HANS DELBRUCK & THE GERMAN MILITARY ESTABLISHMENT

by Arden Bucholz '5BUniversity of lowa Press, 1985224 pp., $20.00

Perhaps the central event of European history during the last half of the nineteenth century was the political realization of what was, economically, an accomplished fact - the unification of Germany - and the subsequent glorification of the Prussian military apparatus that brought it about. The institution of the officers corps as an elite aristocracy, coupled with the heady successes enjoyed by the military under the strategic and political guidance of von Moltke and Bismarck, brought about a near institutionalization of a military mentality that affected the world for the next eighty years.

That same success, however, also fostered a split in the study of military science that its progenitors and canonized saints Clausewitz, Frederick the Great, even von Moltke and Bismarck - might have found difficult to swallow. Under the General Staff, military science became the study of the battlefield strategy and tactics. To the academicians of the university were left the political causes and consequences of war. No one sat in the middle to weave the strands together and the result was a warped interpretation both of the great engagements of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and of the strategic thinking of, particularly, Frederick the Great.

Hans Delbruck was one person who tried, arguing, for instance, to deaf ears that Frederick's strategic "war of annihilation" - so heartily embraced by the General Staff and von Schlieffen - was only part of a much more pragmatic philosophy geared towards only enough war to achieve the advantage needed to gain one's political ends. This first skirmish marked Delbruck at once as an original and thoughtful military commentator, and as an outsider at odds with both branches of the military "establishment" - the officer corps and the university. The ensuing years would see him pitted against them time and time again, right through the disastrous campaigns of the First World War when his grave misgivings about courses of action were muted by the moral-boasting necessity of maintaining a united public front, and the post-war interpretations of the conflict which were warped by the rising Nazi party to its own advantage.

Delbruck's approach to the study of war

- as a synthesis of social, political, military, and technological forces - hardly seems novel, but in the heightened militaristic atmosphere of turn-of-the-century Germany, it ran contrary to vested military interests. It would be easy to portray Delbriick as an unheeded Cassandra whose pronouncements, if followed, would have saved the course of his country's history. He might be the first to admit, however, that historical forces too often take on a life beyond the ability of one man to effect. Arden Bucholz, whose study puts those forces in perspective, offers an account of Delbruck's scholarly life and thought that is at once clear and insightful, and of interest both to the casual historian and the professional military scientist. The professional will already have steeped himself in Delbruck's landmark treatises, but Bucholz's account of Delbruck's own battles against entrenched interests that kept his work in nearly lifelong discredit is a fascinating and instructive story, a valuable addition to the history of military science.

M.W.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

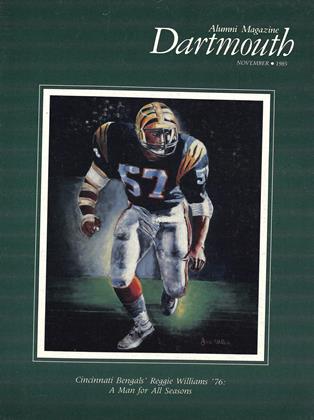

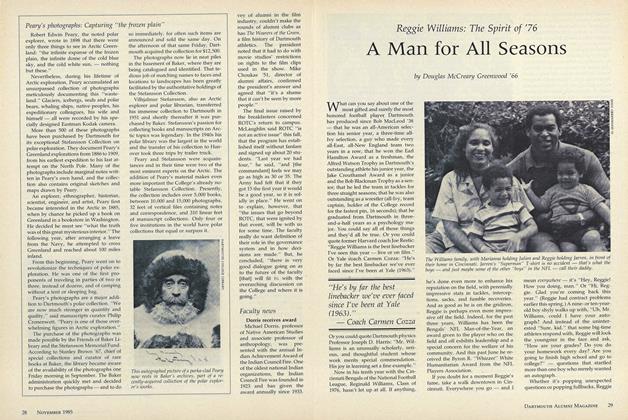

Cover StoryA Man for All Seasons

November 1985 By Douglas McCreary Greenwood '66 -

Feature

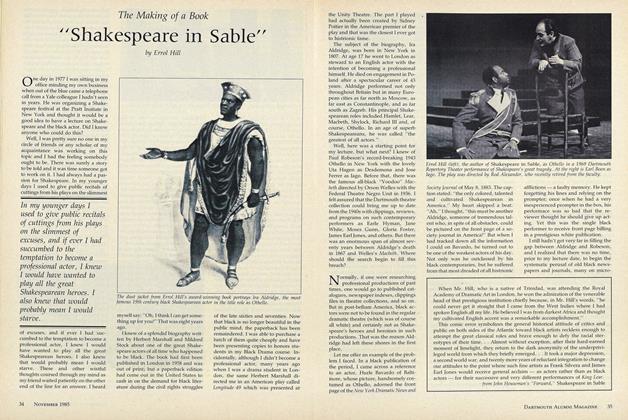

Feature"Shakespeare in Sable"

November 1985 By Errol Hill -

Feature

FeaturePolitics in an electronic age

November 1985 By Jim Newton '85 -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

November 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

November 1985 By Catherine A. Gates -

Sports

SportsTough days on the gridiron

November 1985

Mark Woodward '72

-

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

MAY 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksKHANS AND SHAHS: A DOCUMENTARY ANALYSIS OF THE BAKHTIYARI IN IRAN

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksWHAT DO UNIONS DO?

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

OCTOBER 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksAn Intriguing Account

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksTussling with Contradictions

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Mark Woodward '72

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

May 1934 -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF WRITING: FROM CAVE ART TO COMPUTER.

MARCH 1963 By ADELAIDE B. LOCKHART -

Books

BooksGENERAL EDUCATION IN THE SOCIAL STUDIES

February 1949 By Albert S. Anthony. -

Books

BooksBEHOLD OUR GREEN MANSIONS

January 1946 By F. S. Page '13 -

Books

BooksLIFE ALONG THE CONNECTICUT RIVER.

June 1939 By Harold G. Rugg '06. -

Books

BooksDEMOCRACY IN A CHANGING SOCIETY.

NOVEMBER 1965 By WALDO CHAMBERLIN