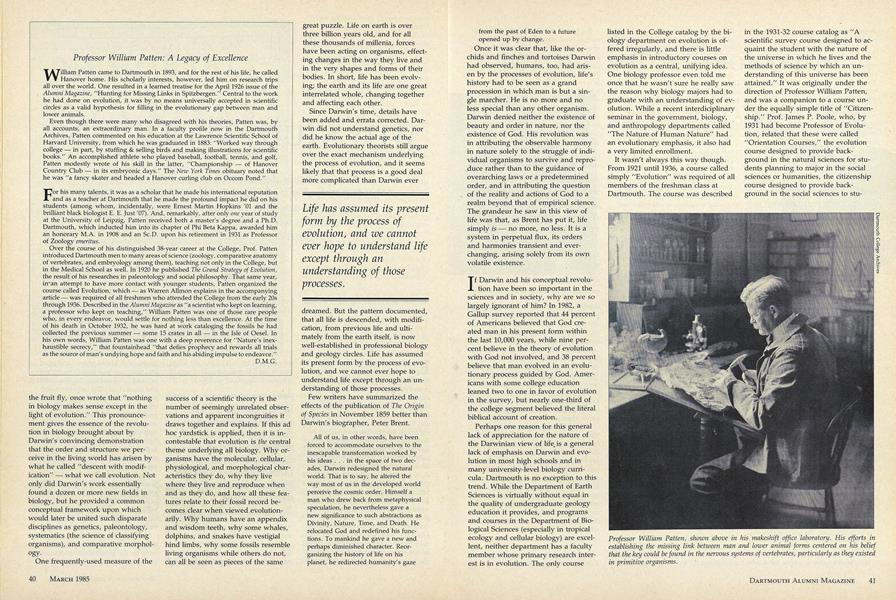

William Patten came to Dartmouth in 1893, and for the rest of his life, he called Hanover home. His scholarly interests, however, led him on research trips all over the world. One resulted in a learned treatise for the April 1926 issue of the Alumni Magazine, "Hunting for Missing Links in Spitzbergen." Central to the work he had done on evolution, it was by no means universally accepted in scientific circles as a valid hypothesis for filling in the evolutionary gap between man and lower animals.

Even though there were many who disagreed with his theories, Patten was, by all accounts, an extraordinary man. In a faculty profile now in the Dartmouth Archives, Patten commented on his education at the Lawrence Scientific School of Harvard University, from which he was graduated in 1883: "Worked way through college in part, by stuffing & selling birds and making illustrations for scientific books." An accomplished athlete who played baseball, football, tennis, and golf, Patten modestly wrote of his skill in the latter, "Championship-of Hanover Country Club in its embryonic days." The New York Times obituary noted that he was "a fancy skater and headed a Hanover curling club on Occom Pond."

For his many talents, it was as a scholar that he made his international reputation and as a teacher at Dartmouth that he made the profound impact he did on his students (among whom, incidentally, were Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 and the brilliant black biologist E. E. Just '07). And, remarkably, after only one year of study at the University of Leipzig, Patten received both a master's degree and a Ph.D. Dartmouth, which inducted him into its chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, awarded him an honorary M.A. in 1908 and an Sc.D. upon his retirement in 1931 as Professor of Zoology emeritus.

Over the course of his distinguished 38-year career at the College, Prof. Patten introduced Dartmouth men to many areas of science (zoology, comparative anatomy of vertebrates, and embryology among them), teaching not only in the College, but in the Medical School as well. In 1920 he published The Grand Strategy of Evolution, the result of his researches in paleontology and social philosophy. That same year, in an attempt to have more contact with younger students, Patten organized the course called Evolution, which as Warren Allmon explains in the accompanying article was required of all freshmen who attended the College from the early 20s through 1936. Described in the Alumni Magazine as "a scientist who kept on learning, a professor who kept on teaching," William Patten was one of those rare people who, in every endeavor, would settle for nothing less than excellence. At the time of his death in October 1932, he was hard at work cataloging the fossils he had collected the previous summer some 15 crates in all in the Isle of Oesel. In his own words, William Patten was one with a deep reverence for "Nature's inexhaustible secrecy," that fountainhead "that defies prophecy and rewards all trials as the source of man's undying hope and faith and his abiding impulse to endeavor."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

March 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY EVOLUTION?

March 1985 By Warren D. Allmon '82 -

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

March 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85

D.M.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW CUT SYSTEM

August, 1914 -

Article

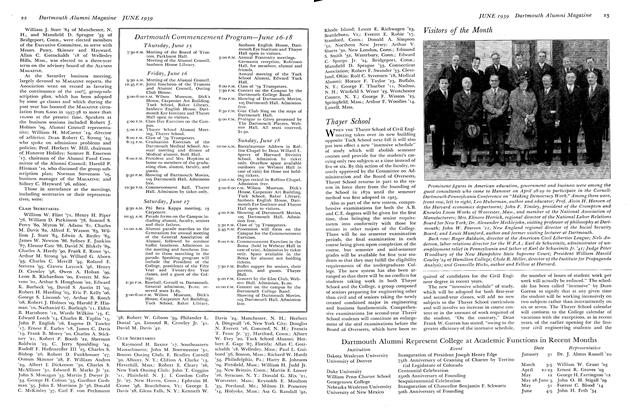

ArticleDartmouth Alumni Represent College at Academic Functions in Recent Months

June 1939 -

Article

ArticleFOR OLD BOOKS NEW DUST JACKETS

MARCH 1990 -

Article

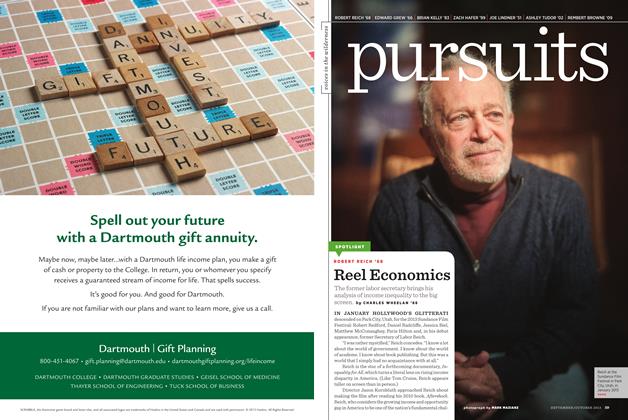

ArticleReel Economics

September | October 2013 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

NOVEMBER 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleFRENCH CULTURAL READER.

MARCH 1972 By JACQUELINE B. SICES