For a working-class kid atDartmouth part of theeducation was accepting thatit belonged to her

THE ADVENTURE of having been unmoneyed at an unashamedly moneyed institution makes accidental comrades of those who have traveled the same path, whether they graduated in 1979 or 1929. Mapping the passage from working-class kid to Ivy League student is perilous, however; one is always in danger of sounding like a character out of Monty Python's brilliant comic sketch known as "The Four York shiremen."

If you were out of town or not yet born in the seventies, you might not remember the sketch, but otherwise I'll assume that you, too, know it by heart. It's the one where John Cleese and company imitate endearingly single-minded geezers who grew up poor but who'd gone on to make money. These good souls, having accumulated their fortunes, end up spending their golden years competing over who endured the worst childhood. Each one wants his youth to be supremely pathetic. "You lived in a slum?" challenges one. "Well, you were lucky. Me and my family lived in a paper bag in the middle of the road." Another counters, "You had a paper bag? You were lucky. We would have killed for a paper bag. We lived inside the pieces of broken bottle tossed into the gutter under a bridge...."

You get the idea.

I don't want to sound like those guys but I do want to talk about what it was like to be a need-based scholarship student at Dartmouth. I don't expect plaintive violin music to accompany me here. I was never hungry. I was certainly never thirsty—it's tough to be thirsty at Dartmouth. I was often cold, but that had at least as much to do with vanity and a sense of style (which prevented me from placing any garment stuffed with down near my person) as it did with anything remotely approaching poverty. Real poverty—the kind much of the world lives in, the kind much of rural New England and urban New York lives in, for example—l was fortunate enough to escape. So where's the story?

To get to it: I come from a working-class family. My father and a couple of his brothers made bedspreads and curtains in a loft on New York's 25th Street, sewing the fine fabrics themselves on rickety old machines. Nobody in my family had graduated from high school except for my older brother, and he was busy living what we will for the sake of propriety, now that he is an attorney with an M.B.A., refer to as an "intense" life during the late sixties and early seventies while I toiled at more pedestrian school-related tasks such as taking exams and considering college.

The very idea of college was a particularly big deal because no woman in my family had ever thought about it. True, the younger generation worked outside the house, employed as telephone operators, as receptionists, as hairdressers, from the day they left school until the day they got married. But that was usually a pretty short span of time. In contrast, I nursed ambitions no doubt derived from my Canadian mother's side of the family, where education was highly prized but regarded as all but unattainable. I wanted to keep studying.

In my senior year I applied—more or less in secret to three schools: Queens College (near home), McGill University (in deference to my mother's Quebecois heritage), and Dartmouth, because my high school history teacher had visited the place and knew that they'd recently admitted female students. His intentions were in the right place—but neither he nor I knew anything about what we were getting me into when I filled out that application in the early winter of 1974, answering the essay questions in peacock bine ink from a plastic cartridge pen, clueless that I should have been using a typewriter.

Not that we owned a typewriter. That was my reward for being accepted into Dartmouth: my father bought me a huge, preposterous machine two weeks before college started, a typewriter the size of a Harley Davidson. I loved it. It was about as convenient as lugging around a side of beef, but somehow it made me feel as if I were a bona fide college student.

Dad drove me up to Hanover in a 1967 silver gray Buick Skylark. Recently widowed, my 53 -year-old father had no idea what this experience would be like for his only daughter and offered few comments on the drive up 1-91. He asked me, simply, "What's the worst that can happen?"

What did happen? Nothing dreadful, only I was excruciatingly conscious of the fact that I spoke funny, dressed funny, acted funny, and didn't fit in. Let's put it this way: I most certainly didn't have what F. Scott Fitzgerald would have described as a voice full of money. When I put on a Laura Ashley peasant dress, I didn't look like a sweet little English lady, I looked like the girl on the front of a can of Contadina tomato sauce. I knew I was out of place, and I didn't believe I'd make it through my firstyear. On one level you could say, quite correctly, "Big deal. You were in Hanover to get an education. You did make it through, and Dartmouth provided one monumentally beyond what you could have imagined or afforded without its aid. You should shut up and count your blessings." Or, in the words ( ofMonty Python, "You were lucky."

On a number of other levels, however—and maybe you have to remember what it was like to be 18 and out of your league to really understand this—it was genuinely terrifying. Nice people asked me where my brother went to college and where my father worked. When I told them, they were slightly baffled by my answers and looked at each other dubiously to see if I were pulling their collective leg. Nice people asked me where I skied—I had never skied. Nice people asked me if I'd tried those great new boots from L.L. Bean—I had never heard of L.L. Bean. Even nicer people asked me if I wanted to go to The Bull's Eye, or Jesse's, or Peter Christian's but I always worried that the money I made at my work-study jobs was not going to be enough to get me through to the end of the term, and I didn't want to be a parasite. I sold my books back when I really wanted to keep them. I worried about being broke, about asking my father for cash, about the enormous number of loans I was taking out, about small debts to friends. In the middle of some anxious nights, I wondered how I became a foster-child of this affluent institution.

My father and brother would drive up from Brooklyn once a term to visit me. Other folks' families came up and stayed for parents' weekend or homecoming. My family would drive back late the same night because it never would have occurred to any of us that they spend money on a room and stay longer. My brother would study the leggy, graceful girls, sleek as thoroughbreds, and comment on the disparity between them and my friends back home. I'd laugh along, chiding him, but I knew what he meant because the burnished, blue-eyed boys walking around campus looked pretty different from what I'd experienced back home, too.

What remained entirely out of my reach was the polished look that comes from being a kid from a family with a solid financial and social foundation. We're not just talking good genes here. We're talking about something more complex, often referred to as breeding, a combination of inherited gifts and nurtured talents. As hard as it is to define, it is nevertheless essential to understand: people—not necessarily the irrefutably rich, but the socially and culturally privileged—have a distinct way of handling the world, as if they are simply overseeing what belongs to them. I didn't have this and I couldn't fake it.

I also couldn't name it, couldn't get my mind wrapped around the concept until, in an independent study on the modern novel, I fell into a passage from John O'Hara's Butterfield 8:"All her life Emily had been looking at nice things, nice houses, cars, pictures, grounds, clothes, people. Things that were easy to look at, and people that were easy to look at; with healthy complexions and good teeth, people who'd had pasteurized milk to drink and proper food all their lives from the time they were infants; people who lived in houses that were kept clean, and painted when paint was needed, who took care of their cars and their furniture and their bodies, and by doing so their minds were taken care of; and they got the look that Emily and girls—women—like her had."

I didn't have "the look," and so literally couldn't look at things from the same perspective. I had good grades and the stuff it took to get good grades. I had a bravado that often was mistaken for strength. I had a big mouth that was sometimes interpreted as self-confidence. And while I substituted swagger for poise and unashamedly used my sense of humor as a way to camouflage my almost perpetual discomfort, I couldn't fool myself or anyone else into thinking that Dartmouth was the kind of place that would have always let me in the front door. True, Dartmouth took "charity" students from the very beginning, and more than a few nineteenth-century students worked during the winter to earn enough money for spring-term studies. But I think I was confronting something slightly different—not worse, but different—from what those earlier students had faced.

Thirty years before my admission, half French-Canadian girls could never have expected to do anything in Hanover but wash floors. Half-Italian girls might have worked in kitchens or bars. Girls like me would have lived in boarding houses, not dorms; they would have averted their eyes from college boys for fear of being thought too easy or too bold.

I have become increasingly aware of the way in which my place at the College helped me recognize contradictions in my own attitudes towards traditional roles within my family, as well as to face—and even challenge—my own ambivalence about the larger implications of success. In retrospect, I think that I both exploited and evaded the confines of the role of working-class-kid on campus. True, I saw social and economic spikes everywhere and rushed to impale myself on them. But also, in time, I came to accept that the education and experience were mine—not just things that had been lent to me, like somebody's earrings or their car, to be returned undamaged and unsoiled at a later date. Finally, I believe that a good education is always subversive, even when it ostensibly endorses conventional moral and cultural doctrines, and so I know that only a very good education could have prepared me to be a troublemaker and, in the end, I am indeed grateful. You could even say that I am lucky.

The very idea ofcollege was aparticularly bigdeal because nowoman in myfamily had everthought about it.

I sold my books backwhen I really wantedto keep them. Iwondered how Ibecame a foster-childof this affluentinstitution.

What remainedentirely out of myreach was the polishedlook that comes frombeing a kid from asolid financial andsocial foundation.

REGINA BARRECA is an author and English professor at theUniversity of Connecticut. You can visit her "Untamed andUnabashed" web site at .

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

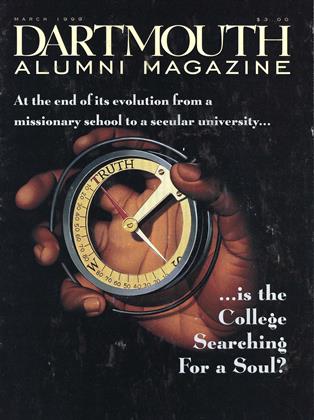

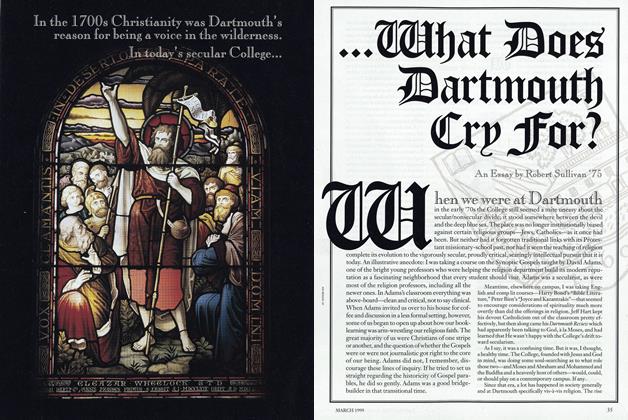

Cover StoryWhat Does Dartmouth Cry For?

March 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureFirst person

March 1999 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

March 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleExercising the Mind

March 1999 By Rich Barlow '81 -

Sports

SportsSilver Honors for Ivy Women

March 1999 By Sarah Hood '98 -

Article

ArticleStanding Together

March 1999 By James Wright

Regina Barreca '79

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorWhither the Greeks?

MAY 1999 -

Feature

FeatureThey Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted

June 1992 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

FEBRUARY 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Eleven Commencing

June 1995 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMater Dearest

MARCH 1997 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Feature

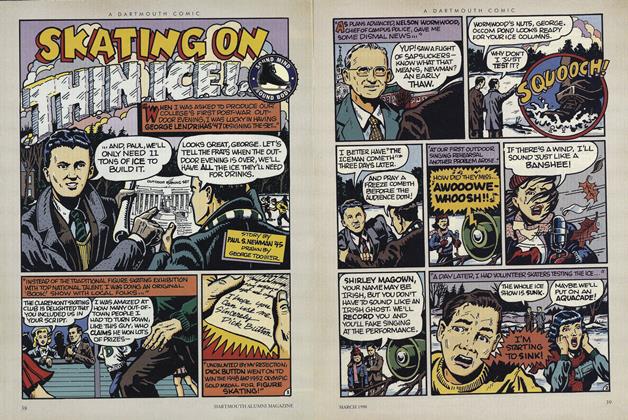

FeatureSKATING ON THIN ICE!

March 1998 -

Feature

FeatureTo Screenwriting Born

November 1982 By Budd Schulberg '36 -

Feature

FeatureA CHANCE FOR THE PENTAGON TO HELP SOLVE SOME DOMESTIC AS WELL AS MILITARY PROBLEMS

MAY 1970 By GERALD G. GARBACZ '58 -

Feature

FeatureNew York Art Show Planned

JANUARY 1970 By H. ALLAN DINGWALL '42 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOur Altar

APRIL 1997 By MARIANNE CHAMBERLAIN '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRousseau Cops an Exam

MARCH 1995 By Philippa M. Guthrie '82