About 5,000 letters from Joseph Conrad have survived. They have escaped wars, shipwrecks, revolutions, silverfish, and the hands of embarrassed or indifferent owners. Some remain in private collections: the 300 to John Galsworthy, for instance, or the single letter that I saw last summer in a house at the very end of a high-hedged Devonshire lane, perhaps the only letter that still belongs to its original recipient. Most of the existing correspondence, however, is kept in libraries now: the New York Public, the Rosenbach in Philadelphia, the Beinecke at Yale and our own Baker.

Conrad hated the telephone, an impudent apparatus with no sense of timing. Consequently, some of his letters concern trivial matters: "There's a good train at nine thirty"; "Could you, by any chance, lend me five pounds?" Even these matters have their interest if only the five pounds separate Conrad from destitution, or the man on the train is Henry James. Yet most of the letters say far more; they are crowded with plans, opinions, judgments, noisy with groans of unhappiness and whoops of delight. They are, what is more, an extraordinary record of struggle and achievement in a symposium of tongues: Polish, French, and English, with asides in German, Italian, Spanish, Arabic, and Malay. As with his terrible Kurtz, all Europe went into Conrad's making and a good bit of Asia and Africa, too.

Formerly, anyone who wanted to look at this correspondence needed an unusually good library and a talent for bibliography. Many of the published letters are scattered through out-of-the-way journals and hard-to-find books, and they are often badly transcribed or tacitly doctored. About a third of them (ineluding some of the best) have never been published at all.

The Cambridge edition brings everything together, letter by letter, year by year. The first volume, published in 1983, covers Conrad's years at sea and his beginnings as a novelist. Volume Two, which should come out next year, shows Conrad by turns elated and despondent as he grapples with Lord Jim and "Heart of Darkness." Six more volumes lie ahead. Thanks to some welcome paving by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the journey toward their completion will be swifter.

Facing this often exhilarating but sometime giddy prospect with me is Frederick Karl, of New York University. I do my half of the editing in Hanover, an appropriate as well as a congenial place for the task. Conrad had Cunninghame Graham for a close friend, and Dartmouth has a fine selection of papers by and about him. Among other friends well represented in the Special Collections at Dartmouth are Edward Garnett, W. H. Hudson, and Stephen Crane. From Conrad himself we have some of his most remarkable letters: his correspondence with Cunninghame Graham about socialism, human nature, current books, Latin America, the destiny of the universe, and the proper way to rig a broken funnel in a storm.

For this rich slice of modern literary history, we can thank the generosity of alumni and the farsightedness of a professor, the remarkable Herbert Faulkner West '22. Herb West had the face (some people would add the temperament) of a prize-fighter and the soul of a man mad about books. By exhortation, cajolery, and sheer enthusiasm, he made the College acquire a beautifully coherent collection of twentieth-century books and manuscripts. That collection is a joy to use.

Editing letters is a diplomatic business. Heirs and collectors have to give their blessing. Owners must be persuaded that letting a scholar handle their manuscripts is not like letting the Vandals loose on Rome. After copying, the texts have to be printed in a form that satisfies the fearsome standards of modern bibliographers without driving the ordinary reader (if that is the right term for critics, students, or members of the literary public) wild with irritation at cryptic editorial symbols. What, for example, to do about Conrad's distinctly personal spelling and punctuation? Should we clean them up and make the compositor and the ordinary reader happy? Or should we leave the literary dust, if dust it be, exactly where it is? In this case, the answer is determined by the special nature of Conrad's letters. Those in English or in French were writ ten in foreign languages; rubbing out the traces of his heroic struggles to master them would be scandalous. Nevertheless, one does not want to patronize him with a string of glaring sics. Fidelity requires a certain tact.

The task that concerns me most is to make a solid but unobtrusive framework for the letters. Here again, compromise and balance are vital. Each volume needs an introduction and notes that put the correspondence into perspective without blocking the view. Sometimes the letters throw light upon the novels. Sometimes the novels throw light upon the letters, but the light can be hidden under a bushel or two of allusions that were clear to Conrad's friends but not, immediately, to us. Sooner or later, most readers need a little help.

Take, for example, the underlying patterns in the second half of 1899. Conrad was collaborating with Ford Madox Ford on The Inheritors, a satirical novel peopled by scantily-disguised versions of Balfour, Joseph Chamberlain, Flenry James, and Leopold, King of the Belgians. The year before, Conrad had seen his bones exposed in an X-ray machine, and he was on very good terms with H. G. Wells; in the not exactly serious plot of The Inheritors, the world has been invaded by a pitiless race of Fourth Dimensionists. Meanwhile, in the actual world, Britain and the Boer republics had gone to war. In his correspondence, Conrad had to deal with his Polish cousins, who thought that the Boers were a freedom-loving people oppressed by brutal imperialists, his friend Ted Sand erson, who took his support of British policies in South Africa to the point of going off to fight there, and his friend Cunninghame Graham, who regarded the whole affair as a falling-out between two burglars. The war raised all sorts of questions, not least in the mind of a Polish-born but naturalized Briton, about nationality, cultural identity, loyalty, and the fate of native peoples. In the summer of 1899, Conrad made friends with Hugh Clifford, the Governor-designate of North Borneo, who had challenged him on his knowledge of Malay customs. This was the year in whic Lord Jim, a work obsessed with the problem of "us and them," began its unexpected growth from a "sketch" to a fullscale novel. So many dots want joining up.

And that was only part of the agenda for the second half of the year. The world kept pressing. Conrad was, as usual, desperately short of money. The son of his oldest 'English friend was found naked, dead, and probably murdered on the dismal Essex marshes. His own son was learning to talk. The correspondence is full of references to these events and many more.

The notes and introduction should clarify the references and bring out the patterns. That means, for instance, ferreting out the coroner's report on the murder, or picking out a lurid battlepiece from the popular press to show why Conrad so detested war correspondents. It means asking how much he knew about pirates in Borneo or current theories of physics. It means above all, making the connections among those anticipations of Lord Jim, or between the X-ray machine and the Fourth Dimensionists.

To what end is all this detection and all this joining up of dots? There are as many answers as there are ways of thinking about literature or history. That is why too much annotation is as bad as too little. In the long run, it is the reader who chooses what kind of significance the letters have. As editors, we simply assume that travellers through the labyrinth have more than one destination.

The most obvious interest or value the letters can offer is biographical. They can tell us what Conrad thought or felt in September 1894 or March 1909. More precisely, they can tell us what he said he thought or felt: rather an important difference, as almost anyone who has ever written a letter knows. With the same reservation, they can tell us about his plans and intentions his longing to go back to sea, or his first speculations about The Secret Agent. They can tell us whom he met and when, where he went and why.

Once again, however, the further significance may be concealed. What Conrad doesn't say about his life may be as important as what he does. Even if we had every letter he ever wrote (we surely do not), we would have to listen for the silences. It's an all too common mistake of biographers to assume that evidence obeys the principle of survival of the fittest. They might learn from Dr. Watson, a simple biographer but willing to learn. Sherlock Holmes once solved a case not because a dog barked but because it didn't.

On one subject, Conrad is always explicit. Anyone interested not so much in the author as in the author's environment interested, that is, in the sociology of editing, publishing, and reading will find in his negotiations, intrigues, and frustrations a vivid record of a modern author's struggle to be serious and survive.

Again, taking Conrad as a representative figure (even a genius lives at a time and in a place), we can see in his letters a refraction of contemporary ideas, of contemporary consciousness. Late in the nineteenth century, the implications of entropy and Darwinism beg an to register on the public mind. When, in one of the Dartmouth letters, Conrad wrote to Graham about the fut ure of the universe, he expressed a common idea in uncommon terms: The fate of a humanity condemned ultimately to perish from cold is not worth troubling about. If you take it to heart it becomes an unendurable tragedy. If you believe in improvement you must weep, for the attained perfection must end in cold, darkness and silence.

To turn from cosmic to local time when he joked about bomb-throwing anarchists, he lived in a period when the ideal of "propaganda by deed" had just become a messy reality.

Personally, what I most enjoy and what fascinates me are the letters themselves, regardless of their value as a mirror of the world outside. I detect in them not one but many Conrads. Each correspondent evokes a different attitude. To T. Fisher Unwin, his first publisher, he wrote about fiction: Everything is possible but the note of truth is not in the possibility of things but in their inevitableness. Inevitableness is the only certitude; it is the very essence of life as it is of dreams . . . Our captivity within the incomprehensible logic of accident is the only fact of the universe.

To Ted Sanderson, schoolmaster and soldier, he wrote about Sanderson's fiancee: Only the other day I've re-read Miss Helen's letter the letter to me ... It is so unaffectedly, so irresistibly charming and profound too. One seems almost to touch the ideal conception of what's best in life. And personally those eight pages of Her writing are to me like a high assurance of being accepted, admitted within, the people and the land of my choice.

And to Marguerite Poradowska, his aunt by marriage, he wrote, originally in French, about her latest novel: I want my book!!!!!!!!!! No! Your book. I am waiting for it, I must have it at once if not sooner! I do not understand your hesitation. It is probably to torment me. You have succeeded (here a nervous fit) Ah, I am better. A little glass of cognac has restored me.

To represent the fertility and complexity of fiction, the critic Mikhail Bakhtin used the musical concept of polyphony. The concept fits Conrad's letters well: rather than a single, simple line, you can hear in them a choir of interweaving voices.

Then are Conrad's letters fictions? To be sure, whether to impress, persuade, or win sympathy, they were made up, and made up by a man who played to his correspondents like a story-teller who knows what people want to hear. One might even say that he was telling stories to himself. In our banal way, most of us ordinary letter-writers sometimes do the same. Nevertheless, although the idea of fiction does apply, I prefer not to think of the letters as five thousand fragmentary Lord Jims. Putting aside the simple communications of the "Thank you for dinner" variety, the letters (some of them, incidentally, considerably longer than this article) can best be described as essays.

They are essays in the sense Montaigne originally gave the word: trials, explorations, a writer's attempts to understand is medium and his circumstances. Sometimes Conrad's letters are meditations, sometimes bursts of passion; sometimes they expose and sometimes they conceal, but always they open up the possibilities of language.

They gave Conrad the chance to think, as it were, aloud; even the extraordinary descriptions of solitude and desolation were written for his friends as much as for himself. They stand, in other words, at the place where public and private meet. Talking about "the real Conrad" begs more questions than I care to contemplate, but there is certainly a Conrad, there are Conrads in the correspondence that cannot be found elsewhere. He always had trouble with the mechanics of fiction. In the correspondence, without the hindrances of characters and plot, he could more easily achieve a match of words to feelings and ideas. As he wrote to Edward Garnett, his "dear encourager": I will not hold my tongue! What is life worth if one cannot jabber to one's heart's content? W

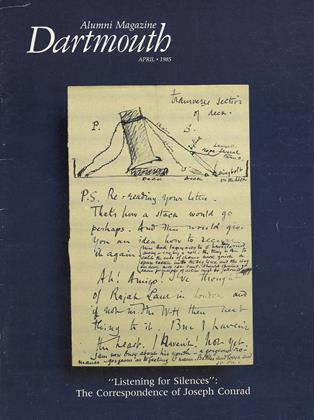

This is the opening page of the letter on the cover from Joseph Conrad toR. B. CunninghameGraham, with, among other things, Conrad's remarks on how a steamer's smokestack couldbe replaced.

The Badge alluded to here by Conrad, is, of course, Stephen Crane's remarkable novel, The Red Badge of Courage, which appeared tivo years before Conrad composed this letter.

Prof. Laurence Davies, a native of Llanivrtyd, Wales, took his M.A. at Oxford andhis Ph.D. at Sussex. He is a Faculty Masterin the Choates and teaches English, comparative literature and environmental studies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMinimum Standards

April 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

FeatureKey to Success: Dartmouth's Athletic Sponsor Program

April 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureHistorical Notes on the Upper Valley

April 1985 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureFROM THE DESK OF THE PRESIDENT

April 1985 -

Article

ArticleWorth his salt

April 1985 By JOseph Berman '86 -

Article

ArticleBud Brown '25: Happy trails keep him smiling

April 1985

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureFather Prior

OCTOBER 1966 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGreat Expectations

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84