Ecologist Amory Lovins likes to show people around his "bioshelter," a low-energy-consumption prototype that houses the headquarters of Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI). Its innovative engineering has drawn national attention from the likes of Popular Science, Solar Age, New Shelter, and CBS's "Sixty Minutes."

"This place was built on the principles of ancient Egypt," he says, "with lots and lots of slave labor."

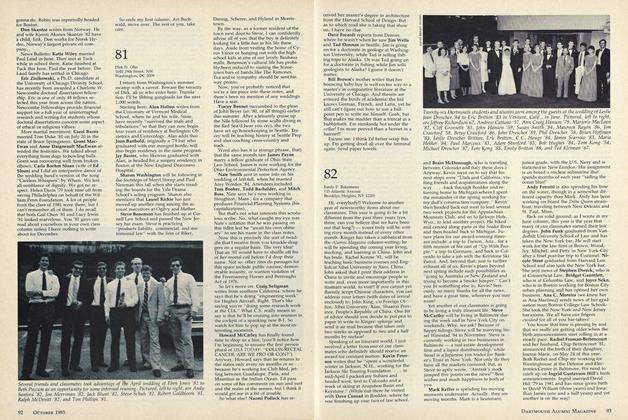

Some of the "slaves" were Dartmouth students and alumni, who with other student volunteers traveled to the Rockies and labored for five months to hand-build the massive stone walls of the structure. Their involvement was an outgrowth of the Lovins' lectures in Hanover in 1982.

During spring quarter Amory Lovins, a physicist-turned-environmental economist, and his wife, Hunter, a lawyer/ecologist, jointly held the Henry B. Luce visiting professorship at Dartmouth. Authors of such works as Brittle Power and Soft Energy Paths, the Lovins were among the first to urge decentralizing America's energy network and seeking alternatives to oil and nuclear power generation.

As environmental consultants to both government and industry, the Lovins had been living out of a suitcase (Amory hadn't had a home address in 11 years). They had decided to establish a headquarters for RMI in Old Snowmass, Colo., and were to begin building right after their stint at Dartmouth. Like the children of Hamlin, Dartmouth Environmental Studies students followed them west.

"I liked Amory and Hunter's style and their content," says Rob Watson '84, who was a sophomore at the time. "I saw a good opportunity to work with some high-powered, intelligent people who were in a field I was interested in. I like working with my hands, and I had the notion of building my own passive solar house some day."

It was idealistic stuff; committed young ecologists hand-building a structure that would be a working example of all that is best in environmental sensitivity. "We got a good lesson in idealism running up against reality," Watson mused.

The building was occupied a year behind schedule, thousands of dollars over budget, and somewhat modified from the original concept. But those who built it agree: It was an incredible learning experience."

The structure is a showcase for respon sible ecological thinking. Winter is tough at 7,100 feet on the West Slope. Snow begins before Thanksgiving and persists into May. Temperatures of 15 degrees below zero aren't exceptional. In this climate the Lovins built a living/work space dependent on passive solar and ambient heat. It has gone through a couple of the hardest winters in Rocky Mountain history, and it looks like it's going to work.

Electric use is one-tenth of normal. Water use is half normal. The heating bill is zero.

"A lot of heart was poured into that house," says Bryant Patten '82, who came to RMI in September 1982, just as crews were finishing the walls of the center section. Patten was surprised to learn when he arrived that Rocky Mountain Institute did not yet exist; he was in on its formation. "It was sort of crazy; RMI was Amory and Hunter, me, and Chris Cappy." (Cappy supervised RMI's work when the Lovins were away on consulting assignments.)

Patten wore a lot of hats: secretary of the Institute, ex officio member of the board of directors, director of the water study - and hauler of concrete. Scrib Fauver '82 and Hal Clifford '83 followed him as interns.

Watson was joined the first summer by Fauver, Nick Lenssen '82, Glenn Grube '82, and Eric Miller, a Colorado College graduate who later came east to Dartmouth's Resource Policy Center. Their main job was handling rock - as in ancient Egypt. With other collegians they quarried dun-colored Dakota sandstone from a site about a mile away (an estimated 150 tons worth), loaded it by hand into a pickup truck, took it to the house site, and fitted it into forms. (The massive rock walls contain a core of polyurethane foam and cement.)

Watson's specialty was sealing the cracks in the insulating core with expanding urethane foam, "the most miserable stuff I've ever had to work with," he recalls. The walls rose about a foot and a half at a time; when one course was dry, the forms were re-set atop it for the next. Where rock shows, the workers had to wash off surplus cement and point up the masonry. It was slow work.

Arriving in June, Watson was in on what he calls "the ongoing evolution of the construction process." Because some of the Lovinses' ideas had never been applied to actual building before (such as the foam core in the slipformed walls), work often halted for discussions about whether technical procedures were feasible.

The Lovinses' basic concept was eventually realized: a comfortable, upscale structure utilizing the best ecologically responsible technologies they knew. It incorporates their living quarters, a subsistence farm indoors, and RMI offices. Central to the 4,000-square-foot building is the greenhouse (Amory calls it "the jungle"), 900 square feet topped by a glass roof sloping to the south. It's designed to double as a solar-heat collector and as a food source producing fish, fruit, nuts, and vegetables in a closed ecosystem.

Technological innovations in the house are numerous enough that the Lovinses have produced a lb-page guide to explain them all. (Perhaps most astonishing are windows that admit solar heat but do not allow it to exit.)

There's also a Where-To-Get-It sheet for people wanting to use some of the new technologies in their own structures. Both can be requested by mail ($2, RMI, Box 248, Old Snowmass CO 81654). The staff will give tours during business hours, but they ask visitors to call ahead: 303/927-3851.

What's the first item seen on the tour? It's a brass plaque in the rock-walled entryway, memorializing the student volunteer builders.

MARTY CARLOCK

Marty Carlock is a free-lance writer who specializes in art and architecture.

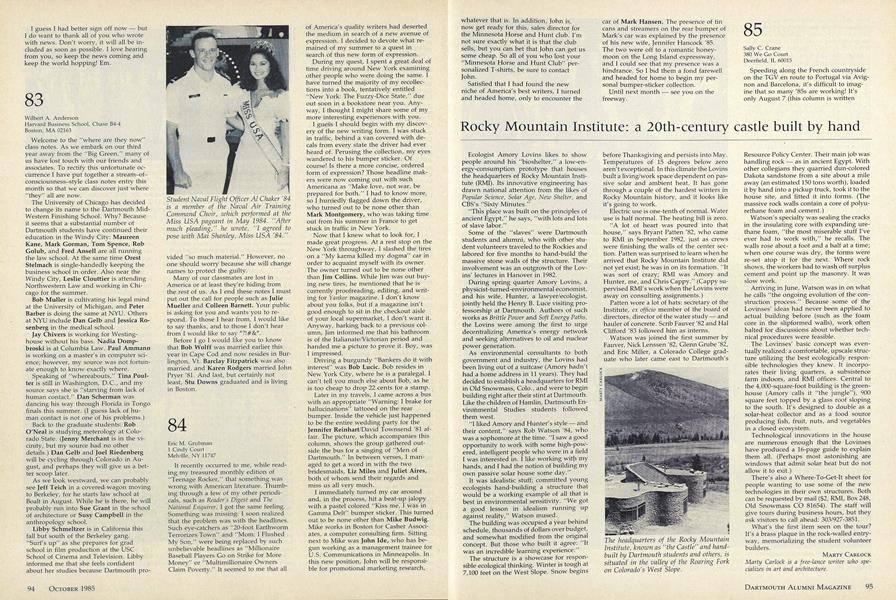

The headquarters of the Rocky MountainInstitute, known as "the Castle" and handbuilt by Dartmouth students and others, issituated in the valley of the Roaring Forkon Colorado's West Slope.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

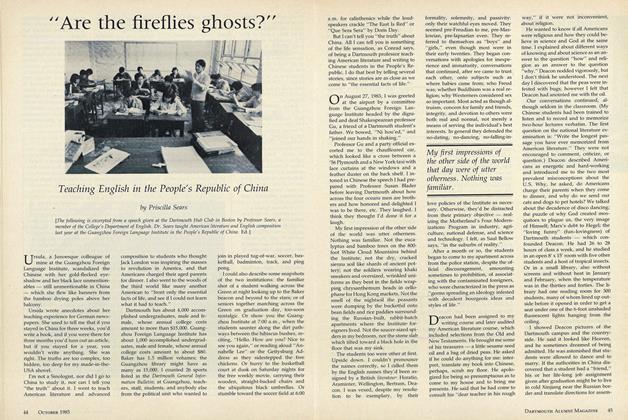

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

October 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Article

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

October 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsOn the road to Cambridge. The Harvard Game

October 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

October 1985 By Burr Gray -

Article

ArticleThomas V. Seessel '59: "It's okay to say 'No' "

October 1985 By Rex Roberts -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1985 By Emily P. Bakemeier