Some of the hottest and, arguably, the finest—novels were written centuries ago.

The major networks would have loved to cut a deal with the ancient Greek novelist Heliodorus. His novel, An Ethiopian Story, is just the type of property that merits sixfigure advances. The tale, published in the latter part of the fourth century A.D., begins with a young woman defending her chastity and features adventure, lust, intrigue, lust, chase scenes, and more lust all the ingredients that send Nielsen families drooling to their diaries. Potential mini-series not withstanding, though, does Heliodorus's novel representative of an ancient genre typified by swooning virgins, iron-loined heroes, and palpable passion really have any place in the literary canon?

Dartmouth Classics Professor James Tatum thinks so. In agreement are at least 130 scholars from 17 countries who spent a week in Hanover last summer at a conference on the ancient novel. Conferees discussed such scintillating subjects as "Erotic Narrative: Virginity and Going the Whole Hog" and "The Erotic Bath in Byzantine Vernacular Romance," as well as more sober conference fare characterization, theme, and translation.

Tatum, who organized the conference, acknowledges that the phrase "ancient novel" sounds like a contradiction in terms. But fictional prose narrative was one of "the major innovations of Greek literature," he says. Despite what most histories of the novel suggest, by about 200 A.D., "prose fiction was a well-developed, sophisticated form."

if you didn't know this, you are not alone. The evidence or in this case the lack of it suggests that the ancient novels didn't make as much of an impact as first editions. In all of the ancient writings available to classicists, there are only a handful of references to works of fiction. Unlike, say, the plays of Euripides, novels had no place in the ancient curriculum.

Prose fiction was, in Tatum's words, written for "ultra-sophisticated readers, not for the kiddies." He believes that the ancient novelists subverted the literary norms of their time. "In antiquity," he explains, "prose was the medium for official communication, for persuasion, for telling what had actually happened. You looked to the poets for myths, things that weren't true but might be true. A novel blurred two things that were supposed to be kept apart: the poet's myths and the historian's truth."

Adding to the novels' obscurity is their rarity; only about about 1,000 pages of text survive. What remains includes about a dozen novels and many more fragments of stories with scenes that range from seemly to steamy. In the introduction to his book, Collected Ancient Novels, classicist B.P. Reardon of the University of California (Irvine) describes the typical plot: "Hero and heroine are always young, wellborn, and handsome; their marriage is disrupted or temporarily prevented by separation, travel in distant parts, and a series of misfortunes, usually spectacular. Virginity or chastity, at least in the female, is of crucial importance; and fidelity to one's partner, together often with trust in the gods, will ultimately guarantee a happy ending." Here is an example of young, well-born and handsome characters who figure in the novel Daphnis and Chloe by Longus. Because this is a respectable magazine, we've chosen a relatively mild passage:

He asked Chloe to give him all that he desired and to lie naked beside his naked body on the ground for longer than they used to before. This, he said, was the sole cure and antidote for love. She asked what more there was than kissing and embracing and actually lying down naked together and what he proposed to do when they were lying down naked together.

"Obviously, the ancients weren't sitting around in white robes talking philosophy all day," notes William S. Moran, a classicist and a librarian at Baker. "This was soap opera, this was adventure, this was cliff-hanger, this was sex and gore." Moran adds: "This was wonderful."

Yet he and Tatum stress that, as far as scholars can tell, the ancient novels were rarely that simple. They maintain that the best of the books those written by Achilles Tatius, Heliodorus, Petronius, and Apuleius are every bit as "devious" as Vladimir Nabokov and as complex as James Joyce. "Put Petronius's Satyricon side by side with Joyce's Ulyssessays Tatum, "and you'll find astonishing similarities in structure, in narrative non-technique, in the way the pace and tone and interpretability of events is constantly changing." Tatum says other mainstays of modern literature were inspired by ancient works. For instance, Fitzgerald's Jay Gatsby is an update of Trimalchio in Petronius's Satyricon.

Modern classicists are hardly the first to appreciate ancient novelists. During the Renaissance, the literati recognized the authors' pioneering work. Heliodorus, for instance, was on the must-read list of the educated elite. Later literary masters including Cervantes, Calderon, Fielding, Racine, and Shakespeare all revered and imitated the ancient authors.

The rave reviews didn't last. By the nineteenth century, German philologists set the standard for what a "classic" should be. With few exceptions they were unified in their loathing of the Greek novels. The Latin novelists Petronius and Apuleius fared even worse, being considered the degenerate offspring of the Greeks. According to Tatum, the ancient novels' plummet in status reveals more about arbitrary notions of the "classics" than the quality of the literature itself. "Texts like these were seen as debased forms, signs of decadence, signals of the collapse of the ancient world," says the professor. "The nineteenth century had its vision of what the classical world ought to be, and texts that didn't fit that image were just pushed aside."

Today, however, the ancient novel is recovering a readership particularly an academic one. As contemporary scholars have taken a new interest in ancient novels, there has been a corresponding rise in the number of translations. Last year marked the publication of the first complete English translation of all five extant Greek novels. In the future, students can expect to see names like Longus, Achilles Tatius, and Heliodorus appearing in more college curricula. At Dartmouth, this has already happened; ancient novels are part of the reading lists for three courses. "A generation ago, those texts would not have been taught, partly because good translations weren't available, partly because they were not thought to be what classics ought to be like," says Tatum. "They seemed undignified."

Modern translations have made these novels more accessible, but not necessarily any less disturbing for undergraduates with twentieth-century sensibilities. Students generally love Apuleius's Golden Ass, a tale of sex and magic populated with lovely, faithful women, and resourceful, handsome men. However they find Petronius's The Satyricon an entertainment written for Nero's court that includes graphic scenes with boys and eunuchs —"threateningand disgusting."

the study of books by dead authors in dead languages for a dead audience something of a dead end? Not at all, Tatum replies: "Today ancient fiction is one of the liveliest fields in classical and comparative studies." Because researchers have only published a fraction of the total body of work, it's almost as if the novels were still being written. "We are recovering more and more fragments of novels all the time," Tatum says. "Ultimately, I think we shall be in a position to formulate a new and interesting answer to T.S. Eliot's famous question, 'What is a classic?'"

Joni Cole is a student in Dartmouth's Master of Arts in Liberal Studies program. Lee Michaelides is managing editor of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Steady Course

March 1990 By James Wright -

Feature

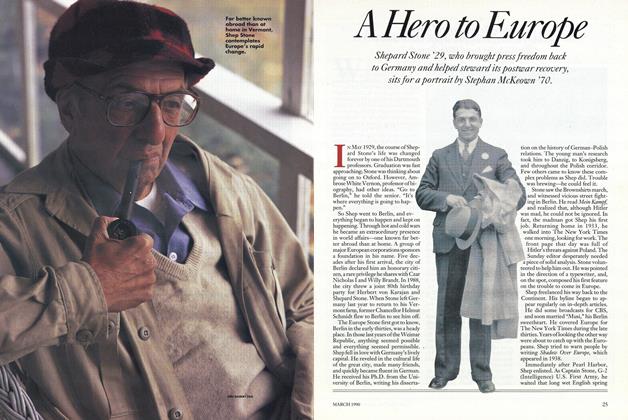

FeatureA Hero to Europe

March 1990 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

March 1990 -

Feature

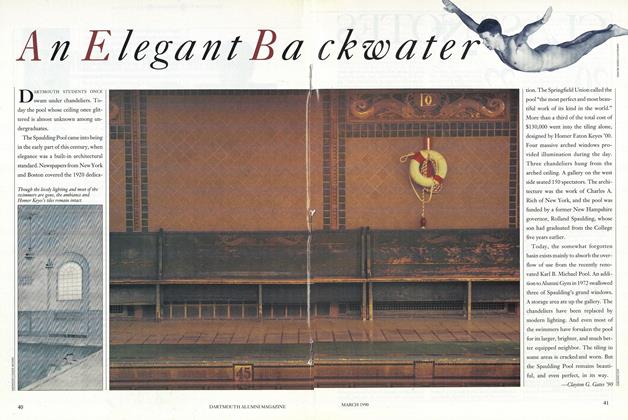

FeatureAn Elegant Backwater

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

March 1990

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

OCTOBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Four

JULY 1967 -

Feature

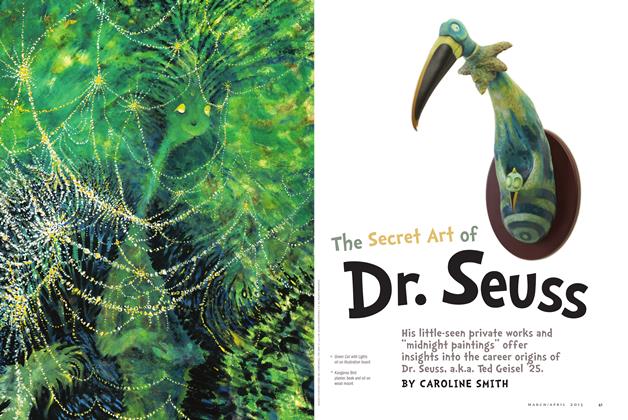

FeatureThe Secret Art of Dr. Seuss

Mar/Apr 2013 By CAROLINE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By HANSON W. BALDWIN -

FEATURE

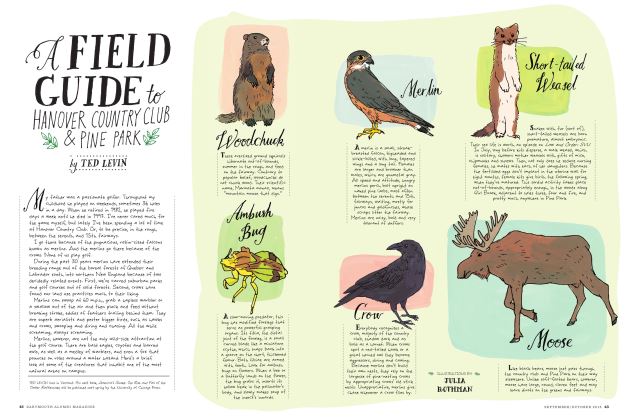

FEATUREA Field Guide to Hanover Country Club & Pine Park

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By TED LEVIN