Some alumni and emeriti faculty will remember John Barker Stearns '16. He had a long, distinguished teaching career at Dartmouth, retiring as Daniel Webster Professor and Professor of Latin Language and Literature. But John was more than a professor of Latin. He taught art, archeology, and classical civilization, which, to the uninitiated, was ancient history. Lucky, indeed, were those privileged to have had one or more classes with him.

I first got acquainted with John in 1932 when I took his "Classy-Civ" course on Rome. Fortunately it was taught in English. I was fascinated by Rome, even though after five years of high school Latin, I had barely progressed in ability to translate beyond "Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres." I immediately became an admirer.

Not only did John know his stuff, which he enthusiastically imparted to his students, he looked like a stereotypical Roman senator. Tall over six feet and with flowing white hair and a ruddy complexion, John exuded a dignity that camouflaged his puckish humor, particularly his unabashed patriotism, glimpses of which sometimes flashed in the classroom.

The first inkling of this aspect came when the Japanese invasion of Manchuria hit the headlines. As we settled in our seats, the professor looked the class over, assured himself that we were awake, and then addressed us.

"Gentlemen," he said. "Today we were going to discuss the influence of the geography of Italy on the Etruscans and their relations with the Romans. But fighting is accelerating in the Far East, and all signs indicate it will not be long before the world is once again at war. It seems to me it is essential for you to be ready for it. For we shall be in if. You will be in it.

"Never mind the protestations that 'We shall never fight/ which some of you have been making along with students in other colleges. War is coming and it is far more important that you be prepared for the challenge than spend time on the Etruscans, as important to history as those people were. I suggest, therefore, that we retire to the lawn of Carpenter (which then housed the classics department) where I will teach you the Manual of Arms. To be sure, my version will be World War I vintage, which I daresay has been changed, but it will at least give you a leg up."

While we did not go down to the lawn, the discussion that morning had absolutely nothing to do with Etruscans, Rome, or Italy. But it was the first revelation to me that John had been involved in "The Great War," which later on explained a number of John's peccadillos, so amusing to his friends, albeit not always understood or appreciated by those who did not know him.

John was a rock-ribbed Yankee. When and how he got his interest in classical languages, the life and culture of Rome, Greece, and the Middle East, remain unrevealed to me; only the bare bones of his earlier life are documented in the College archives.

Born in Norway, Maine how much more Yankee can you get? somehow he found his way to Dartmouth in 1912. Latin or Greek was then a required subject for both admission to the College and for the A.B. degree. Whether some teacher inspired that stripling from "the land of the spruce and the hemlock," or whether he came from parents who revered the classics, is immaterial. John was hooked on ancient cultures.

After Dartmouth, from which he was graduated with a Phi Beta Kappa key, he received his A.M. from Princeton in 1917. World War I interrupted his immersion in the literature, politics, sociology, military ventures, and culture of our Mediterranean forebears. He joined the United States Army Ambulance Service and went overseas in the American Expeditionary Force as a first lieutenant. After the war he returned to Princeton as an Instructor; picked up his Ph.D. in 1924; taught a couple of years at Alfred University; and joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1927 where he spent the rest of his life.

Although I crossed paths with John occasionally as a student after finishing his course, it was not until I joined the College staff in 1936 that I began to know him more intimately. College personnel saw each other more frequently in those days, for Hanover was a very small town. Furthermore, I got to know a number of people who had known John Stearns a lot longer than I had. Kay and Bob McKennan '25, for example, were my next door neighbors (she, the daughter of my Dean, Craven Laycock '96, and Bob, a professor of anthropology). As the new tenant in the apartment the Stearnses had just vacated, I heard a number of stories about John Stearns from the McKennans.

One day I mentioned to them that I had never seen John drive his automobile, that his wife, Elsie, seemed to chauffeur him everywhere. They told me that was correct John never drove. He did not have a license. In fact, they recounted, he had never driven since World War I. It seems John had made a vow, and being a man of the old school, he believed in keeping his vows. The genesis of that vow involved drinking and driving, which suggests that this is not a new problem.

One stormy night on the front, Lt. Stearns and his companion ambulance driver sought shelter from the rain in what appeared to be a decrepit, abandoned shed. Eureka! Poking around in the cobwebs and debris to arrange reasonably comfortable squatter's accommodations they discovered a goodly supply of brandy.

Since they were not at the moment encumbered by their usual mission of transporting the wounded to field hospitals, and recognizing their opportunity to become heroes with their buddies, they highjacked as much as they could load into their ambulance. And, as was only natural, they decided to sample the product to test its quality. Not being assured of the reliability of their palates as testing devices, they continued their research with unflagging persistance before and during their resumption of movement back to the base which, considering the circumstances, they believed was prudent even though it was still dark and raining.

Come the dawn. Christ! They were lost. In fact, it was quite clear from all the evidence that they were behind enemy lines. That sobered them up pronto.

Hiding their vehicle as best they could in some brush, praying, and abstaining from sustenance of the liquid kind, they luckily remained undiscovered for the remainder of the day and when dark descended managed to find their way back to their side of the front.

During the obviously anxious and perilous hours, John decided to forget the lares and penates to whom he usually turned for supplication and vowed that if they survived the mess they were in and safely made it back to the good ole US of A, he would never drive an automobile again. He never did.

It was typical of John, as compared to what "normal" folks might have done, that he eschewed driving. Most people would have sworn off drinking.

Some twenty years or so after that event a couple of our mutual friends, namely Professor Donald Bartlett '24 and Assistant Dean of Freshmen Charles Dean Chamberlin '26, discovered that John had idiosyncracies other than not driving an automobile.

John was firmly convinced and most disappointed that Americans did not fully appreciate the deeper significance of their freedom and especially of their birthright. In short, while firecrackers and noise were enthusiastically endorsed as part of the birthday party, John felt that more serious obeisance should be paid to the nation's founding. Accordingly, it had been his custom for a number of years on Fourth of July to rise at dawn, step into his yard formally dressed in striped pants, swallowtail coat, foulard tie, grey gloves, and a tall silk hat; then to set up a soapbox carefully preserved for the purpose, stand on it, fire a doublebarrelled shotgun into the air, and read the Declaration of Independence.

It was revealed by no less a person than John's wife, Elsie, that John felt deeply the apparent lack of appreciation of this ceremony because year after year his only visible audience was a melange of neighborhood dogs, pigeons, and an occasional six-year-old up early with his torpedoes but too young to understand the deeper meanings of what he had heard. However, John was gratified at the scientific reconfirmation of Pavlov's theories to hear each time the voice of one neighbor who lived just up the hill, Mrs. Hazelton, wife of Sydney C. '09 (swimming and assistant football coach). Mrs. Hazleton's bedroom window was open (it was July), and John would chuckle to himself as he heard her annual complaint to Sid: "There goes that goddamned fool again."

Three of us, Bartlett and the two Chamberl(a)ins, formed a committee to see what could be done to rectify the deplorable audience for John Stearns's oratory. After several meetings and some research, a plan emerged. The Stearnses had recently moved to River Ridge, a somewhat more ostentatious neighborhood than Valley Road, their former locale. Reconnaissance revealed a good-sized house, at the rear of which was a driveway leading to a garage in the cellar but protected by a sizable lot of pine trees and shrubbery: excellent cover for the mission.

Dean Bartlett (as he was called by title and name), had a yacht-race starter cannon which fired blank shotgun shells. That would take care of the opening salvo, but how to continue an appropriate barrage without undue delay for reloading was a challenge. Someone recalled that John had admirers and friends throughout the community, not the least of whom were the two senior painters on the College's buildings and grounds crew. These were the brothers Grant, Ora and Ira, who had a fife and drum corps of six or eight natives and gladly served various causes in the area.

Delighted to be asked to join the expedition, the Grants accepted the invitation, provided they would be released in time to make the Union Village parade to which they were annually committed and which, they informed us, John had for years attended as a spectator jointly in their honor and that of the occasion.

D-Day was, of course, the Fourth; ElHour, zero four hundred. And, to avoid any possible imposition on the lady of the house should she be impelled by her innate and gracious hospitality to provide catering services to hungry troops, it was decided that the invaders would bring with them sterno stoves, frying pans, coffee pots, and ingredients such as bacon, eggs, and coffee for a morning picnic in John's backyard.

Amazingly, the task force arrived on time and set up shop by the garage door with minimum noise. Not a creature was stirring. Not even the earliest of birds was chirping. "Fire when ready, Chamberlin."

"BLAM" went the cannon. "Tweetyde-tweety-de tweet" went the fifes. "Rrrumbeldy, rrrumbeldy, rrrumbeldy" went the snare drums. "Boom, boom, boom" went the bass drum which was beaten with eclat by Ory's wife, a large, vibrant and enthusiastic New Hampshire woman.

Well! That woke up the neighborhood. As Yankee Doodle echoed off the hills and homes of the valley the dawn's grey loom began to creep over the edges of Balch Hill and Velvet Rocks. People could recognize each other even in the shadow of John's pines. Windows could be heard opening in adjacent houses, along with expletives.

Elsie stuck her head out of a window above the assemblage and the serenade was silenced for a moment. She was obviously finding it difficult to speak. She simply said, "As soon as John can compose himself and get dressed, he'll be down."

The invaders renewed their tweeting, booming, and blamming.

A sign on the garage door indicated that John had anticipated neighborly visits throughout the day though not, as was readily evident, for his annual dawn rite. Large arrows painted below the legends "Fireworks" and "Firewater" were proof that appropriate supplies lay within.

Two other objects foreign to the environs were flags we had carried along to lend authenticity to the affair: one an American flag, and the other a Confederate flag.

Why the Confederate flag? No one, not excepting her husband, ever really knew. It was brought by Don Bartlett's lovely wife, Henrietta. "Henry," a southerner of antebellum ancestry, thought she should contribute something other than breakfast and had sat up the night before cutting and sewing the flag. After all, in 1776, men from the colonies which later were part of the Confederacy had signed the Declaration. Why not a flag?

But Henry had had a problem. She did not know how to make a fivepointed star. Her flag was graced with six-pointed stars. But no matter. By the time John had dressed and reached the parade ground, he had an audience which was larger than pigeons, dogs and one six-year-old kid. He had the "invaders," whose cacophony of cannon fire, fife toots, and drum beats continued unabated.

In addition, during the enrobing interval, Caryl Francis "Pat" Holbrook '20, assistant football coach, former A.E.F. soldier, and John's nearest neighbor, came trotting over shooting a cowboy six-shooter. Dick Goddard '20, professor of astronomy and an exWW I Navy ensign, ambled, as was his wont, down the street to see what the hubbub was all about. Schuyler Berry, a local mailman who lived across the hollow from John, came running through his cornfield waving a white sheet on a long pole to indicate his surrender. Others of all ages gradually gathered in various stages of wakefulness and ablutions.

John appeared impeccably dressed in full uniform. The soapbox was placed, the shotgun fired, and the Declaration of Independence read to admiring attention. Then John opened his garage.

The kids turned to the fireworks and soft drinks, which had not been advertised; the adults to the firewater. The initial invaders started their sterno stoves and the aroma of frying bacon infiltrated the air, already sweetened by the pines and flowers of John's backyard. These enchanting olfactory sensations were only slightly tainted by the odor of burnt gunpowder.

By seven o'clock not only was the Grant Fife and Drum Corps well-fortified from the available supplies, half the neighborhood wanted to bang the bass drum. A few got the opportunity whenever Mrs. Grant had business in the garage, and in the process, several new facets of John's personality were gradually revealed.

First, John's backyard was woven with carefully laid-out pathways and every flower, bush and tree was labelled in Latin.

Second, a large array of tools hung ever so neatly on the walls of John's garage, and the handle of every one was painted bright red. Upon inquiry regarding this rather unusual expenditure of energy, not to mention paint, John explained.

"Simple," he said. "When one of my neighbors borrows one of my tools he can hardly forget where it came from. If he does, I can see it whenever he uses it and remind him."

Third, John was a key collector. As one wended his or her way to the bar in the garage, there, staring him in the face was a large, heavily constructed closet whose door was surrounded by at least 2000 keys, each hanging on its own nail. The door to the closet was locked.

"What the hell is all this, John?"

He laughed. "Elsie's family had an interest in a trans-ocean liner and when they put it out of commission, she acquired a portion of its liquor. It's all stored in that closet."

"But why the keys?"

"Oh, just to have some fun. When my American Legion group meets at my house, which they do about once a month, I give them a drink or two after the formalities. Sort of loosens up the party. Also, to encourage attendance, I have promised that if anyone can find the key which opens the door I'll give him a bottle of his choice. That gives them something to do before they go home."

"Has anyone ever found the right key?"

"Think I'm stupid? I keep it right here in my pocket," upon which he fished it out and restocked the "firewater" table.

Along about nine o'clock the Fife and Drum Corps had to leave for their commitment in Union Village. John felt obliged to go too and changed to less formal clothes. His largesse of fireworks and firewater was temporarily depleted pending his return.

The "invaders" were invited to tag along, leaving their impedimenta at John's house to be picked up later. They accepted the invitation as did a number of the other "guests." The Union Village Fourth of July parade thereby virtually doubled its usual number of spectators.

As we were about to depart the Stearns premises, another of John's neighbors, Jim McCallum, English professor and author of several Dartmouth historical volumes, a World War I USN veteran, and although somewhat dour as a good Scotsman should be, a superb teacher, rode past the house on his way to get his newspaper uptown at Dave Storr's bookstore. He did not deign to glance at, much less recognize, the assemblage.

John chortled. "That proves this party was a great success," he said. "Jim is mad. We woke him up. He won't speak to me for a month."

The Union Village parade was composed of the Grant Fife and Drum Corps leading, followed by a fire engine from Hartford, Vermont, a Grange float, four or five veterans from World War I, and the Spanish-American War in their respective uniforms, one member of the Grand Army of the Republic riding in a Model T Ford, small troops of Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts and, bringing up the rear, a man in a horse and buggy decorated with red, white, and blue crepe paper streamers. The parade wended its way down the hundred-yard stretch of Main Street, turned and returned to its starting point. Everyone stayed until the parade was over, and no one, except perhaps two or three people in the Stearns group, noticed a slight wobbling in the steps of the Grant bass-drummer. The throng dispersed.

The clean-up in the Stearns backyard was expedited by "one more for the road." Then John said he hoped that next year we could hire a hayrack and take the show all over town. His motion was unanimously adopted.

Came next year: Chamberlin was in the Army, Bartlett and Chamberlain in the Navy. Stearns and Goddard were trying to help train Dartmouth V-12 students to be officers in a war for which these professors were this time too old to wear a uniform. The reading of the Declaration of Independence in John Stearns's backyard became, along with Cicero's orations, ancient history. One or two of us recalled John's prediction of 1932.

About 25 years later it was clear that John Stearns was still John Stearns.

For some unrecalled reason, I was honored with an invitation to attend a luncheon at the fiftieth reunion of the Class of 1916. And being smart as some reuning classes are they had name tags large enough to have lettering at least an inch tall; the names could be read by most at a distance of 20 feet.

I saw John and went to shake his hand, only to see his tag sporting the legend, "Spike Stearns."

"John," I said. "I never knew you were called 'Spike.' "

"I never was," he said. "I'm just finding out which of my classmates really knows me."

I wonder how many really did.

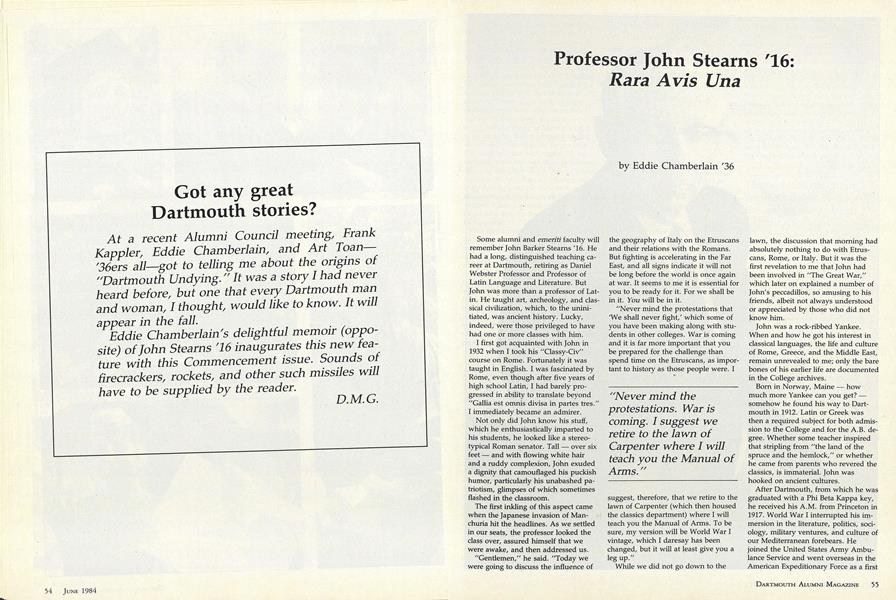

On stage in one of Dartmouth's most historic commencements, John Stearns (fourth from left) looks on as John SloanDickey '29 gently chides Sherman Adams '20. To the left are lester Pearson of Canada, and the featured speaker, PresidentDwight D. Eisenhower.

An Alumni Award at his 50th reunion was cause for a smile by recipient Steams, left, as well as by donor Francis Childs '06.

To call the author of this article a bitof a character himself might be considered an understatement by those whoknow him well. Eddie has stories andstories and then some. He has been inHanover, with time out for World WarII, ever since he arrived on the Plain in1933 during the Depression. Duringthe fall of his freshman year, Eddieplayed a large part in nixing what hadcome to be known as "the Yale Jinx"with his brilliant play on the gridiron.During his tenure as director of admissions, he made — by his own admission a few mistakes, letting in a fewof us who, but for the grace of Godand Chamberlain, might well be toilingin other climes. D.M.G.

"Never mind theprotestations: War iscoming. I suggest weretire to the lawn ofCarpenter where I willteach you the Manual ofArms.

It was typical of Johnthat he escheweddriving. Most peoplewould have sworn offdrinking.

It had been his customon the Fourth of July torise at dawn, step intohis yard formally dressedin striped pants and silkhat, fire a shotgun intothe air, and read theDeclaration ofIndependence.

Through his neighbor'swindow could be heardthe annual complaint:"There goes thatgoddamned fool again."

D-Day was the Fourth;H-Hour was zero fourhundred. 'Fire whenready, Chamberlin."

John had anticipatedneighborly visits, thoughnot, as was readilyevident, For his annualdawn rite.

He had the "invaders"whose cacophony ofcannon fire, fife toots,and drum beatscontinued unabated.

John said he hoped nextyear we could hire ahayrack and take theshow all over town. Hismotion was unanimouslyadopted.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

June | July 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

June | July 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureThe Best Part of My Academic Life Here

June | July 1984 -

Feature

FeatureMaking it Happen

June | July 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Feature

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

June | July 1984 By Young Dawkins '72 -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

June | July 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Eddie Chamberlain '36

Features

-

Feature

FeatureGuy P. Wallick '21 to Head Alumni Council for 1957-58

July 1957 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPipes's Cinch

MARCH 1995 By Al Henning '77 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2013 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

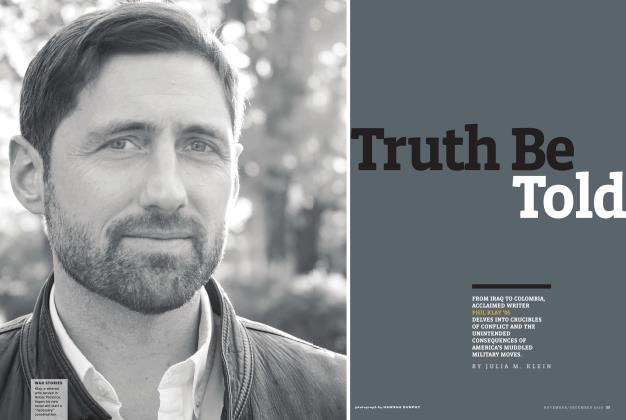

FeatureTruth Be Told

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Cover Story

Cover Story"The Art of Making Things Right"

September 1986 By PETER J. ROBBIE '69 -

Feature

FeatureShrink Rap

NOVEMBER 1990 By Rob Eshman '82