(or how Orton Hicks '21 got to Dartmouth)

One of Dartmouth's luckiest moments was one of Yale's unluckiest. The moment isn't recorded in any official history of the College, and you can be sure it won't be in Yale's. Yet countless alumni have retold it for decades, with and without the facts, and one recent graduate went so far as to include it in her valedictory address. The moment belongs to Orton Havergal Hicks, Dartmouth '21, Tuck '22.

"I guess it was my greatest example of doing the right thing for the wrong reason,"Hicks says as he slides back in his armchair with a characteristic chuckle. "I had two roommates at Shattuck prep school in Minnesota. One was Riney Rothschild, who was sold on Dartmouth. The other was William Benton, who came from generations of Yalies. My mother was heartbroken when I refused to go to Harvard, but she was willing to settle for Yale. So Benton and I sent a letter and a check for $10 to secure a room in New Haven.

"A week before we were to leave for school, I heard from Benton that he'd flunked his college entrance exams and had decided to go to Carleton for a year. I didn't want to go all the way to New Haven on the train alone, so I went to St. Paul and took the train with Riney. After we'd gotten out of Grand Central, Riney put on the hard sell. By the time we got to New Haven, he'd convinced me I'd be out of my mind to go to Yale. I stayed on the train, went to the registrar the next day in Hanover and signed up for classes. It wasn't that hard to do back then."

Hicks arrived in Hanover with a deep sense of obligation; his mother had taken a job as a millinery worker to pay for his education. He also had a clear sense of purpose. Freshman fall, Hicks ran the only 4.0 average in his class. As classmate R. De Witt Mallary attests, there wasn't anyone in the class he didn't know. But after his Phi Gam brothers persuaded him to run for the class presidency, a position he won and held for two years, Hicks claims he made all the wrong moves: "Once I got all A's, I decided to major in extra-curriculars."

The College and the Class of '21 aren't complaining. He went on to serve on Palaeopitus, gain entrance into the Proof and Copy journalism society and its elite counterpart, Phi Delta Epsilon, start Green Key, lead the Big Green ROTC contingent and, though lean at 150 pounds, even play center for two years for C.W. Spears's football squad - a move he writes off as an attempt to balance out the "black mark" of his notoriety as a superior student.

The same spark that made Hicks a campus leader put him at the forefront of the film-distribution field. He started as a salesman at Eastman Kodak in 1922 and moved eventually into, his own business, the Seven Seas Film Corporation.

During World War II, the armed forces needed 16mm films to circulate overseas and run on portable projectors. Since no one had converted, packaged, and promoted small reels longer than he, Hicks was a natural choice. The War Production Board offered him a dollara-year job in Washington, a job he took with gusto. Together with his closest friend, Jack Hubbell '21, Hicks gave the military first-rate movie entertainment by putting unreleased American hits on folding screens overseas.

Arthur Loew, founder of Loew's International (later MGM), followed him closely. Once Hicks's tour of duty was up, Loew hired him to widen the international market for MGM. He stayed for 13 years, until Dartmouth called on him in 1958.

President John Sloan Dickey '29 had had his eye on Hicks ever since he had supplied a first-rate picture - written and produced by Maury Rapf '35 - for Admissions in 1950. He also knew that Hicks had persuaded his Great Neck neighbor Hoyt Miller, whose father, Dartmouth 1870, had guided The NewYork Times into international prominence, to leave the College enough Times stock to start the Great Issues course. Dickey needed a right-hand man with connections and drive. So he invited the Hickses to spend Winter Carnival on Webster Avenue.

"Just before we were going to leave the Dickeys on Sunday," Hicks recalls, "John turned to me and said, 'Ort, we have a chance to hire a vice president for public and alumni relations, fundraising, and long-range planning. May we consider you?' " Hicks declined, pointing to the fact that he'd just signed a new five-year contract with MGM. "The real reason," he says, "was I knew that public speaking was involved, and I'd never done much of it and was truly scared to death of it. I loved Dartmouth and wanted only the best for the College a man who could open any door -

and I was far from the best. I thought of Doc O'Connor '07 or John L. Sullivan from my class." But the President persisted. He not only learned from Arthur Loew that the MGM founder planned to retire before the summer, he persuaded him to let Hicks out of his contract. "Two months later, in April of 1958, John called me again," Hicks says slowly, with a smile. "I told him I still thought I wasn't the right guy for the job, but since he'd already looked for more than a year and found no one, I'd talk to him. So Lois and I went to Hanover and found our house on Rope Ferry."

Arthur Loew didn't want to lose his favorite director, but 13 years had shown him that, while Hicks had left Hanover 37 years before, his heart was still there. He had served as vice president of the Long Island Alumni Club, two years as secretary of the Dartmouth Club of New York, six years on the Alumni Council (including a year as president), and a year on the Board of Overseers of the Tuck School. Loew had only one reservation about Hicks' new job. As Hicks explains, "When I asked Arthur what he thought [about President Dickey's offer], he said, 'Ort, I think it's great for you, but I'm not so sure it's such a good deal for the College. Ever since you've been with me, I've noticed that you spend about 90 percent of your time on Dartmouth. I'd like to know how much the College is paying you for that extra 10 percent."

Hicks was quick to put his film connections to work for Dartmouth. He approached the wife of his late friend and MGM chairman, Nicholas Schenck, to get funding from the Schenck family foundation for a film program at Dartmouth. Although her husband wasn't an alumnus, Mrs. Schenck warmed to the prospect; she donated $15,000 for a three-year launch of film studies. With check in hand, Hicks hired a wellknown film veteran, Arthur Mayer, then about 78, to teach a film history course. Maury Rapf, whose successful career as a producer was launched by Hicks, was lured back to Hanover in 1965 to teach film. Rapf remembers that Hicks' onthe-spot'hiring caused some controversy. "Film wasn't a widely-accepted course of study on campuses at the time," Rapf recounts. "There were many diehards on the faculty who didn't think film study wAs legitimate for a liberal arts curriculum. Ort was ahead of his time."

Mayer soon became a campus celebrity, (as a memorable New Yorker profile revealed and more than 200 students enrolled in his "History of Film" class the year he retired. Shortly after Hicks started the Film Studies program, he tapped his contacts to bring the Conference on Film Study and Higher Education to Dartmouth. The assembly of scholars won the College prestige in the film world and a place in American film history; for out of that conference the American Film Institute was born.

To hear Ort Hicks tell it, fundraising was the opportunity of a lifetime. People were, after all, the joy of his life, and President Dickey made them an integral part of his job. As his colleague and successor to the vice-presidency, George Colton '35, puts it, "Ort got the opportunity to come back to live and work in the College he loved so much. It was natural for him. All he had to do was go see all those people he loved, and strengthen in their hearts the pride in Dartmouth he felt so deeply in his own."

To make the most of his new challenge, Hicks mapped out a gruelling schedule that sometimes made Hanover seem a waystop between trips. By the time he officially resigned from the College, he'd spoken at every alumni club in the country. When he was in Hanover, as often over the weekend as during office hours, the phone rang and the Hicks home at 6 Rope Ferry was virtually an open house to alumni and friends. Hicks' gracious wife Lois, often the last to learn of important dinner guests, answered Dartmouth's call with a warmth that has won her a place in the hearts of hundreds of alumni. "I couldn't have done it all without George [Colton] in the office and Lois at home," says Hicks. Hospitality and friendship were extensions of Hicks' personal approach to his job. For one thing, alumni were friends he longed to welcome back to the College. For another, the gift of giving was a gesture of pride and joy.

Hicks has helped better the College as much as he's helped brighten the lives of fellow alumni. Some of his friends have bestowed the wherewithal to take Dartmouth major steps ahead in computing, athletics, and continuing education: Thomas Murdough '26 (Murdough Center for Continuing Education, Tuck School), Martin Remsen '14 (Remsen building, Dartmouth Medical School) Nathaniel Leverone '06 (Lever- one Field House). And these are just a few in a long list that includes James D. Vail '5O (Vail building, Dartmouth Medical School), John B. Cook '29, Gregory M. Cook '69, TH '70, Harold C. Ripley '29, Robert J. Rodday '40, TU '41, E. Winston Rodormer '27, the Reliable Electric Company (Cook Auditorium, Tuck School) and Theodora and Stanley H. Feldberg '46 (Feldberg Library, Tuck School).

It would have been easy for Thomas Murdough '26 to grow disappointed with the College. Dartmouth turned down all three of his sons, but with a friend named Ort Hicks always willing to take time out to help ease the sting, Murdough never turned his back on Dartmouth. A past president of American Hospital Supply, he planned to leave Dartmouth part of his estate but hadn't found the right gift. One weekend at the Murdough's summer home on Squam Lake, Hicks produced a justfinished architect's drawing of the TuckThayer complex, leaving it with them for a week. When Murdough returned, he offered Dartmouth a fortune in stocks that started the construction of the magnificent Murdough Center.

More than 50 years ago, Martin Remsen '14 helped his next-door neighbor, a fellow named Thomas Watson, rebuild a failing typewriter company into a corporate giant. The stock that Remsen amassed over the years in that company IBM allowed him to retire early to Hanover. A longtime friend, Remsen had shared with Ort his plan to leave the College a portion of his holdings. When Dartmouth decided to expand the med school, Hicks turned to Remsen.

"The day before the Remsens were to leave for their winter home in 1968," Hicks remembers, "I brought Martin together for luncheon with the dean of the medical school. After driving the dean back to his office, I stopped the car in front of the school, which was then a little one-story building, and said, 'Mart, we need to add five stories to that onestory building, and we want to name it Remsen Hall.' " Honored but unsure he could do it, Remsen took some time to think it over. Two months later, he called to say he was flying north for a football banquet and wanted to spend the night on Rope Ferry. "The morning after the "banquet," Hicks remembers, "he asked me to drive him to the bank. We sat down at a table inside the safe deposit vault, and after he'd counted a pile of stock receipts, he smiled and handed them to me." It was substantially more than the project called for.

Nathaniel Leverone '06, who founded the famous Canteen company, lost faith in Dartmouth during the '50s. Swayed by the suspicions of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, Leverone suspected that President Dickey had been tinged by antiAmerican sentiment when he was in the State Department and had made the College a hotbed of communism. He generously supported Northwestern, whose president was a neighbor and close friend, but he turned his back on the College. It hurt Hicks to see a fellow Phi Gam so down on Dartmouth. Sensing that it hurt Leverone, too, he resolved not to let him maintain a sourness he might someday regret. Remembering that Nat shared his own passion for Harvard games, Hicks got Coach Bob Blackman to make room for the Leverones on the team bus to and from the Cambridge game one year.

The trip rekindled Leverone's mitment to Dartmouth. A few years after he sold Canteen to ITT, Leverone donated money for the fieldhouse that bears his name. And Dartmouth came to mean so much to Martha Leverone that she left a large contribution to the Thompson Arena project in her will.

For Hicks, the game of solicitation is but the necessary means to a far greater purpose. "I don't think there's anything more important in this world than knowledge tempered with conscience," he muses. "That is what Dartmouth is doing: giving students knowledge and tempering it with conscience. When I look at the students in Dartmouth today, I think back to the prestige in the academic world that Dartmouth has attained in these 68 years since I entered the College; and I'm ever so grateful for the chance to play a small part in that. I only wish I'd had more time to help raise money. That was the only service I could really do for the College." George Colton concurs: "Ort loves Dartmouth with a passion. That's why he does what he does so well. While he loves the game of raising money, he genuinely loves people."

When he signed on with the College, Hicks sensed fundraising was a career that wouldn't end with formal retire- ment. The 19 years since he left the vice presidency have proved that he knew the job as well as he knew himself. When he retired, a long talk with Lois convinced each of them that the future of Mary Hitchcock Hospital would become their next challenge. While he refused a salary, he accepted a desk, a phone, and a secretary. His phone still buzzes with calls to friends of Dartmouth and Mary Hitchcock; weekdays find him working at the dining room table he uses as a desk, or en route with President McLaughlin to Dartmouth dinners across the country; and weekends often find him pouring through files and directories in Blunt.

When Hicks talks about his career at the College, the sparkle in his eyes says it all: his service has sustained him. The fellowship of fundraising is so integral to his well-being that colleagues find it almost inconceivable that he will ever stop. "Not unless his physical condition forces him to," quips Colton. "Raising money for the College has given him a host of friends ... all of whom have shared with him his love for Dartmouth. That's a big part - perhaps the biggest part —of what makes him tick."

Hicks' colleagues in the Blunt Alumni Center concur. Allan Dingwall '42, associate director of the alumni fund, marvels at his persistence. Mike McGean '49, long-time secretary of the alumni, admires the Hicks exuberance that never fails to "make people loosen up and feel better." As much as they revere him, though, few take Hicks as a model; he's simply too tough an act to follow. "When they made Ort," says former vice-president Ad Winship '42, "they broke the mold. I don't know anyone like him."

Today, Hicks says he enjoys "being lazy." When he's not at home overlooking Occom Pond, he's either touring the country or strolling the Hanover streets. His children are among his closest companions. Ort Jr. '49, Tuck '50, now director of development at the hospital, and daughters Carol and Wendy, both married to Dartmouth men, all live nearby. And he's never very far from a tennis court. "No mediocre player ever got more acclaim in squash and tennis," he says of himself. (He and Ort Jr. captured the eastern father-son doubles crown arid placed fifth nationally in 1951. The same year, he later teamed with Arthur Loew to rank third in the East.) Until a Series of injuries finally necessitated a hip replacement, last fall, he took to the squash or tennis court five times a week. His hip operation relegated Hicks to a recliner for a few months, but he bounced right back. His friends won't be surprised if he breaks his promise to Lois and hits the courts this summer.

For all the grand memories that must come back to him in quiet moments, none touch his heart like the day the late Arthur Virgin '00 endowed a music professorship at Dartmouth. Aware that music had drawn the Virgins to Canada, and that the Hopkins Center needed a music enthusiast on its board, Hicks put Virgin on the Hopkins Center Committee and into close contact with the musicians who had thrilled him for decades. When the College needed an endowment to keep the music department flourishing, Virgin made it possible. "When we were leaving," Hicks recalls, "Arthur put his hand on my shoulder and said, 'Orton, the most wonderful years of my life have been the last ten, since you brought me back into the Dartmouth fellowship.' That was one of the most beautiful moments of my life." And to think it all started on a train headed for New Haven"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Humanist Ponders the Future of Liberal Education

June 1985 By Charles T. Wood -

Feature

FeatureAn Apple on Every Desk

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

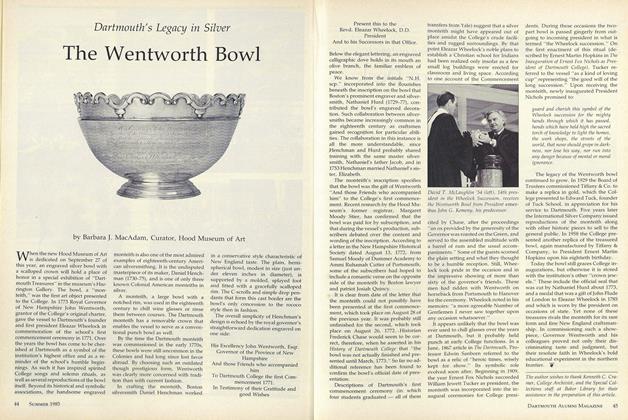

FeatureThe Wentworth Bowl

June 1985 By Barbara J. MacAdam, Curator, Hood Museum of Art -

Cover Story

Cover StoryValedictory Address

June 1985 -

Feature

FeatureReunions 1985

June 1985 By Robert Frost -

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June 1985

Fred Pfaff '85

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Cunningham Classic

June 1960 -

Feature

FeatureJULIO ARIZA

Nov - Dec -

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

MARCH 1989 By David Birney '61 -

Feature

FeatureD C U

May 1956 By GEORGE H. KALBFLEISCH -

FEATURES

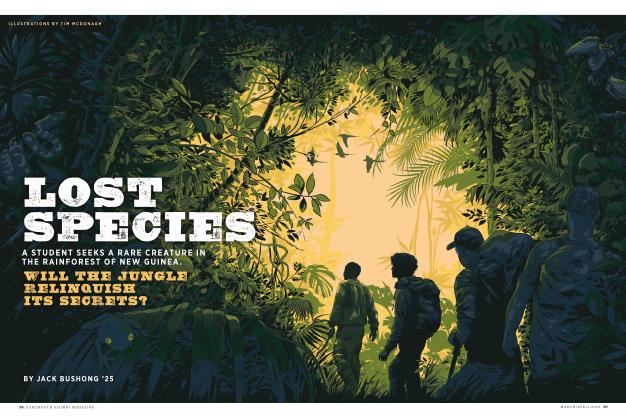

FEATURESLost Species

APRIL 2025 By JACK BUSHONG ’25 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO NAIL A PERFECT FIELD GOAL

Jan/Feb 2009 By NICK LOWERY '78