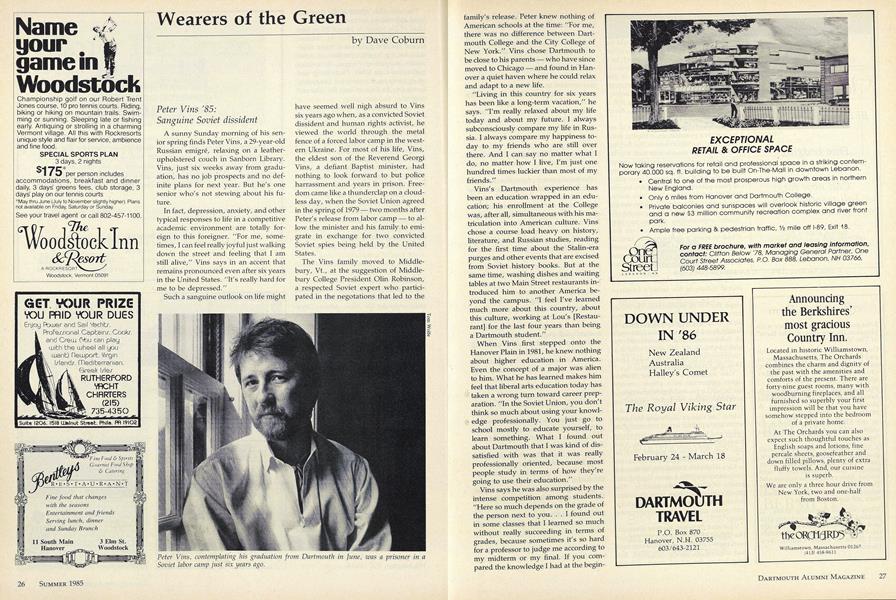

A sunny Sunday morning of his senior spring finds Peter Vins, a 29-year-old Russian emigre, relaxing on a leatherupholstered couch in Sanborn Library. Vins, just six weeks away from graduation, has no job prospects and no definite plans for riext year. But he's one senior who's not stewing about his future.

In fact, depression, anxiety, and other typical responses to life in a competitive academic environment are totally foreign to this foreigner. "For me, sometimes, I can feel really joyful just walking down the street and feeling that I am still alive," Vins says in an accent that remains pronounced even after six years in the United States. "It's really hard for me to be depressed."

Such a sanguine outlook on life might have seemed well nigh absurd to Vins six years ago when, as a convicted Soviet dissident and human rights activist, he viewed the world through the metal fence of a forced labor camp in the western Ukraine. For most of his life, Vins, the eldest son of the Reverend Georgi Vins, a defiant Baptist minister, had nothing to look forward to but police harrassment and years in prison. Freedom came like a thunderclap on a cloudless day, when the Soviet Union agreed in the spring of 1979 - two months after Peter's release from labor camp - to allow the minister and his family to emigrate in exchange for two convicted Soviet spies being held by the United States.

The Vins family moved to Middlebury, Vt., at the suggestion of Middlebury College President Olin Robinson, a respected Soviet expert who participated in the negotations that led to the family's release. Peter knew nothing of American schools at the time: "For me, there was no difference between Dartmouth College and the City College of New York." Vins chose Dartmouth to be close to his parents - who have since moved to Chicago - and found in Hanover a quiet haven where he could relax and adapt to a new life.

"Living in this country for six years has been like a long-term vacation" he says. "I'm really relaxed about my life today and about my future. I always subconsciously compare my life in Russia. I always compare my happiness today to my friends who are still over there. And I can say no matter what I do, no matter how I live, I'm just one hundred times luckier than most of my friends."

Vins's Dartmouth experience has been an education wrapped in an education; his enrollment at the College was, after all, simultaneous with his matriculation into American culture. Vins chose a course load heavy on history, literature, and Russian studies, reading for the first time about the Stalin-era purges and other events that are excised from Soviet history books. But at the same time, washing dishes and waiting tables at two Main Street restaurants introduced him to another America beyond the campus. "I feel I've learned much more about this country, about this culture, working at Lou's [Restaurant] for the last four years than being a Dartmouth student."

When Vins first stepped onto the Hanover Plain in 1981, he knew nothing about higher education in America. Even the concept of a major was alien to him. What he has learned makes him feel that liberal arts education today has taken a wrong turn toward career preparation. "In the Soviet Union, you don't think so much about using your knowledge professionally. You just go to school mostly to educate yourself, to learn something. What I found out about Dartmouth that I was kind of dissatisfied with was that it was really professionally oriented, because most people study in terms of how they're going to use their education.

Vins says he was also surprised by the intense competition among students. "Here so much depends on the grade of the person next to you. . . I found out in some classes that I learned so much without really succeeding in terms of grades, because sometimes it's so hard for a professor to judge me according to my midterm or my final. If you compared the knowledge I had at the bginning of the course - for example, a course on American economics - and tried to value how much I had learned at the end of the course, it would be tremendous. But he's not trying to judge me in terms of how much I learned, he's trying to judge me in terms of how my knowledge compared to others in the class. He'll say, 'You didn't put enough time, enough effort into the course,' without realizing that for me it's just a completely different mentality about economics."

Vins was born into a tradition of rebellion. His grandfather, a Baptist minister, died in a labor camp while serving time for illegal church activities. His father spent eight years in labor camps and several more underground, hiding from the KGB as he moved from place to place preaching the forbidden lessons of Christianity. When Peter was seven, his parents told him he must decide whether to join the Communist Party's youth organization. It was an easy choice: "When my parents told me that I had to make a decision, they kind of implied that if I decided to join the party ... I would be one of the people who participated in putting my grandfather in jail, in killing him."

As a young boy, Vins thought he would follow in his father's footsteps and take up the ministry. He romanticized the life of persecution. At 14, he turned away from the church, but not away from the political ideals that his family stood for. Later he read the work of Solzhenitsyn and romanticized the idea of prison life. He recalls now that "unconsciously, I knew that when I was 18 or 19, I was going to prison."

Vins became active in the human rights movement after police arrested his father for his underground religious activities, which included organizing printing presses to print Bibles. "By accident," as Vins put it, Andrei Sakharov wrote some protest letters defending his father and helped get information about his father's trial to the world press. Vins saw then the value of protest, and he began to work with a group of dissidents in Kiev who were attempting to monitor compliance with the human rights guarantees of the Helsinki accords. The group's main activities were to collect information on human rights violations and write protest letters condemning them.

Vins was 23 when he was arrested. The formal charge was that he was not working - a situation the government had assured by having him fired. But long before the actual arrest, officials had tried to persuade Vins to give up his role with the human rights group. "Before they arrested me," he said, "they tried to talk to me at least four times, like maybe every four or five months. I would just walk on the street and they would come to me, a few people. They would just push me in a car, they would take me to one of their headquarters - KGB headquarters. I was 18 or 19, and they would have five or six or seven men in their fifties and sixties who would just sit in front of me and talk for four or five hours, trying to convince me that I am wrong in trying to fight the government, that I have no idea, no political philosophy, no reason, that I'm just trying to pay back to the government what it did to my family."

For his supposed crime, Vins was sentenced to a year in a forced labor camp in the western Ukraine. His memories of the camp are rendered in shades of gray. At first he worked with a sledgehammer, pulverizing rocks into gravel, but later he was moved to a less demanding job in a factory. Camp life at its worst meant living in solitary confinement and enduring beatings by the guards and at its best meant living in a huge barracks occupied by 150 to 200 prisoners. Vins found his happiness in meager portions: "an extra piece of bread or not working on Sunday."

In the barracks, he said, "Everybody smokes, of course. Everybody takes a shower once a month. The highest law is mind your own business. You don't help anybody next to you. You go inside the barrack, you can't concentrate because it's constant noise. You have 150 people in a big room. Some people smoke, some people scream, you can't even write a letter or read a book because it's so disturbing."

Vins was released in February 1979, a few months before his father was to complete a five-year prison term and begin five years of internal exile in Siberia. But after his release, Vins learned that the Soviet Union had agreed to exchange the family for two Soviet spies being held by the U.S. government.

Vins's father was well known in Baptist circles in the West as a symbol of religious persecution in the Soviet Union - so well known, in fact, that upon the family's arrival in this country, the Reverend Vins was invited to Washington to attend a church service with another prominent Baptist, Jimmy Carter.

"For us, it was not just a matter of luck. The shock was so big to us, being allowed to go the West, it was like the skies opening up and you see somebody coming from the sky - E.T. or God or somebody - telling you you're free and you can do whatever you want. At that point, life was so grim and so gray, we had no choice. I knew I was going to prison again in the future. I didn't know when, I didn't know if it was going to happen in a few weeks, a few months, a few years. I didn't know if it was going to be for five years or ten years or 12 years. And everyone didn't think about leaving Russia because it was almost impossible. Only a few people apply because it's really hard to leave the country."

Life on the Hanover Plain has not been without its difficulties. Vins spoke little English when he arrived in the U.S., and language proved a barrier not only in the classroom but in the job market. Vins scoured Hanover looking for work. Finally, Bob Watson '59 took him on as a dishwasher at Lou's Restaurant and soon moved Vins up to waiter and then to night manager. "Part of it was my potential, my performance, but part of it was that Bob Watson really believes in the American Dream," says Vins.

So far, Vins's experience in America has been limited almost exclusively to pastoral New England college towns. And his only work experience comes from his jobs at Lou's and Bentley's, another downtown eatery. Vins is contemplating a career in the restaurant business, perhaps in Boston. But he says that maybe he is aiming in that direction "just because I don't know my capacity in this country. I have done so little practical in my life," he says. "I know so little about real life."

Vins, given the choice, would rather not talk about his life in the Soviet Union. He is happy to forget. "I have changed to the point where my life in the Soviet Union doesn't exist as a reality for me anymore. I'm glad I have forgotten, because my first year in this country, my second year, I used to have constant nightmares. If I had the same dreams in the Soviet Union, it wouldn t be nightmares, it would be just part of my everyday life.

"Living in the Soviet Union, you don't realize - only coming here, being in this country for a few years and looking back, sometimes it shocks you. Sometimes it seems so far away and faded, like something that didn't happen to me, that sometimes I say, 'Well, maybe I read it in a book."

Peter Vins, contemplating his graduation from Dartmouth in June, was a prisoner in aSoviet labor camp just six years ago.

Dave Coburn is a staff writer for The Valley News.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Humanist Ponders the Future of Liberal Education

June 1985 By Charles T. Wood -

Feature

FeatureAn Apple on Every Desk

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Train Robbery

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wentworth Bowl

June 1985 By Barbara J. MacAdam, Curator, Hood Museum of Art -

Cover Story

Cover StoryValedictory Address

June 1985 -

Feature

FeatureReunions 1985

June 1985 By Robert Frost

Article

-

Article

ArticleHistoric Home Purchased

December 1934 -

Article

ArticleThayer School Partner

DECEMBER 1968 -

Article

ArticleCollis Miniversity: "Catering to Personal interests"

MAY 1985 -

Article

ArticleDesert Island Poetry

Sept/Oct 2000 -

Article

ArticleDavid R. Gavitt '59: Steering the Big East to the big time

MAY 1985 By Peter Mandel -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

October 1932 By S. C. H.