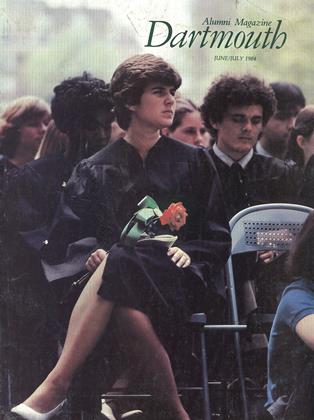

Class Day Oration, 1984

Dr. Harold L. Bond '42, who will be taking early retirement this year, has been teaching English at Dartmouth since 1947. He has served the College in many ways—as chairman of the English department, as the inaugural faculty director of the Dartmouth Institute, as faculty participant and director of the Alumni College, as the faculty representative on the Alumni Council, and, when he was a senior at the College, as president of the Dartmouth Outing Club. But most of all, he has served hundreds of students as teacher extraordinaire.

Some 20 years ago, one of those students, an apprehensive sophomore trying to decide whether to major in English, history, or art history, walked into Prof. Bond's Sanborn House office with a six-page paperon "The Concept of Hubris in Marlowe's Dr. Faustus." He wonderedwhether Prof. Bond would find the paper acceptable. (Just for the record, he did.) About a week before Class Day, 1984, Harry Bond sauntered up to the third floor of the old Crosby House to the Alumni Magazine office suite with an untitled, four-page paper in hand. Knowing what kind of lecturer he was and also that the Class of 1984 hadinvited him to give their Class Day Oration, I asked Prof. Bond (I stillcan't call him "Harry") if we might consider it for publication in thesepages. He was worried that it might not be quite suitable. Shakespeare's "The wheel is come full circle," echoed in my mind. Appropriate, that, Ithought. And it goes without saying that we are very pleased to beprin ting it h ere. D.M.G.

Mr. President, Guests, and Fellow Students:

We meet today in the Bema for two reasons: one is to celebrate the Class of 1984. The other is to prepare in our own way to say farewell for a while to Dartmouth, you after four years, I after 46 years. I say "for a while" because I know you'll be back.

We have already had celebrations of 1984, and I want to add to them by saying that it has been a privilege to share with many of you a reading of some wonderful literature, most particularly Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, and the other romantics, and also the writers and translators of the King James Bible. Moreover, the best part of my academic life here has been the association with students. I am always astonished by their energy, vitality, talent, and sometimes their brains, and also by their remarkable diversity. I see before me artists and poets, champion skiers and outstanding athletes, playwrights and novelists, birdwatchers and hikers, physicists and geologists, candidates for leadership in law and business, men and women who will grace the professions, men and women who have become and will continue to be part of the Dartmouth family.

It is fitting, too, that we meet in the Bema. This amphitheatre was constructed 102 years ago. The seniors in the class of 1882 wanted a private place for their class day celebrations. Ever since that year, Class Day has been held here (weather permitting), and for a great many years the commencement ceremony, too. Commencement was moved to the lawn of Baker Library in 1953 when President Eisenhower received an honorary degree. The crowd of 10,000 people could not be accomodated here; but Class Day has remained in the Bema with its lovely trees, the New Hampshire granite, the glorious sunshine, reminding us of the wilderness from which the College grew.

The word Bema comes to us like many good things in our civilization from ancient Athens. Literally meaning a step, it was the speaker's platform from which statesmen addressed the Athenian Assembly. Since then the word has been used to designate the platform from which services are conducted in a synagogue, and, in the Greek Orthodox Church, the enclosed area about the altar. The connotations of something sacred in the term have remained; and, if you won't mock at my thought in an age when it is pretty hard to say that anything is sacred, our Bema is Dartmouth's sanctuary. D. H. Lawrence, when visiting the great Benedictine Abbey at Monte Cassino in Italy, said that it was one of the quick spots of the earth-living, energizing, vital throughout the millennia. The Bema, too, is one of the quick spots of the earth, even though Dartmouth has only a little over 200 years of history.

Yet, in reality, our roots go back much further than 200 years. Like the andrake, a symbol of fertility and creativity, we have two great taproots for our College, roots which started growing over 2,500 years ago, one in Athens and one in Jerusalem. And in our time, when all we hear is talk about change, accelerating obsolescence, the value of innovation (always assumed to be good), it does not hurt to recall that important things do not change, things like love and hate, freedom and tyranny, peace and war, life and death, and things like our roots.

When Eleazar Wheelock selected Vox Clamantis in Deserto as the motto for his college, he almost certainly was thinking of the real wilderness that was this country in 1769. But the motto has much more to do with truth than with wilderness; and the term which was once relevant to uncultivated and unsettled parts of the earth, almost from the beginning had the metaphorical meaning of what Dante, Spenser, Milton, and Bunyan would call the wilderness of the unenlightened world. The whole verse in Isaiah 40, from which the motto is taken, reads (in the King James English):

The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

The voice speaks through the prophet to a people in slavery by the rivers of Babylon where they had been in captivity for 50 years. It comes at the beginning of what was to become another exodus. Just as Moses led the chosen people out of slavery in Egypt, so the Lord will lead his people back to the Promised Land. "The Lord will come with a strong hand, and his arm shall rule for him. ..."

And he shall feed his flock like a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs with his arm, and carry them in his bosom, and shall gently lead those that are with young.

From slavery to freedom with "the word of our God [which] shall stand forever," this faith almost certainly was the foundation of our College.

To turn briefly to our other root, and the second Bible of Western civilization (I mean the literature of classical Greece), we might mention only the great oration by Pericles at the Bema in Athens at the end of the first year of the Peloponnesian War. He spoke proudly of the ideals of the Athenian state; and although Athens was to lose this terrible war, she won the honor of becoming one of the major civilizing forces of the Western world. Here are some of the ideals. They lie behind not only the foundation and purpose of our College, but also behind the birth of the United States:

Our administration favors the many instead of the few; that is why it is called a democracy. Our laws afford equal justice to all. . . . Advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merrit. We cultivate refinement without extravagance, knowledge without ostentation; wealth we employ more for use than for show. . . . Our ordinary citizens, though occupied with pursuits of industry, are still fair judges of public matters. ... Instead of looking on discussion as a stumbling block in the way of action, we think it an indispensible preliminary to any wise action at all. . . .

Well, these ideals and this faith are in our roots, and they provide rich

nourishment even to this very moment. I have said that the important things do not change, but the surface of our lives is always changing. And so it is with Dartmouth. If my ancestor, William Bond of the Class of 1812, could return to Hanover today, he would recognize virtually nothing on the campus But our activity, described by some as the pursuit of truth among friends, he would recognize; and he would not have any trouble meeting his old friends on the shelves of our library.

Yet one serious worry I have about the future here and elsewhere in this mechanized, computerized, nuclear world is that surface change may become so great as to render us unfit or unable to read the great books, and to partake of the great tradition of a truly human life and spiritual health. You will remember that citizens of Huxley's Brave New World were unable to read the classics. When they tried to read of the love of Romeo and Juliet, they burst out in uncontrollable laughter. Well, to make no greater claim, graduates of Dartmouth can still read Shakespeare, and we even ask our freshmen to try Paradise Lost.

Let me conclude by remembering my own commencement here in the Bema, 42 years ago. Pearl Harbor struck us in our senior year, and a campus that was largely pacifist knew overnight that it had to go to war. Spring break was cancelled and Commencement was moved forward one month to May 10th, to enable us to join the services all the sooner. From here we did indeed go 'round the girdled earth: England, North Africa, Italy, France, Burma, the Philippines, Guadalcanal, Okinawa, and many other places. Forty years ago last Monday, I was riding in a jeep behind the leading tank in the American and British taking of Rome; and 40 years ago last Wednesday, American forces with Dartmouth men among them stumbled ashore in the bloody landings at Normandy. Thirtythree members of my class did not return from that war. The president of our class was last seen diving his at tack-plane on a Japanese battleship. Another member of the class whom I

once watched schuss the headwall at Tuckerman's Ravine, lost his life in the mountains of northern Italy. But all of us were better able to do what we had to do in those years, and even more importantly in the years of peace that followed, by what we gained from Dartmouth. We took with us the memory of Dartmouth's sharp and misty mornings, The clanging bells, the crunch of feet on snow, Her sparkling noons, the crowding into Commons, The long white afternoons, the twilight glow. . . . We took all this, but even more, the voice that we heard then and still hear now, crying in the wilderness. It is still a guide.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor John Stearns '16: Rara Avis Una

June | July 1984 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

June | July 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

June | July 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureMaking it Happen

June | July 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Feature

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

June | July 1984 By Young Dawkins '72 -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

June | July 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryGoing Places

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May/June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

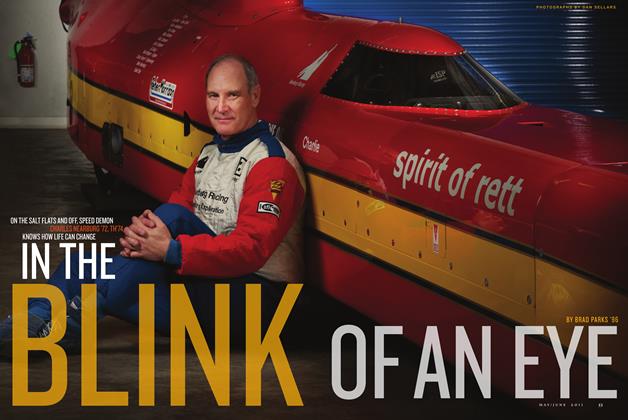

FeatureIn the Blink of an Eye

May/June 2011 By BRAD PARKS '96 -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

JULY 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureMcLaughry Closes 14-Year Regime As Dartmouth's Head Football Coach

January 1955 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham