A look at eating disorders on campus

Trapped: a tale of anorexia

It is February. If you go to Collis Cafe at the same time my friend is there, you'll notice her for two reasons: She wears an eclectic collection of clothes. Lots of layers. Take yesterday: turtleneck, plaid blouse, thick sweater, wool scarf, mini skirt, tights all in various shades of green; brown leather jacket; and a hint of pink sock peeking above the cuff of her leather half-boots. What you might notice first, despite all those clothes, is that she's very thin. She's starving herself.

Five foot three, weighing in the low seventies, Lynne is an anorexic, one of more than a quarter million Americans nearly all female caught in the nethermost regions of anorexia nervosa,a psychological and perhaps physiological eating disorder of which no one knows the exact causes. Lynne, like other anorexics, is so in control of every tidbit that goes into her mouth that she is literally out of control. At Dartmouth Lynne can count herself among a handful of anorexics but most likely among a large number of students with eating disorders. Clinicians at Dick's House where Lynne goes weekly for "treatment" say they have no way of knowing how many there are. Experts nationwide claim that eating disorders are "epidemic" on college campuses.

Lynne can tell you the statistics on anorexia. Five to ten percent of anorexics die because of medical problems associated with malnutrition. One recent victim was pop singer Karen Carpenter, a victim of anorexia for 12 years, who died in February 1983 at age 32 from heart trouble. The majority of anorexics never fully recover physically and mentally. About 30 percent do.

Lynne, who says she has anorexic "tendencies," will be the first to tell you her problem is a battle between the rational and the irrational. "I'm such a rational person. It's such a weird thing. I honestly don't understand why this happened to me." In the next breath she explains her current dilemma. She knows she needs to gain weight. "But on the other hand, you don't want to put on an ounce. Things get really out of perspective."

We have just finished eating dinner. Lynne ate a small salad with no dressing, croutons, or hard-boiled egg. She also had most of a small bawl of vegetable soup. "Right now I feel very bad," she says. "The vegetables had been soaking in broth." That makes them more caloric than they need to be, she means. If you remind her she needs to gain weight, she sighs and says, "I know; it's so hard."

If you were studying in Sanborn Tuesday night you might have noticed Jill. Five feet tall, dressed in gray flannel pants and a sweater, she cut a trim figure talking to old acquaintances. Jill is an '81; she works on Wall Street. She is a "recovered" anorexic who talks thoughtfully and somewhat bitterly of anorexia and her case history.

As a gymnast at Dartmouth Jill started a "rigorous" diet to lose about 10 pounds. "It worked ... it was wonderful," she recalls. "But all of a sudden it became a very meticulous calorie-counting diet." Jill dropped from a high of 125 to 98. "I just didn't stop," she recalls. When she went abroad to Europe on a language study program she was afraid that she might gain back the weight. Instead she lost 20 more pounds. "I can't tell you how I did it," she says. "I don't remember." When Jill got off the plane in Seattle, her mother was shocked. "She screeched at me and I hated her for it," Jill remembers. Her mother drove her to a pediatrician. "Psychologically, that's what I wanted to be treated as a little girl."

Jill says the "truth hit home" when she discovered that her best friend from high school was also anorexic. Until then Jill hadn't thought of herself as "too" thin. "Looking at her was like looking in the mirror," Jill says. "I feared for her life." Soon after that shock, Jill, under her pediatrician's supervision, began a slow weight gain.

"It's scary to know I could go to such extremes," Jill says. "I like to think of myself as a mature person. . . . The most basic thing to survival is eating — I somehow failed at that."

Jill claims that consciously or not, anorexics don't want to live. "Look at it," she says. "It's a slow painful suicide where you hope people will stop you. It's a real cry for help."

Both Lynne and Jill fit the perfectionist stereotype of an anorexic. Jill, for example, comes from a "super achieving, highly motivated, upper middle class, Jewish family." Jill says that until she came to Dartmouth she never had to make decisions on her own - but that the pressure to succeed intensified. Lynne comes from a rich, and rather formal, WASP-y family. She is a Rufus Choate scholar and has grades at the top of her class. She demands excellence from herself, studying all day long, not taking a break for hours at a time. What happens when her mind wanders? "I don't let it," she says firmly. Lynne says she feels no competition from others. Everything is self-induced. "I'm very happy if I get into a routine," she says. But in the next breath she adds, "you fall into ruts and can't break these patterns."

Talking with Lynne can be scary, for you begin to get a sense of the torment and loneliness she experiences every day. She explains that food scares her, that it makes her uneasy. "You set up rules for yourself. I do. If I break them I feel awful even though they're stupid." Why then does she make stringent rules to limit her foot intake drastically? "I don't know why but I do," she says. Jill describes this behavior as "an act of total control." Lynne's habits seem to prove that summation correct. For example, she permits herself to eat only half a muffin for breakfast. "But then it's really good and I eat it all and then I feel terrible," she says. Lynne does not eat again until dinnertime. It's as if she has a curfew that lets up around 6 p.m. "I starve myself during the day," she readily admits. "But I'm trying to reform and people don't realize that." A "huge" step for her is purchasing food, wrapping up a small piece of it to nibble on later, and discarding the rest. "At least I'm trying," Lynne says. "Now I feel guiltier about making rules than breaking them."

Flip through the pages of any magazine. There is no escaping the great emphasis on appearance and slenderness. Jill acknowledges this but says, "You shouldn't need to hurt yourself and others so deeply." She compares the evolving sickness of anorexia to alcoholism. "You can be a social drinker and then start drinking to solve your problems." People with anorexia become narcissistic, Jill admits. "It gives your whole life a real purpose, an identity. If you spend all your time thinking about eating and exercising, you don't have to worry about anything else." Anorexia also alienates its victims. "You just feel really alone," Lynne says. Part of the reason is that meals tend to be socially oriented and Lynne tends to exclude herself from that. She doesn't ever eat lunch or go to Thayer Dining Hall.

But part of the problem, she feels, is that people, specifically casual friends, have been avoiding her. She recently decided that their "hostility" might actually be uneasiness about how to deal with her thinness. In fact she didn't realize people were noticing until last week. "I didn't think people could tell," she confides. "I'm wearing at least three layers." However people have been noticing and some have been staying away from Lynne. "You get strange vibes from people but no direct communication," she says. "People won't go out with me. What do they think I'm going to do? Stab the waiter?"

Lynne refuses all invitations to eat meals prepared by friends. She wouldn't know the quantities or the ingredients. Could she just eat what she wanted and ignore the rest? "I

couldn't. It wouldn't go down my throat,"she says. She goes strictly to Collis Cafe. "I have this love/hate relationship with Collis," Lynne says. She points out that for people like herself, the lack of stability there is very frightening. "You don't know what the specials will be each day. They run out quickly. For me these things are a big deal." For her one true meal of the day "every calorie counts and you're not going to waste it at Thayer Dining Hall. The meal has got to be perfect. I want it to be good." ("Why," says Jill, when she hears about Lynne's expectations, "Why does it have to be perfect?")

Lynne's idea of an ideal meal would be a small piece of fish, a salad, and some vegetables. But, as she points out, that kind of meal is scarce in Hanover. Virtually every eating establishment in town focuses heavily on salads and desserts.

"I don't buy that argument," Jill says. "Anyone who wants a dinner can order a sandwich or a hamburger. She's making excuses. Ask Lynne why she doesn't eat enough to survive. No one did to me - but you can't do it like my mother did," Jill shakes her head. "I really wish I could say there was something someone could have done for me," she continues. "I can't help wondering if I had to have it. Maybe I needed that recovery and had to go through the disease first?"

Jill doesn't think that Dartmouth is "to blame" for her disease. But, she adds, problems can be compounded at the College. Similarly she doesn't think Dartmouth or the student counseling can do "a whole hell of a lot" for treating and overcoming anorexia.

Lynne seems to agree. She complains that clinicians at Dick's House are "nice" but don't offer any practical advice. She says students may be concerned for her but "Nobody ever comes to me." It bothers her that each time she goes to Dick's House she hears about two or three people who have expressed concern for her at the Dean's Office. "You just feel so helpless," Lynne says. "You got yourself into this. You have to get yourself out. I don't want attention. I just wouldn't mind a little support."

Innocent diets gone wild

"Theory is where everyone goes astray." So says Dr. Stan Fischman about the unknown origins of anorexia nervosa.

Dr. Fischman is an expert in treating anorexia. He was head of child psychiatry at Stanford University Children's Hospital from 1973 to 1976 and is clinical associate professor of child psychiatry at Stanford Medical School. He now works full-time in private practice in Mountain View, California.

He briefly explains the known facts about the disease before discussing the myriad theories and his own interpretations. People are considered "anorexic" when they lose 25 percent of their normal body weight and relentlessly pursue thinness. Almost paradoxically the majority of people who become anorexic start out weighing within 10 to 15 pounds of the average weight for their size. "They usually start out on an 'innocent' diet, most frequently between the ages of 10 to 21," Fischman explains. "Many of these patients are very athletic and in sports like gymnastics and track. Oftentimes they have coaches who emphasize thinness." Indeed, one recovered anorexic at Dartmouth remembers being told by her male cross-country ski coach in high school that she should be thin enough to stop menstruating.

Symptoms of anorexia include amenorrhea or loss of menstruation in women, hyperactivity, extreme sensitivity to cold, growth of very fine, dark hairs called languo all over the body, sudden swelling or bloating, skin that becomes pale and sometimes grayish, general fatigue, kidney failure, heart arrhythmia, and heart failure.

Another and very different sign of an orexia is a distorted body image. "Almost all of the patients see themselves as fat," says Fischman. "It's been well studied that the thinner they get, the fatter they seem to themselves." He recalls the 19-year-old Stanford patient who, at 68 pounds on her five foot six inch frame, looked emaciated. "One day when I walked into her hospital room she was standing in front of a mirror pinching what little skin she had left on her hips. 'Please doctor, if you'll just let me lose a few pounds, I'll be just fine, she said."

"Something goes wrong in their perceptions," Fischman says. "The vast majority feel like they're going to lose control if they stop the intensive dieting." Indeed, the statistics reveal this fear. Forty to sixty percent of anorexics do lose control over their self-imposed starvation. Some of them will become overweight when they ease up on their own stringent "rules." Others will control their weight by becoming bulimic, meaning they start a cycle of alternately gorging and purging themselves.

Anorexics become more and more isolated as they withdraw from people and social activities centering around food. Yet they are obsessed with the thought of food, calorie-counting, cooking, buying food, and reading recipes. Dr. Fischman agrees that these concerns affect almost everyone. "We're talking about a lot of normal stuff gone wild."

He notes that many anorexics claim they have an inability to eat: They complain that the food is "stuck" inside them. Recent studies have shown that the food anorexics eat is indeed not being properly digested. It appears that enzymes necessary for the digestive processes are not in some cases being manufactured properly - why is not yet known.

Finding causes to account for these symptoms is not easy. As Fischman says, there are many theories explaining anorexia. One holds that the victim is afraid to grow up. "If a person starves herself, signs of maturation go away," says Fischman. Then, he adds, "We're all afraid to grow up!" Another theory points to a symbiotic relationship between mother and daughter. In this theory an unhappy daughter may use dieting as a weapon against an overpowering mother. But "mothers," Fischman notes, "are often unfairly blamed in psychotherapy." Still another theory views the child as a symptom of deeper family problems. Perhaps the child is carrying the burden of the problems or is calling attention to the conflicts. On this Fischman says, "Read different family theorists and they'll give you different nuances."

A theory that Fischman takes more seriously is an old idea with new evidence. That is the physiological theory which maintains there is a biological relation between anorexia and chemical imbalances in the brain that confuse the patient and lead her to perceive that she is fat. It suggests that there is a genetic basis for this illness. Fischman adds that this information is "the latest dope" and 'probably won't be received very well in some places." Still, the theory sounds plausible to Fischman. Not only does it suggest genetic influences; it also takes account of the factor of cultural pressures. The theory speculates that certain people who are genetically susceptible to anorexia "cross the threshold" of "innocent dieting" in a society where thin is "in."

Further evidence for the physiological theory is the fact that many anorexics have a history of family depression, alcoholism and eating which may be genetically transmitted. "Something goes wrong in the brain, causing the chemical imbalances," Fischman explains. "Nobody knows where precisely. There is some basis for thinking the chemical imbalances can be attributed to a malfunction in the synapses, or nerve junctions." Particularly appealing, he says, is the hypothalamus which mediates many of the body functions that go awry in this illness.

Fischman thinks the causes of anorexia are largely physiological. "The reason is manifold. One, why, since 1965, is it suddenly coming back again? The rise has been exponential." Anorexia was first described in medical literature in the mid-1800s. While the disease was reported mainly among daughters of upper and upper middle class families, anorexia is now appearing in other parts of the socio-economic spectrum. Fischman cites changes in American standards of thinness so profound that such sex symbols of the fifties as Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell would be considered plump by today's standards. "In the mid-sixties along came Twiggy and Company" Fischman says. And with them, America's obsession with thinness.

Another reason Dr. Fischman endorses the physiological theory is that "everyone has virtually the same symptoms. That sounds more physiological than psychological." Nonetheless Fischman thinks that successful treatment of anorexia tries to "hit all the bases" in terms of theory.

Regardless of the various theories, Fischman warns, treatment is still long and difficult. The most severe

cases of anorexia require hospitalized treatment. One of the first steps for both the hospitalized and home patient is to regain weight slowly through renutrition. During this recovery period Fischman counsels patients about the physical changes their bodies are going through. "It helps to reduce the overwhelming anxiety that everyone with this disease has," he says.

He explains that many anorexics who stop their compulsive diets are scared by the changes in their bodies. Frequently they retain water and gain "false" or water weight. Other signs that scare them include a feeling that their stomachs look distended after they eat. Thus even anorexics who are seeking treatment are really "caught in a bind," says Fischman. "Everything they perceive is telling them what they fear: that they are getting uncontrollably fat." In addition to this counseling on physical changes, Fischman also suggests family or individual counseling and anti-depressant medication "when it's appropriate."

An important criterion for recovery, Fischman stresses, is the patient's willingness to recognize her illness and seek help. "I won't intervene with them until it's their choice - unless the illness is truly life-threatening," he says. "Anorexics become even better at deception if you try to coerce them into gaining weight."

What can friends do to help an anorexic? Fischman suggests expressing concern but not criticizing or cajoling an anorexic to eat. "Friends should at least recognize that she has a problem and offer support." He recalls the anorexic whose friends literally sat on her doorstep until she agreed to join them for meals and social events. Approvingly he notes the friends didn't try and make their friend eat; they simply saw to it that she came with them. That is the kind of support anorexics desperately need - the knowledge that people care, Fischman adds.

Compulsive eating

Katherine is a soft-spoken 30 year-old. She sounds thoughtful and sincere on the phone. You become convinced, talking with her, that she must have incredible resolve to have masked a painful secret for ten years. A bulimic, Katherine was a closet eater, binging and vomiting to control her weight. "I'd pretty much been getting increasingly out of control, to the point where I'd either fast or eat and then make myself throw up," she recalls. "I couldn't stop. I was suicidal. It's hard to analyze how it got that bad."

After seeking psychotherapy and behavior modification "That helped for a while, but the insight provided me with excuses for why I couldn't stop the compulsive behavior." - Katherine found fellowship in Overeaters Anonymous (OA), a group modeled after Alcoholics Anonymous, substituting food and hinging for alcohol. OA is a group that charges no membership fees and conducts no weighins. "Those of us who have had success take turns leading the meetings," Katherine explains. "We talk a lot about being people pleasers, about taking care of others. For example, instead of taking on anger, you direct it at yourself after everyone's gone to bed. You look for comfort in food."

As Katherine points out, it is considered "good and virtuous" in the American culture to be on a diet. "Women associate 'good' with carrots and 'bad' with ice cream and doughnuts," she says. "Eating becomes taboo. Binging and purging become a kind of cover-up for inner needs." In OA members learn to trust in themselves and realize they have the option whether or not to binge and purge.

Katherine does not consider OA a substitute for counseling. But, she says, it gave her the support she needed to change her behavior. "I lost the weight once I stopped dieting," she says. "I've maintained for two years. That's a miracle for someone who 'yoyoed' her whole adult life." Katherine now thinks of herself as abstinent. "I don't see bulimia as a curable problem, but it's one that I can control and live with."

She is worried about why more and more people seem to have eating disorders. "Is it due to more publicity, or is it because life is more complicated?" she wonders aloud. "Women ask themselves what they can control. It isn't their jobs or the world around them. It's their bodies," says Katherine.

"I hate to think I had to go through ten years of this. I think back to when I was in college. I wasn't ready to admit it was a serious problem. People didn't notice, but I was hoping someone would catch me. I really was." Katherine feels that friends who know must not pretend and go along with"the sham." As in dealing with an alcoholic, Katherine believes that friends should make it clear that compulsive overeating is "not an acceptable way to behave." She characterizes bulimia as a progressive problem until help is sought. Bulimics need to know they are not alone, she adds. "There is a way out."

Relief from the 'terrible secret'

How prevalent are anorexia and bulimia at Dartmouth? "I can't answer that," replies Diane Kilpatrick, Ph.D., a psychologist at Dick's House. She has been at Dartmouth since 1972, when the school went coeducational. "One, we don't know, and two, the issue is sort of like answering how many people are depressed or have considered suicide at Dartmouth." In other words, nobody really knows, and if anybody did, the information would be confidential.

"My hunch is that at any one time at the College maybe a fifth of the women are invested with a concern for body image. It's expressed in a variety of ways," she says, noting that young women tend to abuse food in much the same way as many men abuse alcohol.

"The reality is that there are individuals with a range of emotional disabilities who express eating disorders." Kilpatrick characterizes them as running the gamut from the person who fasts three days a week for weight control to the person who goes through periods of purging and exercising after heavy overeating. The group includes "the student who has developed such a pre-occupation with food that she could be characterized psychologically as anorexic." Bulimics binge and purge. Anorexics starve themselves. Quite often under similar circumstances.

"What we see predominantly at Dartmouth is women who start with a fad diet that gets out of hand in terms of habit arrangement," says Kilpatrick. Highly-motivated, success-oriented students, like the kind admitted to Dartmouth, are a target population for eating disorders.

Kilpatrick points out that the College, until recently, had not been very responsive to the needs of students in terms of eating options. "Dartmouth had a facility (Thayer Dining Hall) that was adequate for the needs of a homogeneous male population." But, she adds, "for a number of women, Thayer Dining Hall represents a frightening smorgasbord. Some of them feel more comfortable eating at Collis where their intake is more controlled." Kilpatrick has long believed that the College should offer other eating alternatives to a large cafeteria. She suggests having more kitchen facilities in the dormitories. (Now that Thayer Hall has undergone extensive renovation, Dartmouth students have more flexibility in the way of dining. They can purchase food by item as well as by meals.)

Though Kilpatrick is willing to describe the environment at Dartmouth surrounding eating disorders the target population and the shortcomings of dining options — she does not blame the College as the root of the problems. Rather she turns to several theories to help understand why so many women are afflicted with eating disorders. "Theories are useful to us in that they give meaning to our behavior, Kilpatrick says. She acknowledges the theories held by psychoanalysists, feminists, and behaviorists. She does not have much regard for the physiological theory that views anorexics as genetically pre-disposed candidates because of chemical imbalances in the brain. "It doesn't surprise me that it's offered as an explanation," she says. "There's an emphasis in biological science these days to emphasize the physical." She notes that anorexia does not appear in under-developed continents, like Africa. "That leaves open the question to me in thinking about anorexia as physiological," she says. Proponents of the physiological theory counter that candidates for anorexia "cross the threshold" in affluent societies emphasizing thinness.

Kilpatrick says her bias in terms of theory is that eating behavior has a developmental aspect with students. She believes that eating interacts at different stages with emotional, physical, and intellectual development. She notes that food, vital for survival, is often used as an outlet for stress. Simultaneously it can become a source of stress. As evidence of this developmental aspect to eating, Kilpatrick cites the support groups offered by Dick's House for students with eating disorders: These students range in age from 17 to 25. The issues for them, according to Kilpatrick, are different. What they have in common is an obsessed feeling that they are somehow inadequate in terms of body weight and a similar approach to dealing with that sense of inadequacy. The majority of Kilpatrick's patients with eating disorders are bulimic. They control their weight with binging and purging, by self-induced vomiting or laxatives.

In the past three years, the clinicians at Dick's House remember only one male student who came in because of an eating disorder. There are several explanations. One is the fact that societal pressures to be slim are much greater on women than they are on men. Another reason may be that men in weight-conscious sports, like lightweight crew, have coaches who are aware of potential problems. For example, Richard Grossman, coach for the Dartmouth men's lightweight teams, measures the body fat of lightweight aspirants with body calipers in January for a season that begins in April. "If someone needs to lose weight to meet the weight requirements but wouldn't be 'efficient' at that weight, we won't take him," he says. Those that are losing weight, he adds, are doing it for a stated purpose, not because of symptomatic deeper problems.

Along with the noticeable absence of men who go to Dick's House for help with eating disorders is the limited number of anorexics. "One of the very frustrating concerns for the mental health services," says Kilpatrick, "is that, by and large, anorexics don't seek psychiatric help." Those who do receive individual counseling. One junior who is anorexic explained that she was uninterested in discussing her problems with a group of bulimic women.

Even students who would like to join a support group can't simply "walk in off the streets"; they must first be interviewed to see if they have realistic expectations and "want more than a quick fix." Treatment of eating disorders at Dartmouth is especially difficult, notes Kilpatrick. "The idea of breaking a binging/purging pattern in one ten-week term is unrealistic," she says. "We're doing well if a person makes a commitment to being in a supportive group and is on campus two terms in a row."

The groups are kept small in order to use a cognitive or learned behavior approach. They use role-playing, problem-solving, time management, assertiveness, values clarification, and relaxation techniques to modify perfectionist tendencies. For some students, progress means finding out what their limits are. "If you've trained yourself to be the best you can be, you can impose a discipline that is boggling to those of us without it," says Kilpatrick. She explains that people with eating disorders must learn coping techniques other than narrowing their options, being "obsessive-compulsive," and "putting on blinders" to anything outside their spheres.

Kilpatrick suggests individual counseling or support groups for students at Dartmouth with eating disorders. The anorexic junior receiving individual counseling gives mixed reviews. "I don't know if it's really helping," she says. By contrast, the bulimic women who seek help in the support groups, says Kilpatrick, often feel relief that they are not alone: "Once they share the 'secret,' they find support," she says.

"These disorders are such that no one can help the victims but themselves," Kilpatrick says. Still, she notes, "peers can demonstrate the skills of friendship." One of the positive things about Dartmouth, Kilpatrick adds, is that here people perceive themselves as their brother's keeper. "Where people do a disservice in the guise of a friendship is trying to take over, assuming a nurturing role as a parent. That is not helpful at all. The individual must learn how to nurture herself." It can be very painful for friends, Kilpatrick says. "Some people respond by getting angry at the student with the disorder." But, she adds, "You can do nothing but be friends. Put yourself in her shoes."

Buxom Marilyn Monroe, considered plump by today's standards, was the feminineideal of the fifties.

At 91 pounds, five-foot-six-inch Lesley Hornby - better known as Twiggy"epitomized the sixties' thing for thinness.

Exercise queen Jane Fonda, who says she works out for hours each day, ushered in America's current craze for physical fitnessand strength in women.

"The most basic thing tosurvival is eating - I somehow failed at that."

"It's a slow, painfulsuicide where you hopepeople will stop you."

She explains that foodscares her; that it makesher uneasy.

"What do they think I'mgoing to do? Stab thewaiter?"

"The vast majority ofanorexics feel like they'regoing to lose control ifthey stop dieting."

"Anorexics become evenbetter at deception if youtry to coerce them intogaining weight."

It is considered "goodand virtuous" in theAmerican culture to beon a diet.

"What we see predominantly at Dartmouth iswomen who start with afad diet that gets out ofhand."

Highly motivated, success-oriented students— like the ones admitted toDartmouth — are a target population for eatingdisorders.

"One of the very frustrating concerns for themental health services isthat most anorexics don'tseek psychiatric help."

Only one male studentcame in because of aneating disorder.

"Where people do a disservice in the guise offriendship is assuming anurturing role as a parent. That is not helpfulat all. The individualmust learn to nurtureherself."

Laurie Kretchmar, an undergraduate intern at the Magazine, investigated thesubject of eating disorders when she became concerned that several friendswere suffering from them. (The namesof the young women quoted in her article are pseudonyms.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

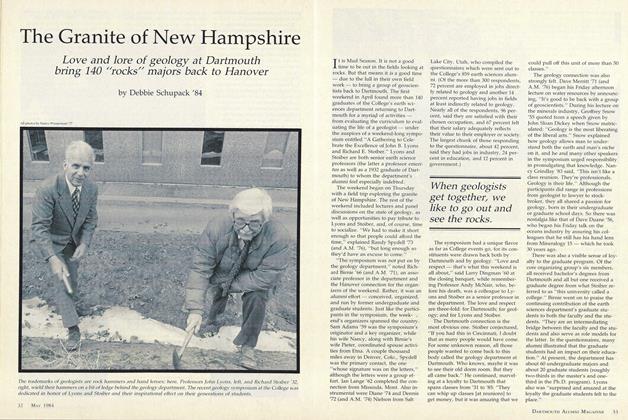

FeatureThe Granite of New Hampshire

May 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

May 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Return to Dartmouth

May 1984 By Brian W. Ford '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

May 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

May 1984 By Clement B. Malin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1984 By Burr Gray

Laurie Kretchmar '84

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Intern: Spying on the Real World

OCTOBER, 1908 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Article

ArticleFlamboyant Rabbi

DECEMBER 1983 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Article

ArticleOutward Bound for Outward Bound

DECEMBER 1983 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Article

ArticleAudacious Questions

MAY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Absolute and the Ambiguous

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHas America Neglected Her Creative Minority?

December 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTamara Northern

OCTOBER 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Rassias

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

APRIL 1992 By flagg Miller '91 -

Feature

FeatureSports for the Multitude

JUNE 1964 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Feature

FeatureHow Firm a Foundation?

By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS