EXETER IN 1830. By William Gilman Perry 1842 M.D. EXETER IN 1776.

FEBRUARY 1973 JOHN H URD '21By Charles H.Bell Esq. 1844. With introduction and additional notes by Nancy C. Merrill. Hampton.N. H.: Peter E. Randall. 1972. Profusely illustrated. 164 pp. $15.

Out of print for many years, these two rare books, obtainable only with difficulty at top prices from specialized dealers, are now combined in a single handsome volume with a new introduction by Mrs. David Merrill, a new index, selected Exeter photographs, two additional maps showing Front Street and the center of town in 1776 and 1972, and a foldout on the back cover, a copy of the first printing in the New Hampshire Gazetteor Exeter Morning Chronicle of the Declaration of Independence.

Dartmouth senior Perry in 1842 could afford the best. He hired a barber to cut his hair for 11 cents and ate at the most expensive boarding house for $2.25 a week. With a sweet tooth he blew himself to licorice at 2 cents, horehound to candy ("for a cold") 5, two pounds of raisins 25, a quart of peanuts 8, pears and plums 6¼, and a peck of apples 12½. A horseback ride cost him 37½. but tuition was a major expense, S11.44.

As a retired Exeter doctor, he turned historian. "Imagine a house heated only by fireplaces, without furnaces or stoves; bedrooms with fires only when there was sickness; ice in summer only in a few houses; the well, the refrigerator, where were suspended buckets containing butter and other articles to be kept cool; in the outside, no railroads, telegraph, or telephone—and you have the conditions that awaited me in my introduction Exeter." (He was born in 1823).

With no modern soaps, families washed with "soft soap," made from fat and grease set aside in the house to fill a hogshead full of lye. In winter butter, dried apples, and carcasses of mutton selling for 2½ cents a pound arrived on pungs from back state to be swapped for salt, southern corn, and fish. Returning, pung drivers ate chunks cut from frozen masses of baked beans. Farm work and teaming were done principally by oxen.

Exeter in 1776 was even more primitive, but tremendously vital. Governor Bell describes the river affording passage to vessels of considerable size, shipyards building ships as big as 500 tons, cargoes being unloaded, carpenters and caulkers hammering and plugging, and long lines of teams dragging huge pines to the river banks. Unpainted, poor, and small houses gave little modern comfort to the population of only 1750. Women worshippers were isolated from men in the meeting house. The hardware store dealt briskly in gun flints, hour glasses, H and HL hinges, thumb latches, warming pans, and shoe and knee buckles. The drygoods store catered to eager women seeking Tammys and Durants, Dungereens, Tandems, Romalls, and Snail Trimmings, while the men at the iron-mongers sought Firmers, Jobents, Splenter Locks, and Cuttoes.

Every trader dealt in "spirituous liquor." "Good men, engaged in a religious duty, sometimes partook of the enticing cup with freedom." Christenings and funerals "must be observed by a plentiful oblation." Repairing to a tavern, selectmen found "means to moisten their clay; and the landlord scored the mugs and bowls of fragrant beverages to the account of the town." On circuit, "the judges ... were unable to hold the courts without spirituous refreshments."

Such was life in 1770'5. Relying on historical documents. Governor Bell points out to us the houses of the famous and the less famous and introduces us to military leaders and politicians who gave New Hampshire its political foundations some 197 years ago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

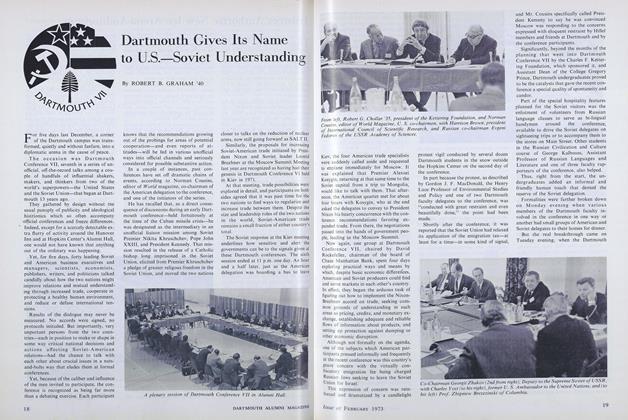

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1973 -

Feature

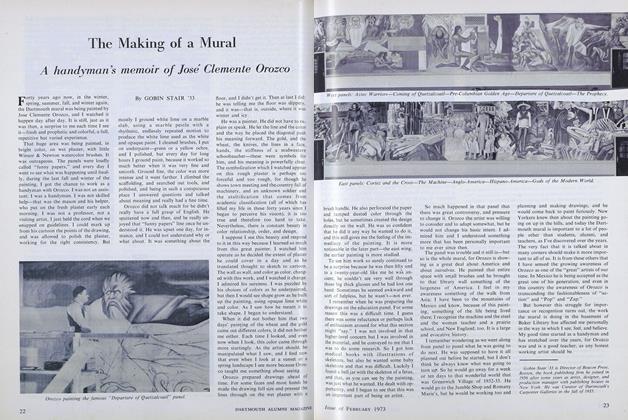

FeatureThe Making of a Mural

February 1973 By GOBIN STAIR '33 -

Feature

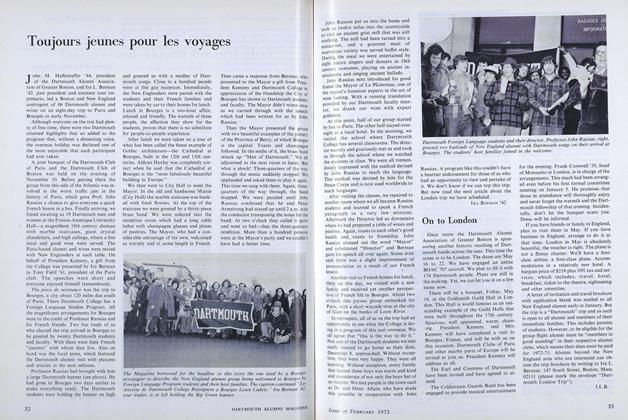

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

February 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

February 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

Books

-

Books

BooksLEPROSY in EUROPE

June 1929 -

Books

BooksREFLECTIONS ON THE HUMAN VENTURE.

July 1960 By ALBERT H. HASTORF -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

February 1920 By F.P.E., C.E.B. -

Books

BooksWARSHIPS OF THE WORLD

October 1944 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTHE STRUCTURE OF THE DEFENSE MARKET

MARCH 1968 By MARTIN L. LINDAHL '40h -

Books

BooksDEEP LAY THE DEAD

February 1943 By Oliver Linton Lilley '30.