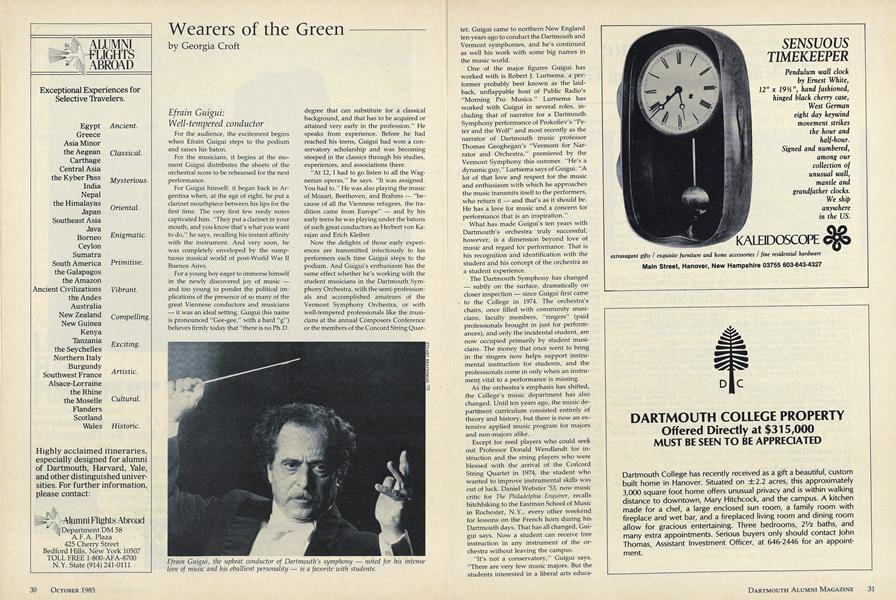

For the audience, the excitement begins when Efrain Guigui steps to the podium and raises his baton.

For the musicians, it begins at the moment Guigui distributes the sheets of the orchestral score to be rehearsed for the next performance.

For Guigui himself, it began back in Argentina when, at the age of eight, he put a clarinet mouthpiece between his lips for the first time. The very first few reedy notes captivated him. "They put a clarinet in your mouth, and you know that's what you want to do," he says, recalling his instant affinity with the instrument. And very soon, he was completely enveloped by the sumptuous musical world of post-World War II Buenos Aires.

For a young boy eager to immerse himself in the newly discovered joy of music and too young to ponder the political implications of the presence of so many of the great Viennese conductors and musicians - it was an ideal setting. Guigui (his name is pronounced "Gee-gee," with a hard "g") believes firmly today that "there is no Ph.D. degree that can substitute for a classical background, and that has to be acquired or attained very early in the profession." He speaks from experience. Before he had reached his teens, Guigui had won a conservatory scholarship and was becoming steeped in the classics through his studies, experiences, and associations there.

"At 12, I had to go listen to all the Wagnerian operas," he says. "It was assigned. You had to." He was also playing the music of Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms - "because of all the Viennese refugees, the tradition came from Europe" and by his early teens he was playing under the batons of such great conductors as Herbert von Karajan and Erich Kleiber.

Now the delights of those early experiences are transmitted infectiously to his performers each time Guigui steps to the podium. And Guigui's enthusiasm has the same effect whether he's working with the student musicians in the Dartmouth Symphony Orchestra, with the semi-professionals and accomplished amateurs of the Vermont Symphony Orchestra, or with well-tempered professionals like the musicians at the annual Composers Conference or the members of the Concord String Quartet. Guigui came to northern New England ten years ago to conduct the Dartmouth and Vermont symphonies, and he's continued as well his work with some big names in the music world.

One of the major figures Guigui has worked with is Robert J. Lurtsema, a performer probably best known as the laidback, unflappable host of Public Radio's "Morning Pro Musica." Lurtsema has worked with Guigui in several roles, including that of narrator for a Dartmouth Symphony performance of Prokofiev's "Peter and the Wolf" and most recently as the narrator of Dartmouth music professor Thomas Geoghegan's "Vermont for Narrator and Orchestra," premiered by the Vermont Symphony this summer. "He's a dynamic guy," Lurtsema says of Guigui. "A lot of that love and respect for the music and enthusiasm with which he approaches the music transmits itself to the performers, who return it and that's as it should be. He has a love for music and a concern for performance that is an inspiration."

What has made Guigui's ten years with Dartmouth's orchestra truly successful, however, is a dimension beyond love of music and regard for performance. That is his recognition and identification with the student and his concept of the orchestra as a student experience.

The Dartmouth Symphony has changed -subtly on the surface, dramatically on closer inspection since Guigui first came to the College in 1974. The orchestra's chairs, once filled with community musicians, faculty members, "ringers" (paid professionals brought in just for performances), and only the incidental student, are now occupied primarily by student musicians. The money that once went to bring in the ringers now helps support instrumental instruction for students, and the professionals come in only when an instrument vital to a performance is missing.

As the orchestra's emphasis has shifted, the College's music department has also changed. Until ten years ago, the music department curriculum consisted entirely of theory and history, but there is now an extensive applied music program for majors and non-majors alike.

Except for reed players who could seek out Professor Donald Wendlandt for instruction and the string players who were blessed with the arrival of the Concord String Quartet in 1974, the student who wanted to improve instrumental skills was out of luck. Daniel Webster '53, now music critic for The Philadelphia Enquirer, recalls hitchhiking to the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., every other weekend for lessons on the French horn during his Dartmouth days. That has all changed, Guigui says. Now a student can receive free instruction in any instrument of the orchestra without leaving the campus.

"It's not a conservatory," Guigui says. "There are very few music majors. But the students interested in a liberal arts education like to come here for music as part of that. There are a number of highly motivated, dedicated students who have always made it possible to achieve an almost professional level of performance with every concert."

Concord Quartet cellist Norman Fischer says it's Guigui's ability to inspire students to perform while never forgetting that they are students that has made his tenure at Dartmouth so successful. "The most amazing thing about Guigui and the way he works with the Dartmouth Symphony is that a tremendous amount of fire and

energy go along with the Latin temperament; yet at the same time he is very understanding and realistic about the students about what the Dartmouth Symphony is. He is realistic without selling out. He recognizes that for most of the students, playing in the symphony is just one of the things they do as part of being at Dartmouth, but he keeps their interest by challenging them and yet doesn't challenge them so much that it discourages them."

Part of achieving that balance is making sure the students have the opportunity at least once in every four-year cycle to play the great classics they want to experience - such as Beethoven's Fifth and Ninth symphonies while enlivening the repertoire and the musical experience by also exposing the students ,to contemporary works. A performance of a work such as Beethoven's Ninth this past spring "gets everyone all fired up and excited and draws everything right out of them," Fischer says. Guigui himself looks back on that performance as "sort of a climateric to my ten years of being here."

But it's with equal gratification that Guigui assesses his program of bringing contemporary composers to the campus to lecture and work with the students in preparation for performances of their music. "This is a very exciting learning experience for members of the orchestra," Guigui says. Among the composers who have briefly taken up residency on campus is Hector Compos Parsi of Puerto Rico. "The regular Latin rhythms of his music made a very good learning experience for the students," Guigui says, "and this year, we'll have Bernard Rands, the 1983 Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, in residence for a week or two."

His work with contemporary music ft the forte that has brought Guigui into prominence as a conductor. That commitment was nourished by an early friendship with composer Aaron Copland, at whose invitation Guigui initially left his home in Argentina and eventually made his conducting debut in 1964 at Carnegie Hall in a concert of new music. "Contemporary music is a mission, a challenge," Guigui says. "Look at Bach in his time. The churchgoers wrote a letter that he should be fired after he began developing chromatic harmonies. Neither Beethoven nor Wagner could have existed without him and his work with chromatic harmonies. If we were to ignore the contemporary composer, we might be ignoring a Bach or a Beethoven or a Chopin."

Guigui sees himself as "an interpreter, a medium" between the composer and the audience and as such has conducted the works of new composers every summer for 18 years at the prestigious Composers Conference, held annually at Wellesley College under the leadership of Mario Davidovsky. His work there and with pieces commissioned for other groups and performers has won him a wide reputation for remarkably quick and accurate interpretations.

Dartmouth's Geoghegan, whose "Vermont for Narrator and Orchestra" was commissioned for the Vermont Symphony's 50th anniversary year and was premiered under Guigui's baton this past summer, says Guigui has "an unerring ability to always be able to know instinctively what a piece should sound like regardless of its style. He just zeroes in instinctively, whether the piece is contemporary or conservative." Watching the first run-through of his own piece with the Vermont Symphony players, Geoghegan says he was astounded to see the conductor "solfegging

- singing in the parts of all the instruments that were not there. It was amazing to see him do that with such rapidity."

"Vermont for Narrator and Orchestra" is a piece that Guigui hopes may win the Vermont Symphony an invitation to perform at the White House as the climax to the orchestra's anniversary. The VSO has already achieved national recognition for its "251 series" of concerts small ensembles from the orchestra traveling to perform in every one of Vermont's 251 towns during the two-year celebration - and Guigui hopes the theme of Geoghegan's piece may attract the interest of the White House Staff.

"It's based on a speech by Calvin Coolidge while he was president, but it's nonpolitical," Guigui explains. "It was in 1927 when there were the terrible floods, and Coolidge came back to Vermont to see the damage. The train stopped in Bennington, and he was so moved by what he saw, by the disaster, that Silent Cal broke his silence and got out and made this speech. Geoghegan based the music on the Vermont vernacular it's a folk type of melody. Who knows. It might get us to the White House. Coolidge is a natural for that sort of thing."

If Guigui and the Vermont Symphony do go to Washington, traveling with them will be orchestra manager Morris Block '79 who arrived at Dartmouth shortly after Guigui and has been influenced by him ever since.

"I came to Dartmouth as a Russian major and also did pre-med," Block says, "but I spent my whole time doing music. Guigui was new at that point. There was a great feeling among the sudents great excitement and enthusiasm from working under him." As a cellist, Block became a member of the orchestra and two months later also became its manager. Once Block became involved, he became totally involved. He performed, he managed, he started a chamber orchestra, and he helped get the College's operatic production of The Merry Wives ofWindsor under way.

"Working with Guigui shaped my whole experience at Dartmouth," Block says. "I took one music course all the time I was there, but I got the music award at graduation because of all the things I did, and a lot of that was due to Guigui. He conveys excitement and enthusiasm. There are people with bigger orchestras and bigger musicians who don't impart the knowledge of music that Guigui does from the podium."

Block gave up his idea of a career in medicine and went on to become the manager of a large chamber orchestra on Long Island before joining the Vermont Symphony four years ago. Together - Block on the cello, Guigui on the clarinet - the two occasionally perform for benefits and for such gala events as Vermont Governor Madeleine Kunin's inauguration. Together they've also worked to rebuild the VSO.

They speak with open admiration of each other's accomplishments. "We've really built the Vermont Symphony," Block says. "Guigui has built the artistic quality of the orchestra. It all comes from the podium. The orchestra was not playing well and was in financial difficulty."

Guigui is even more blunt in his assessment. "The orchestra was nearly bankrupt - financially and artistically," he says. "In four years, Morris has done an excellent job to the point where he now has doubled the Vermont Symphony's budget to $600,000."

And Guigui sees Block's history repeating itself in the experiences of Claudia Leis, the current manager of the Dartmouth Symphony and the first woman manager in the orchestra's history. "She is the most efficient manager we've ever had, and here again, it seems that the bug has bit her," Guigui says. "She is changing from a history major to an arts management major."

While Guigui is most often cited by those who have worked with him for the enthusiasm and excitement he conveys through his approach to music, he also conveys a quieter but complete contentment with the New England lifestyle he has adopted.

Guigui came to Vermont from Puerto Rico where he was working for the Casals Festival and teaching at the Casals Conservatory. At first, he says, he thought he had made an admirable sacrifice of salary and tenure to come to rescue two flagging orchestras. "It didn't last too long, that feeling of being proud of giving up tenure and taking a salary cut to come to Vermont. I found out soon that everyone else did it, too, because the quality of life and the people are so wonderful. And Dartmouth College and the Hopkins Center are very special places. I'm very privileged to be able to function here."

Efrain Guigui, the upbeat conductor of Dartmouth's symphony-noted for his intenselove of music and his ebullient personality-is a favorite with students.

Georgia Croft writes frequently on the arts atDartmouth and in the Upper Valley.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

October 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Sports

SportsOn the road to Cambridge. The Harvard Game

October 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

October 1985 By Burr Gray -

Article

ArticleThomas V. Seessel '59: "It's okay to say 'No' "

October 1985 By Rex Roberts -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1985 By Emily P. Bakemeier -

Article

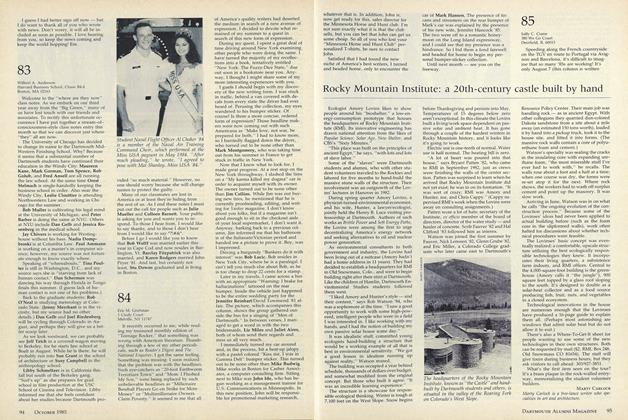

ArticleRocky Mountain Institute: a 20th-century castle built by hand

October 1985

Georgia Croft

-

Article

ArticleFriend of the media

MAY 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

MARCH • 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleGil Fernandez '33: a fine friend to the feathered

MAY 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

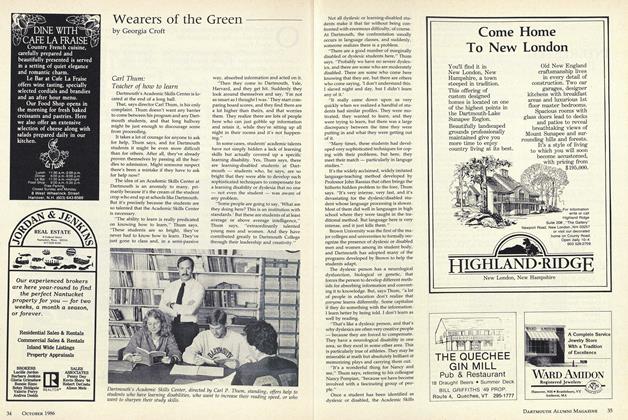

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

OCTOBER • 1986 By Georgia Croft

Article

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Night

November 1943 -

Article

ArticleTim Ellis Memorial Fund

February 1956 -

Article

ArticleEven the Professors

JANUARY, 1928 By "F. Clark S. '30." -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

AUGUST 1930 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleTRACK

MAY 1963 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22