. The map will go to press in the next two years.

Although New Hampshire geology has been his first love, Lyons has pursued his scientific endeavors far beyond the borders of the Granite State. His doctoral dissertation and a subsequent scientific paper were on the Big Belt Range of Montana. Just prior to World War II, he spent a field season with the USGS in southeastern Alaska. Research contracts for the U.S. Air Force Cambridge Research Center and the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratories turned Lyons' focus to the examination of the physical properties of ice in the late fifties and early sixties. During this period he conducted field investigations of glacial and lake ice in Greenland and on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic.

In addition, Lyons has forged a reputation of excellence as a teacher, during his tenure at Dartmouth, supervising nearly 50 graduate theses and profoundly influencing the lives and careers of innumerable undergraduates.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

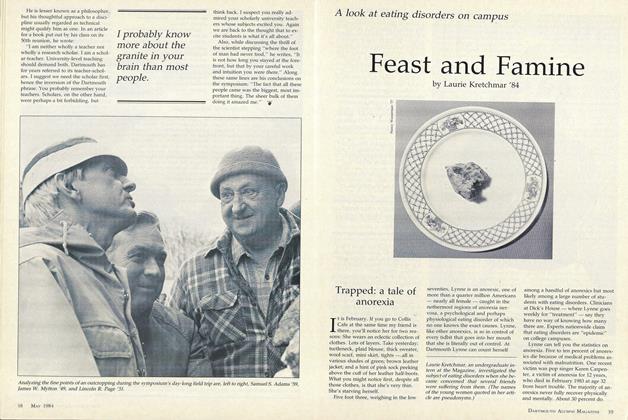

FeatureFeast and Famine

May 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Granite of New Hampshire

May 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

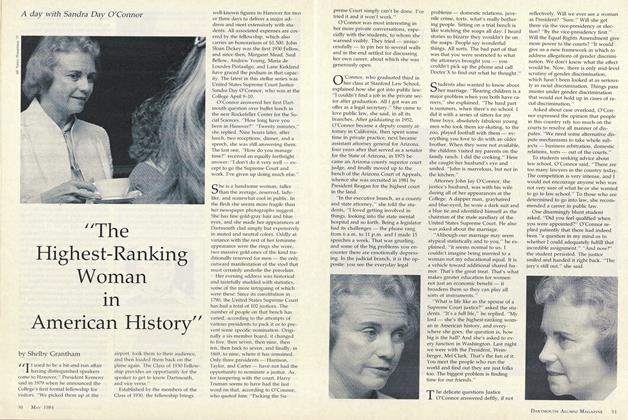

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

May 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

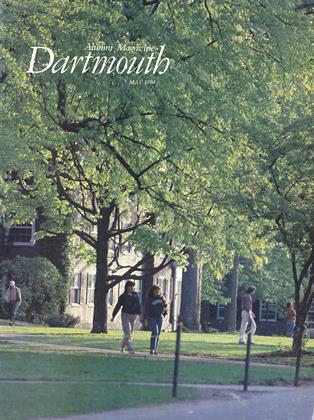

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Return to Dartmouth

May 1984 By Brian W. Ford '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

May 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

May 1984 By Clement B. Malin