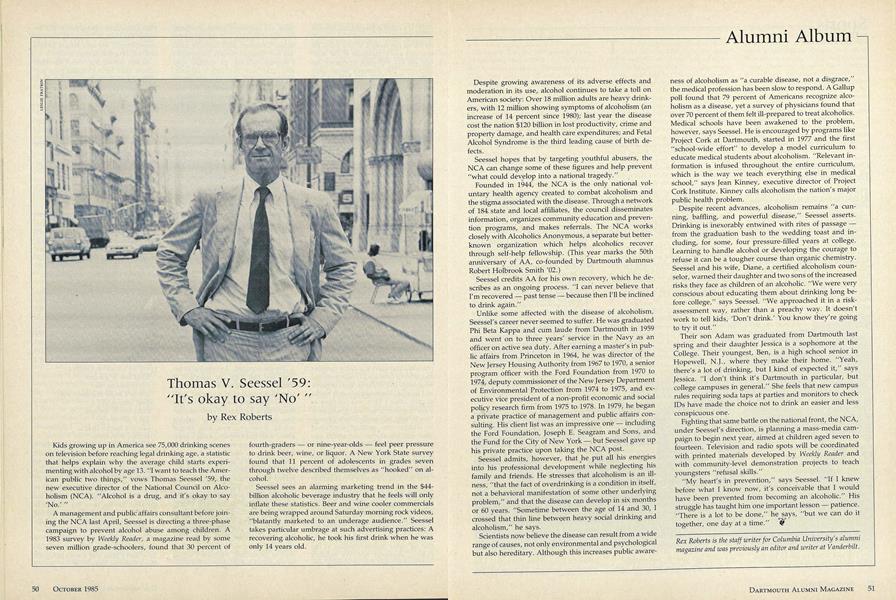

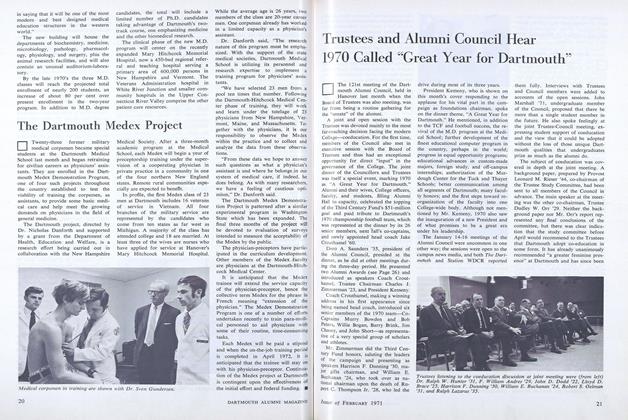

Kids growing up in America see 75,000 drinking scenes on television before reaching legal drinking age, a statistic that helps explain why the average child starts experimenting with alcohol by age 13. "I want to teach the American public two things," vows Thomas Seessel '59, the new executive director of the National Council on Alcoholism (NCA). "Alcohol is a drug, and it's okay to say 'No.' "

A management and public affairs consultant before joining the NCA last April, Seessel is directing a three-phase campaign to prevent alcohol abuse among children. A 1983 survey by Weekly Reader, a magazine read by some seven million grade-schoolers, found that 30 percent of fourth-graders - or nine-year-olds feel peer pressure to drink beer, wine, or liquor. A New York State survey found that 11 percent of adolescents in grades seven through twelve described themselves as "hooked" on alcohol.

Seessel sees an alarming marketing trend in the $44- billion alcoholic beverage industry that he feels will only inflate these statistics. Beer and wine cooler commercials are being wrapped around Saturday morning rock videos, "blatantly marketed to an underage audience." Seessel takes particular umbrage at such advertising practices: A recovering alcoholic, he took his first drink when he was only 14 years old.

Despite growing awareness of its adverse effects and moderation in its use, alcohol continues to take a toll on American society: Over 18 million adults are heavy drinkers, with 12 million showing symptoms of alcoholism (an increase of 14 percent since 1980); last year the disease cost the nation $120 billion in lost productivity, crime and property damage, and health care expenditures; and Fetal Alcohol Syndrome is the third leading cause of birth defects.

Seessel hopes that by targeting youthful abusers, the NCA can change some of these figures and help prevent "what could develop into a national tragedy."

Founded in 1944, the NCA is the only national voluntary health agency created to combat alcoholism and the stigma associated with the disease. Through a network of 184. state and local affiliates, the council disseminates information, organizes community education and prevention programs, and makes referrals. The NCA works closely with Alcoholics Anonymous, a separate but better- known organization which helps alcoholics recover through self-help fellowship. (This year marks the 50th anniversary of AA, co-founded by Dartmouth alumnus Robert Holbrook Smith '02.)

Seessel credits AA for his own recovery, which he describes as an ongoing process. "I can never believe that I'm recovered past tense - because then I'll be inclined to drink again."

Unlike some affected with the disease of alcoholism, Seessel's career never seemed to suffer. He was graduated Phi Beta Kappa and cum laude from Dartmouth in 1959 and went on to three years' service in the Navy as an officer on active sea duty. After earning a master's in public affairs from Princeton in 1964, he was director of the New Jersey Housing Authority from 1967 to 1970, a senior program officer with the Ford Foundation from 1970 to 1974, deputy commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection from 1974 to 1975, and executive vice president of a non-profit economic and social policy research firm from 1975 to 1978. In 1979, he began a private practice of management and public affairs consulting. His client list was an impressive one - including the Ford Foundation, Joseph E. Seagram and Sons, and the Fund for the City of New York but Seessel gave up his private practice upon taking the NCA post.

Seessel admits, however, that he put all his energies into his professional development while neglecting his family and friends. He stresses that alcoholism is an illness, "that the fact of overdrinking is a condition in itself, not a behavioral manifestation of some other underlying problem," and that the disease can develop in six months or 60 years. "Sometime between the age of 14 and 30, I crossed that thin line between heavy social drinking and alcoholism," he says.

Scientists now believe the disease can result from a wide range of causes, not only environmental and psychological but also hereditary. Although this increases public awareness of alcoholism as "a curable disease, not a disgrace, the medical profession has been slow to respond. A Gallup poll found that 79 percent of Americans recognize alcoholism as a disease, yet a survey of physicians found that over 70 percent of them felt ill-prepared to treat alcoholics. Medical schools have been awakened to the problem, however, says Seessel. He is encouraged by programs like Project Cork at Dartmouth, started in 1977 and the first "school-wide effort" to develop a model curriculum to educate medical students about alcoholism. "Relevant information is infused throughout the entire curriculum, which is the way we teach everything else in medical school," says Jean Kinney, executive director of Project Cork Institute. Kinney calls alcoholism the nation's major public health problem.

Despite recent advances, alcoholism remains "a cunning, baffling, and powerful disease," Seessel asserts. Drinking is inexorably entwined with rites of passage - from the graduation bash to the wedding toast and including, for some, four pressure-filled years at college. Learning to handle alcohol or developing the courage to refuse it can be a tougher course than organic chemistry. Seessel and his wife, Diane, a certified alcoholism counselor, warned their daughter and two sons of the increased risks they face as children of an alcoholic. "We were very conscious about educating them about drinking long before college," says Seessel. "We approached it in a riskassessment way, rather than a preachy way. It doesn't work to tell kids, 'Don't drink.' You know they're going to try it out."

Their son Adam was graduated from Dartmouth last spring and their daughter Jessica is a sophomore at the College. Their youngest, Ben, is a high school senior in Hopewell, N.J., where they make their home. "Yeah, there's a lot of drinking, but I kind of expected it," says Jessica. "I don't think it's Dartmouth in particular, but college campuses in general." She feels that new campus rules requiring soda taps at parties and monitors to check IDs have made the choice not to drink an easier and less

conspicuous one. Fighting that same battle on the national front, the NCA, under Seessel's direction, is planning a mass-media campaign to begin next year, aimed at children aged seven to fourteen. Television and radio spots will be coordinated with printed materials developed by Weekly Reader and with community-level demonstration projects to teach youngsters "refusal skills."

"My heart's in prevention," says Seessel. "If I knew before what I know now, it's conceivable that I would have been prevented from becoming an alcoholic." His struggle has taught him one important lesson patience. "There is a lot to be done," he says, "but we can do it together, one day at a time."

Rex Roberts is the staff writer for Columbia University's alumnimagazine and was previously an editor and writer at Vanderbilt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

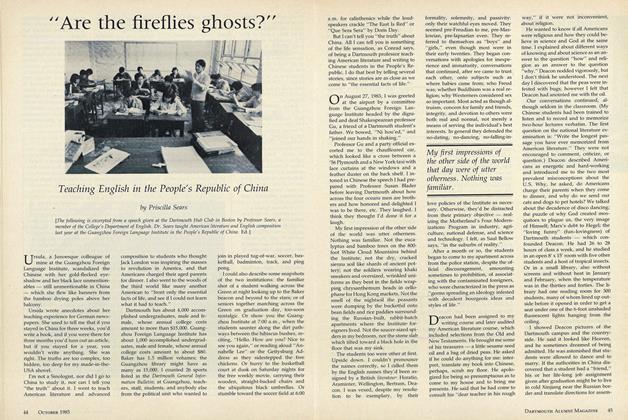

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

October 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Article

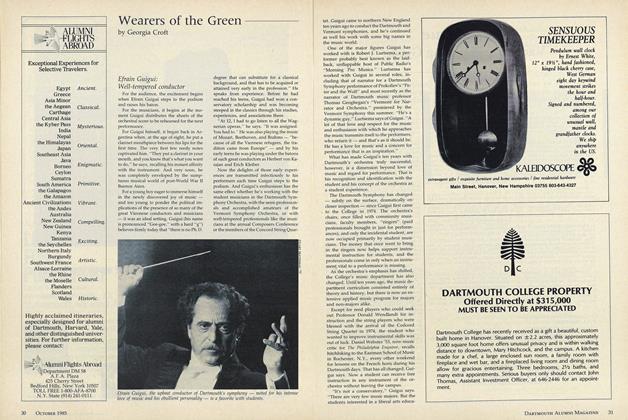

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

October 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsOn the road to Cambridge. The Harvard Game

October 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

October 1985 By Burr Gray -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1985 By Emily P. Bakemeier -

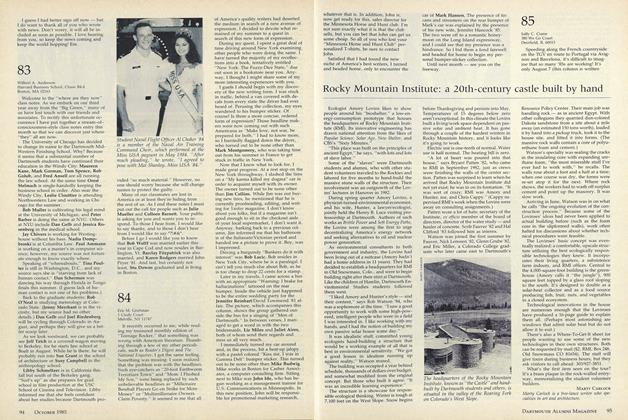

Article

ArticleRocky Mountain Institute: a 20th-century castle built by hand

October 1985