The file for James Smith Rudolph '47 in the Alumni Records Office does not prepare one for dealing with a man who has been written up in many magazines and newspapers and interviewed by Susan Stamberg on National Public Radio's "All Things Considered." The only thing it contains beyond standard alumni questionnaires is a photograph of his 1965 receipt of the National Salesman of the Year award from Sonneborn Products Inc., a firm supplying chemicals to construction firms. The presentation came a little while before Jim Rudolph decided to quit a job that he had gone into because he had found it difficult to come up with a profession that matched his combination of qualifications a civil engineering degree from Dartmouth and a doctorate in French literature from the Sorbonne. Bored and unhappy in his work, he had sorted out his priorities, made a conscious choice about the kind of city he wanted to live in, and ended up owning two bookstores and an art dealership in Ann Arbor, Mich., a community he describes as a true university town: "It's so polemical it's sometimes hard to find two people who'll agree on whether it's a sunny day." It provides him, he says, with extraordinary resources for enjoying the good life.

This bit of background helps one to understand the current interest in Rudolph. He clearly has a penchant for lateral thinking and for the uncommon experience. (How many other Dartmouth alumni, one wonders, spent the first installment of their GI Bill grants on the purchase of a Matisse print?) The story of the paper clock fits right in.

Rudolph found the original version in a small bookshop in Paris in 1947 a booklet printed on thick paper containing 106 drawings which, when cut out, glued, and put together, made up the parts of a working clock. He spent the dozens of hours of careful, patient work that it took and was amazed to find that not only did the clock keep perfect time, but it even ticked. Determined to give them to all his friends, he went back to the store to buy up the remaining stock (which, to his dismay, he discovered consisted of but three copies) and to get information about the book's origins. Nothing useful was forthcoming: The book had been produced long before World War 11, nobody could track down any news of its creator or manufacturer, and not a single additional copy could be located.

For more than 30 years, the three precious copies went with Rudolph wherever his travels took him. "I couldn't think of a person in the world whose character, morals, and wit were so peerless that they deserved to own one of the last three extant examples of the best toy I'd ever seen in my life," he explains. But then, in August 1983, he read a brief note in the book trade column of The New YorkTimes Book Review describing how a book that could be turned into a paper model of the Empire State Building had surprised everyone by selling 100,000 copies. The next morning he was on the phone to New York publishers, and, against all the rules of the business, he got through to editors and other decision-makers through the simple procedure of telling whoever answered the phone that he had a brilliant idea to discuss and could not imagine that he/she would want to take the responsibility for depriving that publishing house of the chance to cash in on it. He used one of the aging surviving copies to make a new model, took it to New York to show to the most interested of the people he had talked with, and quickly found himself with seven firm offers to publish. The decision to go with Harper and Row stemmed from their telling him that Isaac Asimov a clock fanatic wanted to write the introduction. Rudolph translated the instructions from the original French, improved them, and arranged for the pieces to be redrawn. Make Your Own Working Paper Clock was born.

The rest is history or at least the beginning of another interesting chapter in Rudolph's life. The paper clock hasn't yet caught up with the sales of that Empire State Building book, but it's close to halfway. And presumably it will overtake it one day, because the result of all that painstaking work is so much more useful, portable, and attractive than a small-scale skyscraper. What pleases Rudolph at least as much as the windfall of royalties is the fact that he has received literally thousands of letters from people who have made the clock an unexpected reward for someone who calls himself an evangelist for his re-created toy. The fact is, of course, people aren't shelling out the dollars and putting in all that time because they need another timepiece. Quite apart from anything else, the dimensions of the paper cogs are necessarily very precise, and inevitably the moving parts lose their tolerance after very much use; so most people keep their clocks at rest most of the time, making them work only to impress their friends. What they are really buying, and then enjoying, is a link with the history of high-level tinkering, a chance to share in a small mystery, and a celebration of ingenuity of a most unusual kind.

Rudolph won't autograph copies of the book, being determined not to take more credit for it than is his due: "I'm totally incompetent to devise anything this complex," he says. "I only kept the original for 36 years." But the millions of enjoyable hours that have now been spent by those who have made their own paper clocks are due indisputably to Rudolph's flair and enterprise. The people who have this particular kind of time on their hands have good reason to be grateful to him. P.D.S.

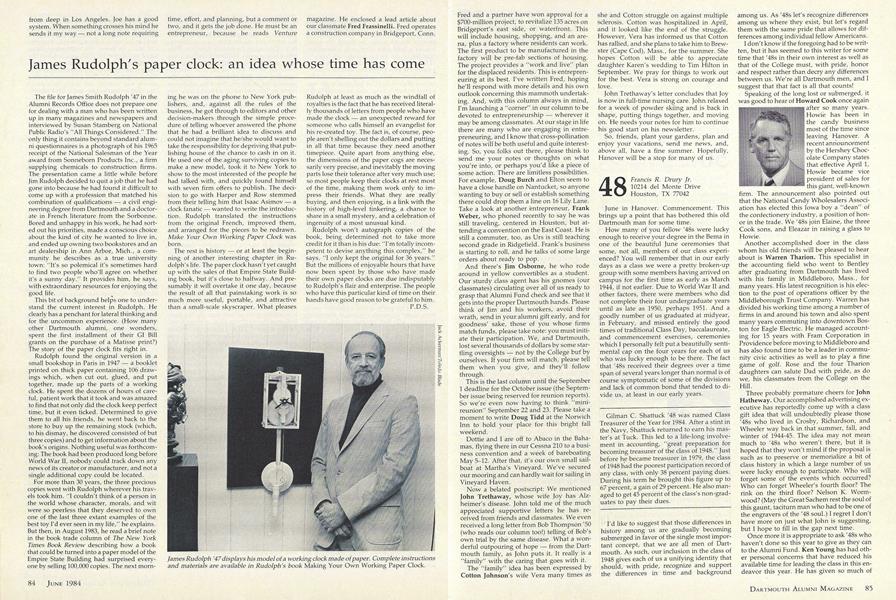

James Rudolph '47 displays his model of a working clock made of paper. Complete instructionsand materials are available in Rudolph's book Making Your Own Working Paper Clock.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor John Stearns '16: Rara Avis Una

June | July 1984 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

June | July 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

June | July 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureThe Best Part of My Academic Life Here

June | July 1984 -

Feature

FeatureMaking it Happen

June | July 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Feature

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

June | July 1984 By Young Dawkins '72