Are smiles more importantthan issues?

Four Dartmouth professors seek some answers

Political pundits have long contended that the introduction of television into the American electoral machinery permanently altered the way we choose our leaders, but few have studied the medium and its political effects as rigorously as has a group of Dartmouth professors.

Four Dartmouth faculty members:— Denis Sullivan and Roger Masters of the government department and John Lanzetta and Greg McHugo of the psychology department - have spent the last three years investigating the ways people communicate non-verbal messages to one another. Their overlapping interests led them into politics, where leaders' facial displays may profoundly affect voting decisions.

"I think a lot of politicians make the mistake of thinking that people care," McHugo says. Whereas political candidates often direct their campaign activities toward communicating issue positions and rational reasons for voters to back them, a candidate's success may be more contingent on his or her ability to elicit emotional responses from the television audience. And the politician's facial expressions and other non-verbal cues may lie at the heart of that ability.

McHugo's insights into the political process underscore some of the premises of the Dartmouth Committee for the Experimental Study of Social and Political Behavior, as the four major collaborators in this extended study are known. By running a series of experiments on Darmouth students and alumni, the group has tested ideas about how our perceptions of politicians on television may stem from deeply-rooted primal responses to facial expressions.

Our reactions to a smile particularly seem to touch an area of human perception that affects us at a sub-conscious level, a level we share with other primates. "Smiles are just gopd things," Lanzetta says. He calls a subject's reaction to a smile "a primitive response." When people see smiling faces, they relax and they may become more receptive to the ideas they're hearing.

Sullivan recognized some of the political implications of facial display in a television era, and he knew of some of his colleagues' research in related areas. He had read some of Lanzetta's work in experimental psychology and had discussed Masters's interest in ethology (the study of animal behaviors). In early 1982, Sullivan brought the two together in a study that combined their interests with his own, American politics.

"I suppose it was my idea," Sullivan says. "Roger and I had tried a few things out, and I had read Lanzetta's work. I thought we had a common ground."

After discussing their common interests in studying facial displays of political leaders, the three invited McHugo, a postdoctoral student at the time, to join the project.

Over the three-year period of the project, the four have established an informal division of labor, with Sullivan and Masters providing most of the background in political science theories and Lanzetta and McHugo contributing their expertise in facial display behavior and in running social science experiments. "Most of the laboratory stuff people in political science aren't very well trained for. On the other hand, the political science theories have to come from them," Lanzetta notes. "We complement each other very well."

By conducting research in an area that involves so many disciplines, the project has opened up chances for many students doing honors research to work closely with the project directors. That, according to Sullivan, has proved one of the most rewarding aspects of the study.

"I don't think too many people appreciate the importance of student-faculty cooperation," Sullivan says. In addition to his work with the project, Sullivan teaches a seminar on media and politics. Three government majors this year wrote theses that examined television's role in the political process; all of them had previously taken Sullivan's seminar.

The fusion of disciplines also leads to articles and papers that are often neglected in more traditional research. But while the project's interdisciplinary focus occasionally creates problems in seeking out interested publications, McHugo thinks that overall it has benefited them.

The project's early days were occupied with laying the theoretical foundations of the research and securing grant money to pursue it. The original money for the work came from the College, but the group quickly turned to outside sources for support. At the beginning, the project's members were primarily concerned with writing grant applications, McHugo said.

But soon the actual work got under way. The group ran its first experiment in the summer of 1982, using Alumni College students and their families as research subjects. These early experiments established several important bases upon which much of the group's subsequent research has built. They demonstrated that viewers were remarkably adept at identifying television displays. And they suggested that some media were more effective than others at communicating given emotions; "voice-only," for instance, proved the most capable of eliciting subjects' sense of inspiration, while "image-only" was most effective in evoking joy.

These early studies also suggested that subjects drew a distinction, whether conscious or not, between their descriptions of the political behavior they viewed and their responses to that behavior. Descriptions tended to be consistent for all viewers, regardless of their feelings about the politician viewed, but emotional response answers were more volatile.

"Unlike descriptions . . . ," Masters writes in one paper, "these emotional responses are strongly influenced by prior attitudes - and, in general, show that changes in facial display have a larger effect on the emotional responses of supporters than of critics."

Many of the group's experiments have used clips of Ronald Reagan to evaluate the ways viewers perceive facial displays. As a result, the project members have had ample chance to observe the president's ability to communicate to television viewers. Not surprisingly for a politician sometimes called "The Great Communicator," Reagan appears to elicit strong, and sometimes even unwitting, responses from experimental subjects.

Lanzetta notes that "even subjects who don't like him find themselves smiling along with him." As McHugo points out, "that's Ronald Reagan the consummate actor. There's . . . coherence to [his behavior]." McHugo adds, though, that other politicians may not be able to duplicate Reagan's ability to elicit emotion in viewers.

But while Reagan has generated strong responses from many subjects, the project's members are less convinced of the president's ability to dominate the medium. "Being a president is somewhat like being an actor," Sullivan states. "He's better than Carter or Ford, much better than Mondale, but it's not clear to me that he is better than, say, Kennedy or Roosevelt."

McHugo points out the president's ability to sidestep criticism for his often controversial issue positions, but he still cautions against overemphasizing Reagan's image. "He can take issue positions that you think are outrageous, and you still think he's a nice guy. . . I don't think he's a great actor, but in the right role he's unbeatable. I do think Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda could play it just as well," he says.

Sullivan tends to disparage the often-expressed opinion that Reagan has revolutionized the televised presidency. Much of Reagan's success, Sullivan notes, can be attributed to the relative weakness of the opponents he has faced. "Reagan ran against two people who were very poor in their use of media," he says.

Also, Sullivan points out that some of Reagan's success may be more a factor of his ability to use the office of the presidency. Whereas Reagan as an incumbent has appeared invincible, "Reagan as a challenger was so-so," Sullivan states.

Having used Reagan for so many of its early studies, the group later turned to the Democratic candidates in last year's presidential race in order to look at how viewers respond to less well-known figures and to study how viewers' feelings change in response to shifts in the relative status of the candidates they watch.

To gather material for this and possible future studies, the project members hired several students and a video technician to create an archive of campaign footage. These people culled every network news show - morning, mid-day, and evening - as well as PBS newscasts such as the "MacNeil-Lehrer Report" in order to seek out clips of candidates exhibiting each of the three major categories of facial display: anger/threat, happy/reassurance, and fear/evasion. Virtually the entire presidential campaign is now logged in the archive, providing the potential for extensive research, either by historians interested in general aspects of the campaign coverage or by others interested in more specific features.

The group used clips of each candidate, along with shots of some lesser-known American political figures, to elicit responses from student subjects and to compare reactions in January with those in October, when the field had narrowed and realigned.

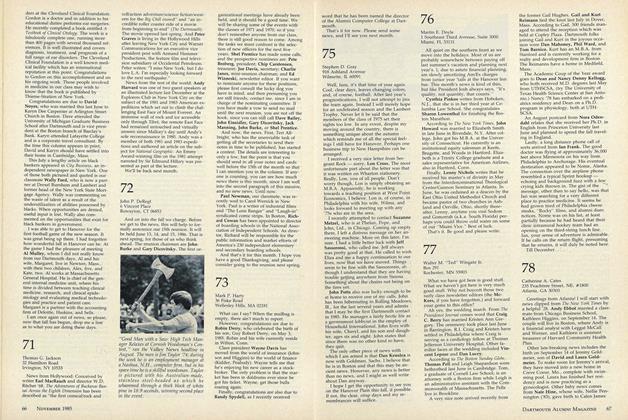

The results illuminate the candidates' strengths and weaknesses in mastering television. Perhaps most significantly, from the historical perspective, are the findings on Walter Mondale. Mondale was very issue-oriented, according to McHugo. "I'm not sure that's very effective," he says.

Masters points out that even in Mondale' s most smiling, emotionally evocative moments, he never came close to Reagan's ability to elicit a positive response from viewers. Moreover, virtually all the clips of Mondale show him with so-called "neutral" facial expressions, those which do not convey any particular emotion.

By contrast, Jesse Jackson easily conveys the whole range of emotional displays, though Sullivan notes that may not have always worked to his advantage. "Jesse Jackson is very evocative," he says. "He produced a large effect, but it was not always positive."

McHugo attributes the tremendous volume of media coverage that Jackson received to his willingness to go in front of the camera in relatively unstructured formats. Whereas Jackson regularly appeared on the news shows, Mondale avoided them as much as possible. McHugo says two factors contributed to that divergence in campaign styles: First, "Jackson knew that he had nothing to lose," McHugo states; and second, "Jackson knew he was a media candidate. Mondale knew he was not."

The candidate who elicited some of the most interesting results of the Democratic lineup was Gary Hart. Unlike Jackson, Hart rarely displayed intense anger/threat over the course of the campaign, but his smile evoked positive feelings in those who saw it.

"His smile is reasonably evocative," Sullivan says. Masters also emphasizes Hart's effectiveness on television, noting that his comfort with the medium might have made him a more difficult contender for Reagan to battle in the general election.

The members of the project hesitate when asked to discuss the implications for the politician hoping to use their findings to manipulate voters. Their most common reaction, however, is that viewers are too sensitive to false displays to be taken in by a politician who tries to force a smile at every public appearance.

Lanzetta acknowledges that politicians attempt to structure their behavior in order to impress voters, but he also notes that voters are "well aware that the behavior they are seeing is for their benefit." McHugo agrees, saying that people tend to watch politicians while thinking to themselves, "This person is trying to persuade me."

Sullivan is less certain that the findings about emotional response might not be of some use to aspiring candidates, but he does reject the notion that its use would be a simple matter. "I don't think there's an easy answer," he says. "There's no recipe for emotions, and a person can't pretend to be something he isn't."

"Bad acting is obvious," McHugo asserts.

Where the group goes with its study is uncertain. Masters is in Paris for the year pursuing other research. The project's future to some extent may depend on his enthusiasm for continuing his work with the committee when he gets back to Hanover.

Perhaps even more important is the members' sense that they have accomplished what they set out to do. The project has changed somewhat over the years it has developed, McHugo says, but it has addressed each of the issues its members originally set forth.

"We pretty much knew what we were going to do for the next couple of years when we first sat down," he says.

The group will complete at least one more study this fall, according to Lanzetta. After that, "it's unclear what future it has," Sullivan states.

For the time being, the members are wrapping up work on a chapter for a new book, and they are studying the interaction between emotion and cognitive recall more thoroughly; in other words, they are looking at the implications of subjects' emotional state on their ability to retain the content of what they have seen and heard. That focus begins to move the project away from some of its grounding in political science and more towards a purely psychological base.

Clearly, the group has proven that it can generate theoretically interesting, methodologically rigorous research. That alone has insured it future funding and has accorded it some status within the academic community. Academic journals have published some of the group's research, and more popular magazines, including Time and Psychology Today, have reported on the group's work.

The project's success in attracting funds, attention, and interested students may convince its members to continue pursuing what they have demonstrated is a fertile area for research.

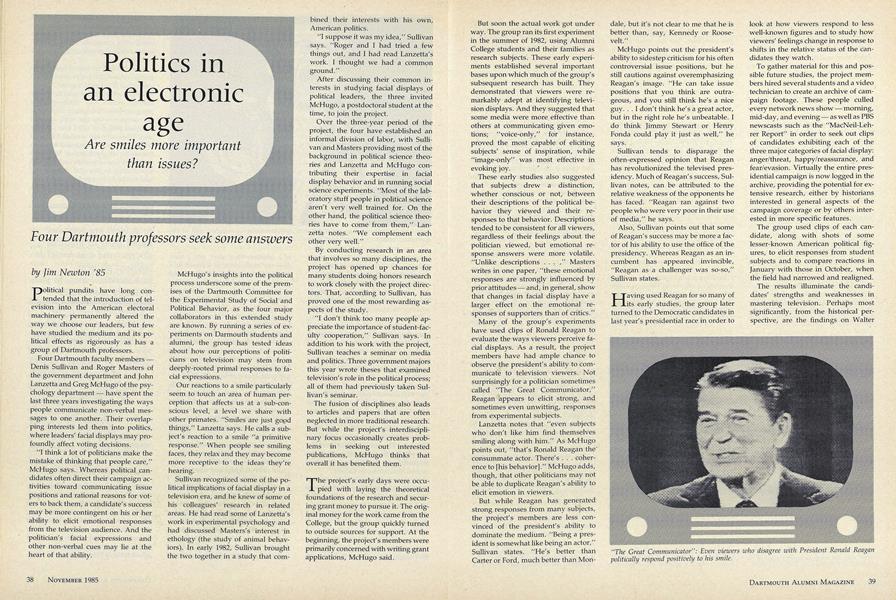

"The Great Communicator Even viewers who disagree with President Ronald Reaganpolitically respond positively to his smile.

Democratic challenger Walter Mondale's predominantly "neutral" facial expression, however, does not evoke as much emotional reaction from viewers.

Jim Newton, publisher of The Dartmouth last year, was one of the "interested students" who worked with members of theproject. He is currently a clerk for JamesReston in the Washiiigtoji bureau of The New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Man for All Seasons

November 1985 By Douglas McCreary Greenwood '66 -

Feature

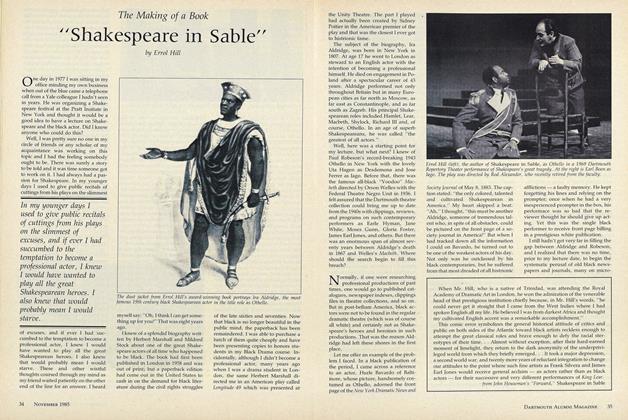

Feature"Shakespeare in Sable"

November 1985 By Errol Hill -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

November 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

November 1985 By Catherine A. Gates -

Sports

SportsTough days on the gridiron

November 1985 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

November 1985 By Bruce D. Jolly

Jim Newton '85

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSports Style-Setter

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureHEAR ON THE STREET

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureADRIAN W.B. RANDOLPH

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE SPIRIT OF ADVENTURE

Jan/Feb 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Feature

FeatureManin the Red Flannel shirt

January 1974 By M.B.R.