Accompanying illustrations taken from Herrad von Landsberg's Rose of Learning.

In the Middle Ages, nearly everyone knew at least three things about the world: that it was old; that it was flawed; and that it was headed for disaster. As a result, attitudes then may initially seem to resemble attitudes now, but investigation soon brings sharp differences to light, among them the fact that few medieval observers found this knowledge distressing. In 601, for example, Pope Gregory the Great wrote as follows to a recent English convert, King Ethelbert of Kent: We would have your glory know that . . . the kingdom of the saints is about to come . . . Many things are at hand which were not before, among them changes of air; terrors from heaven; tempests out of the order of the seasons; earthquakes in several places; wars, famines, and plagues ... If, therefore, you find any of these things happening in your country, let not your mind be in any way disturbed. For these are but signs of the end of the world.

In so writing, Gregory demonstrates that his differences from the twentieth century result from something more than enthusiasm for impending doom. Rather, he displays a confidence in the meaning and accuracy of his data that far exceeds that of modern research. There is, however, an easy explanation. If the pope knew that the end was near, this was because (as he assured the king) his information had come from "Holy Scripture, from the words of the Almighty Lord." In fact, if we are to believe the symbolism of a portrait in the Registrum Gregorii, a late tenth-century manuscript, this last of the Church Fathers may have been overly modest about the sources of his learning. For in that picture Gregory sits at his lectern, Bible at hand, but at the same time the dove of the Holy Spirit rests lightly on his shoulder, both guiding his interpretation and supplementing it with further truths.

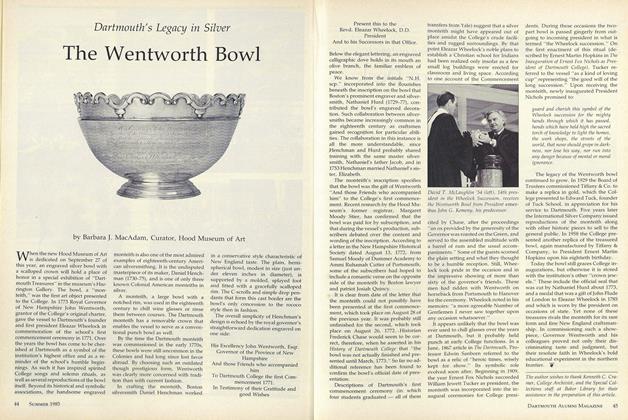

If such religious values have little to do with education and knowledge as most moderns would define them, the fact is that most people in the Middle Ages thought of them as little more than an articulated version of the divine wisdom displayed in the Registrum Gregorii. In the late twelfth century, for example, an abbess named Herrad von Landsberg composed a Hortus Deliciarum or "Garden of Delights" for the edification of her nuns, its principal illustration being a rose of learning, in which a personified Philosophy sits enthroned and attended by Socrates and Plato. Surrounding that trinity are the rose petals of the seven liberal arts themselves: the grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic of the basic trivium; and then the music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy of the more advanced quadrivium. Without a doubt, this rose of learning lay at the very heart of Herrad's educational delights.

At the same time, though, Herrad's garden, like Eden, was not without its dangers. For, outside and below the rose's circle of perfection, four figures are shown. Like Gregory the Great, they sit with books at their lecterns, and also like Gregory they have birds on their shoulders. Obviously, though, these nervous and scraggly creatures are no doves of the Holy Spirit. On the contrary, to judge from the inky blackness with which Herrad has portrayed them, they must be the messengers of Satan himself. And as for the men shown receiving the demonic word, these Herrad labels Poete vel Magi, a turn of phrase which can be translated, under the circumstances, only as "Poets or Eggheads."

Although the poetic muse would thus appear to have brought the abbess little delight, the precise reasons for her disapproval remain obscure. Is the picture to be taken literally? If so, poets and poetry must be bad largely because they have no recognized place within the charmed circle of the liberal arts. Yet it could also be, surely, that Herrad's condemnation reflects Plato's conviction that poetry represents only the emotions - and hence should be seen as a mere perversion of those arts. Given the ambiguity of the evidence, perhaps the only safe" conclusion is that, whatever the specifics, the modern observer is here being confronted with one of education's first battles over the curriculum and the ever-vexing question of which subjects to recognize as truly belonging to the liberal arts.

Perhaps needless to say, these battles continue. To cite a more recent example, in 1658 Thomas Hobbes could write:

The love of riches is greater than wisdom. For commonly the latter is not sought except for the sake of the former. And if men have the former, they wish to seem to have the latter, also. For it is not as the Stoics say, that he who is wise is rich; but, rather, it must be said that he who is rich is wise.

And in much the same vein, freshman advisors at Dartmouth recently found themselves in receipt of a comparable document which starts out with nervous questions from students: "For what type of job does a major in History qualify me?" "Should I major in English if I don't want to teach English?" "If I major in Biology, do I have career options other than scientific research?" Official copy from the Office of Career and Employment Services then takes over: Do these questions and dilemmas sound familiar to you? Are you worried that a particular major will prejudice your chances of finding post-graduate employment? . . . Many students believe that the choice of a major determines the course of much of their future lives. Some believe that certain majors qualify them for almost anything. Are these beliefs true of Dartmouth's liberal arts graduates? Read on . . .

There is, then, overwhelming evidence that many today wonder whether a knowledge of the Dark Ages prepares students for Wall Street or, in less metaphorical terms, whether the liberal arts are ever capable of practical application, whether they can ever prepare students for the complexities of life and career as experienced in the final decades of the twentieth century. Here, however, a question arises, how one defines the liberal arts. Over the centuries they have received a multitude of definitions, but whatever the one advanced, evidence shows the extent to which even institutions traditionally committed to the liberal arts are today more than a little nervous about how to justify them.

They shouldn't be, but to understand the point, one must pose a question frequently asked these days: why there should be any education at all. In a sense, the answer is obvious, for if parents have consistently sought to educate their young, that is because each generation has always tried to prepare the next for the rigors of life. That is, in brief, the essence of education. At the same time, though, the very obviousness of the answer tends to obscure its underlying premise, that the nature of the life envisaged will have a significant impact on the nature of the education provided.

Thus, in the early Middle Ages - the Dark Ages, if one prefers - education was exceedingly simple because life was exceedingly tough. Life expectancies hovered near 20 years, and the economy, overwhelmingly agricultural, had become so inefficient that 95 percent of the population had to work full-time on the farm simply to produce the food needed to survive. With 19 out of 20 agriculturally employed, this was surely no time for the liberal arts. Fundamentally, two realities governed the situation. First, children were destined to become farmers since, almost without exception, there was no other choice. Secondly, with the margin of survival so slim, those children had to be taught never to innovate since to innovate was to risk the chance of error, and in such a society, error meant death. So the result was a system of child-rearing in which the younger generation learned to do only what its parents had done and exactly as they had done it.

Change came in the eleventh century. By then, better methods of farming were beginning to improve agricultural production, and with a larger and more dependable food supply, population started to rise. By the twelfth century these developments were leading to rapid urbanization and ever more commerce and industry. But a further result was a crisis in education.

If the peasants of the Dark Ages had found it desirable to stress tradition in rearing their children, the middle class of the twelfth century could adopt no such strategy. Their society was chang- ing so rapidly that new opportunities seemed to spring up daily. As a result, no urban father could ever be sure whether his sons would follow him in his own craft or profession. Yet if they did not, to teach them only the parental skills would be to risk making it impossible for them to get ahead. And in the feisty world of the high Middle Ages, getting ahead was a common ambition.

Because it was, there gradually emerged a new way to bring up the young. Since the person who knew only his father's trade was but poorly equipped for coping with the realities of urban life and urban diversity, it was no longer enough just to pass on parental skills in a kind of familial apprenticeship system. To survive and thrive in the city, children had to have new qualities of independence. Because the greatest opportunities came only to those prepared to strike out in new directions, those just starting their careers needed a different personality, one which included an internalized sense of values, drive, and discipline. Even more importantly, they needed to learn the techniques of problem-solving, of independent thought. For how else could they learn how to learn about the skills needed to advance in still-unknown and possibly not-yet invented positions? How else would they ever learn how to solve the vexing problems with which those positions would inevitably confront them? In short, a society once based on the need for tradition now had to teach its children how best to respond to - and master change.

Strictly speaking, these points are scarcely new, but from the beginning, the evidence suggests that the liberal arts provided an answer because they placed more emphasis on applicable skills than on abstract content. To use terminology from the Renaissance, they held that insofar as ideas should always lead to action, all knowledge had its greatest value only when applied. Consider, in proof, Philo of Alexandria's discussion of why those arts should precede any attempt to study philosophy, a discussion written in the first century of the common era: Grammar teaches us to study literature in the poets and historians, and will thus produce intelligence and wealth of knowledge . . . Music will charm away the unrhythmic, the inharmonious by its harmony . . . Geometry will sow in the soul that loves to learn the seeds of equality and proportion, and by the charm of its logical continuity will raise from those seeds a zeal for justice. v Rhetoric sharpening the mind to the observation of facts, and training and welding thought to expression, will make the man a true master of words and thoughts . . . Dialectic, the sister and twin, as some have said, of Rhetoric, distinguishes the true argument from the false and convicts the plausibilities of sophistry.

Quaint though some of Philo's arguments may now appear, they had both a past and a future. In origin, the idea that one can approach philosophy only after mastering the liberal arts goes back to the Stoics, and its durability is suggested by the fact that this same idea underlies much of the symbolism to be found in Herrad von Landsberg's rose of learning. One can certainly say, therefore, that Philo is here confronting some pretty basic notions about the nature of the liberal arts and their potential usefulness.

Because Philo's commitments were primarily to philosophy, one understands why he should have viewed the liberal arts as little more than the means to an end. Similarly, one can see why, with the possible exception of music, he places his emphasis on skills, not on the mastery of content. On the other hand, it seems a bit more surprising to discover the context within which he stresses those skills. For he sees them as having their greatest importance not as tools with which to study philosophy. Rather, he asserts that their highest value lies in their capacity to help people to succeed in other and more practical fields. Thus one learns geometry not to become another Euclid, but another Solomon, a king ever zealous for justice.

On reflection, though, it becomes clear that Philo's insights are less remarkable than they first appear. If we in the modern world are surprised that he seldom concerns himself with specific content, the problem lies more with us than with him. For what we tend to forget is that even in Greece and Rome the arts were discipline, not specific works, and hence that the materials on which they were based were of secondary importance. Thus, although some have argued that it is impossible to study rhetoric without Dio Cassius or grammar without Statius and Martial, that claim is hardly classical. Rather, it is part of our inheritance from the early Middle Ages, those "Dark Ages" to which this article seems so insistently to return. For if the belief arose that there were seven liberal arts worth knowing, each with its prescribed content, that idea owes its being not to some giant of classical antiquity (though it does have some roots in Isocrates), but to one of the dwarves of the fifth century, Martianus Capella. And about him we know practically nothing other than the possibly linked facts that he was a lawyer and that late in life he wrote one of the dullest books of all time, The Marriage ofMercury and Philology.

Now, to call Martianus a dwarf is greatly to understate the medieval estimate of his worth, for in the Middle Ages The Marriage of Mercury and Philology became a standard text, thus insuring that students would be introduced to the liberal arts largely though its nine books of frightful myth and relentless allegory. Yet introduced not just to those arts, really, since in his quotations and references Martianus also managed to provide what amounted to a standard syllabus of books on which all study was implicitly to be based. Because, moreover, thinkers tended to think of the artists and writers of the past as giants whereas they likened themselves to dwarves, in the eighth century Alcuin, the head of Charlemagne's palace school, could write: "We are like dwarves at the end of all time. There is nothing better for us than to follow these precepts instead of inventing new ones or vainly seeking to increase our own fame by the discovery of newfangled ideas." Similarly, though with greater optimism, at the start of the twelfth-century renaissance Bernard of Chartres would observe: "We are like dwarves seated on the shoulders of giants. If we see more and farther than they, it is not because of our own clear eyes or tall bodies, but because we are upborne and raised on high by their gigantic bigness." Minds like these were unlikely to abandon "the classics" as the basic materials on which to rest their study of the liberal arts.

Nevertheless, even in the Middle Ages a knowledge of the classics remained the means to an end, not the end itself. Ancient authors may have been highly esteemed; some were even greatly enjoyed, though sometimes (as in the case of Ovid) a bit surreptitiously. Yet for all the admiration even of a Virgil, few envisaged entire lives and careers devoted just to him and his poetry. Here, however, two quite different opinions emerged. On the one hand, if a St. Augustine accepted the liberal arts, he did so because he saw their value for sacred studies. To profit from the Bible, after all, you must first be able to read it. Thus was born the "handmaiden-totheology" school of thought, one which held that the liberal arts should always be applied and used - but never enjoyed for their own sake.

On the other hand, with the revivals of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, people began to discover that the liberal arts could also provide useful preparation for those new kinds of careers so typical of an increasingly complex society. They found, in effect, that an education based on the liberal arts could serve as an appropriate culmination for all earlier training. In illustration, however, one example will have to suffice.

Peter of Blois was the twelfth century's version of the perpetual student and poet turned administrator. Born at mid-century, he studied the liberal arts at Blois; law at Bologna; and, finally, theology at Paris. After ordination, however, he found he still lacked a clear vocation. In the end, he was to spend much of his life as the confidential clerk for two archbishops of Canterbury. As he himself attempted to rationalize that development: I do not condemn the life of civil servants, who even if they cannot have leisure for prayer and contemplation, are nevertheless occupied in the public good and often perform works of salvation. All men cannot follow the narrower path - for the way of the Lord is a strait and arduous road, and it is good if those who cannot ascend the mountain can accom- pany Lot to be saved in the little city of Zoar.

Moreover, Peter could at times be remarkable if somewhat penitentially candid about the furies which had shaped his life: I was led by the spirit of ambition and immersed myself entirely in the waves of the world. I put God, the Church and my Order behind me and set myself to gather what riches I could, rather than to take what God had sent . . . Ambition made me drunk, and the flattering promises of our Prince overthrew me ... I shall think over the time I have wasted, . . . and I shall offer up the residue of my years to my studies and to peace. Farewell my colleagues and my friends . . .

Although the parallel may not be exact, in writing like this Peter of Blois manages to sound suspiciously like John D. Rockefeller dispensing dimes. Yet in such evidence - and this whether it comes from Peter of Blois or some other source, one begins to discern the outlines of a second school of thought about the relevance of the liberal arts. This school was not for theologians. Rather, it was for those with less certain futures. Because it was and because, really, it so remains it held that the proper end of the liberal arts is to develop students' reason and judgment, their intellectual capacities, and not just their purely vocational or professional skills. It is, then, a school which favors an education not tied to specific or permanent content, and it is this quality which has allowed it to be remarkably flexible about defining the disciplines which are to be numbered among the "true" liberal arts. If so, though, one must at all times remember if the liberal arts had ever proved incapable of being applied, they would have found it impossible to respond to new realities and hence would have died long ago. That they did not must therefore be seen as evidence of their adaptability, durability, and continuing relevance. Moreover, some of the reasons for this durable adaptability are instructive.

In 1690, when John Locke published his Thoughts Concerning Education, he had occasion to ponder the effectiveness of the traditional disciplines, not all of which he found useful: Rhetoric and logic being the arts that in the ordinary method usually follow immediately after grammar, it may perhaps be wondered that I have said so little of them. The reason is, because of the little advantage young people receive of them. Right reasoning is founded on something else than the predicaments and predicables, and does not consist in talking in mode and figure itself . . . Strikingly, too, Locke was far from alone, for thirty years earlier Thomas Hobbes had taken a remarkably similar position, arguing that: ... it sometimes happens to those that listen to philosophers and Schoolmen that listening becomes a habit, and the words that they hear they accept rashly, even though no sense can be had from them (for such are the kind of words invented by teachers to hide their own ignorance), and they use them, believing that they are saying something when they say nothing.

In short, by the second half of the seventeenth century, some of England's most influential thinkers were prepared to abandon two of the three disciplines comprising the trivium "because," in Locke's phrase, "of the little advantage young people receive by them." Further, Hobbes, like Newton, was prepared to supplement them with newer and more practical disciplines that were based only in part on the skills of the quadrivium: The sciences ... are good. For they are pleasing. For nature hath made man an admirer of all new things, that is, avid to know the causes of everything . . . From these things the enormous advantages of human life have far surpassed the condition of other animals. For there is no one that doth not know how much these arts are used in measuring bodies, calculating times, computing celestial motions, describing the face of the earth, navigating, erecting buildings, making machines, and in other necessary things ... So it is that science is the food for so many minds, and is related to the mind as food is to the body; and as food is to the famished, so are curious phenomena to the mind. They differ in this, however, that the body can become satiated with food while the mind cannot be filled up by knowledge.

Here, at last, one begins to see why a knowledge of the Dark Ages should prepare students for Wall Street. For thanks to the revolutions of the seventeenth century - revolutions which had at different times been either Puritan; glorious, or scientific - the nature and number of the liberal arts had been strike ingly transformed, though this is not to say that the transformation had in any way put an end to the fights about and between them. Contrary to Locke's hopes, for example, the trivium didn't just roll over and die. Instead, as late as 1835 Thomas Babington Macaulay can be found complaining: Give a boy Robinson Crusoe. That is worth all the grammars of rhetoric and logic in the world . . . Who ever reasoned better for having been taught the difference between a syllogism and an enthymeme? Who ever composed with greater spirit and elegance because he could define an oxymoron or an aposiopesis? I am not joking but writing quite seriously when I say that I would much rather order a hundred copies of Jack the Giant-Killer for our schools than a hundred copies of any grammar of rhetoric or logic that ever was written.

Still, educational reform being what it is, even Macaulay's observations probably did more to get Robinson Crusoe and Jack the Giant-Killer into the curriculum than rhetoric and logic taken from it. Thus it is that they still have their place, though often disguised under different rubies such as "Communications" or "Language Arts."

Yet, whatever the cas.e, this mention of children's stories suggests that the argument is starting to come full circle. If so, it is time to repeat the question, whether a knowledge of the Dark Ages prepares students for Wall Street. Now, however, it seems possible not just to answer it, but to say something further about the liberal arts today. For yes, a knowledge of the Dark Ages will prepare students for Wall Street, and in ways that merit discussion.

It goes without saying, perhaps, that at the start of careers, college graduates who have majored in medieval history will know more about Martianus Capella than about investment banking. After all, few historians spend much time explaining the difference between bonds and debentures; few even know themselves that stocks have price/earnings ratios and something called betas. What Wall Street novices quickly discover, though, is that what they once learned in class has indeed prepared them for learning, and learning quickly, about the technicalities of career.

That the liberal arts continue to retain their practical applicability may seem surprising in today's world, but it really shouldn't be. Precisely because those arts have always concerned themselves more with skills than with coqtent, they retain a ready transferability and hence can always respond to changing circumstances. For what is learned with one set of facts can easily be applied to others. In history, for example, because one is constantly concerned not just with change, but with explanations of change, students are forced to search out causes and to make discriminating judgments between and among them. Thus, to explain the Dark Ages, they must first consider the fall of Rome, and to understand that, they must master not just a body of factual material but, even more important, forms of sophisticated argumentation about meaning which have developed only over the course of centuries.

In effect, even though students think they are studying causes, they are really learning how to analyze consequences, how to predict (as they will later have to do in the "real world") the likely results of decisions made. As a result, to major in history is not just to gain knowledge of the past, rather, it is to use the past as a kind of laboratory, the equipment and models of which allow students to acquire skills without all of the risks inherent in having to gain them on the job. It is, after all, infinitely preferable for someone to learn from being wrong about the fall of Rome than about the performance of the stock market today. Yet, because that is so - and because what one learns about the Dark Ages turns out to have relevance on Wall Street - it follows that, except for purely mechanical details, investment banking (or, really, almost any other form of practical endeavor) is little more than a type of applied history or, more generally, of the applied liberal arts.

In short, to study the medieval past is to acquire practical skills, but it is also to acquire much more: a love of the Middle Ages. This is; of course, a dimension of the subject unmentioned thus far, but here, at the end, it deserves some stress. For if the purpose of the liberal arts in a purely functional sense is the development of skills, still it is true that even the most utilitarian among us must at some point acknowledge this other dimension which the liberal arts should have in our lives. Moreover, because this dimension so far transcends the "merely useful" or "purely practical," it seems most unlikely that history, the humanities, or any of the other liberal arts will ever lose their appeal or relevance, rejected by a world in which all must be applied, practical, and measurable. On the contrary, this very duality insures their survival. So if, at times, the fearful claim that the sounds coming out of contemporary Washington prove that a knowledge of Wall Street is preparing us for the new Dark Ages, with Gregory the Great we should all respond: "let not your mind be in any waydisturbed. For these are but signs of the endof the world."

Charles T. Wood, Daniel Webster Professorof History at Dartmouth, worked on WallStreet in 1957 as a trader for First BostonCorporation. His earnings helped pay for hisgraduate work in medieval studies at Harvard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Apple on Every Desk

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Train Robbery

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wentworth Bowl

June 1985 By Barbara J. MacAdam, Curator, Hood Museum of Art -

Cover Story

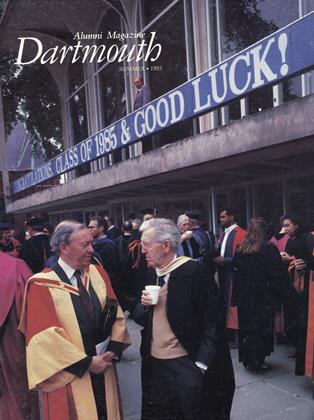

Cover StoryValedictory Address

June 1985 -

Feature

FeatureReunions 1985

June 1985 By Robert Frost -

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June 1985

Charles T. Wood

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JUNE 1971 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1978 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY • 1988 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorThe Games Were Glorious

MARCH 2000 -

Feature

FeaturemAgnA CARTA: Seventh Crisis of John Plantagenet

November 1973 By CHARLES T. WOOD -

Perspective

PerspectiveWar and Remembrance

Jan/Feb 2002 By CHARLES T. WOOD

Features

-

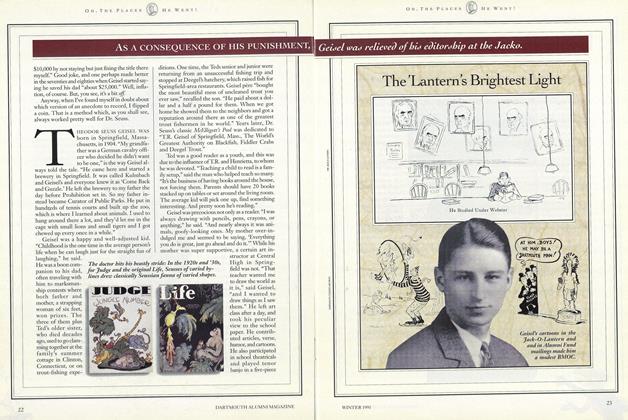

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991 -

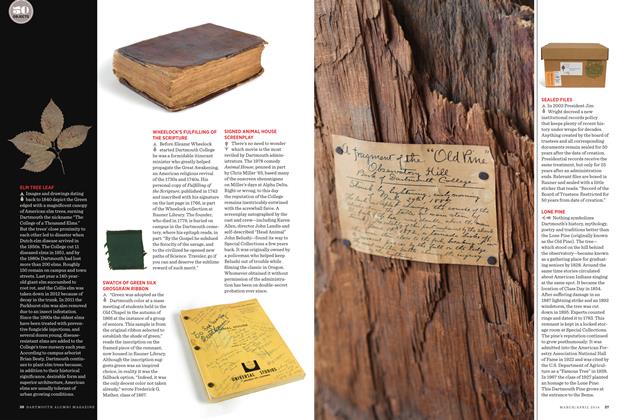

Cover Story

Cover StorySWATCH OF GREEN SILK GROSGRAIN RIBBON

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureArtists in Residence

OCTOBER, 1908 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

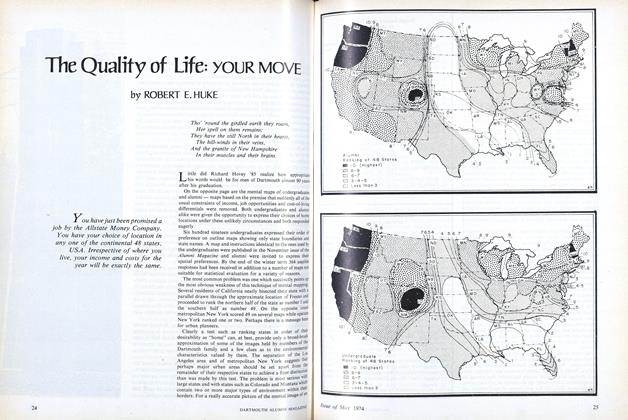

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

May 1974 By ROBERT E. HUKE -

Feature

FeatureReaching Out from Hanover

MARCH 1969 By Ron Talley '69