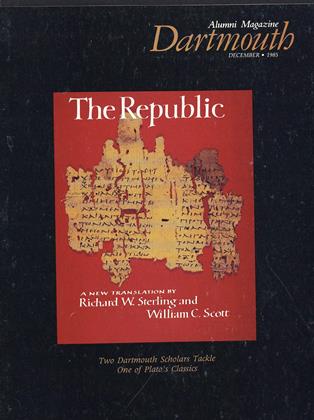

"Astronomy compels the soul to look upwards and leads us from this world to another," wrote Plato in 529 B.C. in The Republic.

Looking upwards at the heavens is very much in vogue these days, with Halley's Comet a hot media topic and a spur to sales of home telescopes. But Dartmouth astronomer Gary Wegner's interest in the night sky is somewhat less faddish. The 40-yearold associate professor of physics and astronomy has spent many years studying the physics of stars and has achieved international recognition for his research on elliptical galaxies.

When Wegner came to Dartmouth three years ago, he inherited a tradition of astronomical research that is even more enduring, going back to the very beginnings of the College. Dartmouth scientists have distinguished themselves in the study of the heavens ever since 1785, when the College took delivery of its first telescope - a relatively primitive instrument that was ac- tually ordered 13 years earlier by Eleazar Wheelock himself.

Some of that history was passed on to Wegner when he received tenure at Dartmouth and was given a gift from a colleague, a copy of Natural Philosophy atDartmouth. The slim volume on the history of the physical sciences at Dartmouth was in 1974 by Sanborn C. Brown '35, a renowned physicist at MIT, and longtime Dartmouth physicist Leonard M. Rieser '44. On the title page, Rieser had penned, "Now that you have tenure, you should know how it all began."

One senses, though, that however much Wegner appreciates Dartmouth's historical contributions to his field, he doesn't feel he missed much by arriving in Hanover 200 years after the school's first telescope. Like most disciplines - or perhaps even more than most - research in astronomy today bears, little resemblance to the primitive study of "natural philosophy" of yesteryear. In an age when it is possible to fetch rocks from the moon and send satellites slicing through the tail of a comet, astronomy is an exciting field to be in.

"I would say this will be looked back on as the golden age of astronomy," Wegner says, pointing to ever-improving technologies like the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) that allows scientists to probe deep into space, and the sophisticated computer systems that do the infinite calculations astronomers once did by hand.

The flip side, of course, is that the discoveries to be made by astronomers today are pretty arcane. Long gone are the days when important discoveries could be made in virtually accidental fashion by sky-scanning amateurs. Sir William Herschel's discovery of Uranus in 1781 is perhaps the classic example of such a find. He first took the planet for a comet and dutifully reported it as such to the Royal Astronomical Society, only to finci out its true planetary character after a few weeks' observation.

Nowadays, says Wegner, professional astronomers would be helpless without their "monster telescopes" and huge computer systems. But even with the most advanced equipment, they remain frustrated in their attempts to answer some fundamental questions regarding the nature of the universe. For instance, says Wegner, "Nobody knows for sure, but it's a reasonable guess that planets are pretty common." Still, he notes, scientists have yet to discover conclusive evidence of a planet orbiting a star outside of our solar system.

In large part, it was one of the "monster telescopes" - offering the chance to do some significant research - that lured Wegner to Dartmouth. A compact, softspoken man, Wegner grew up in Seattle, went to the University of Arizona for his bachelor's degree, then returned to Seattle to earn his Ph.D. at the University of Wash- ington. From there, his research carried him far afield to the Australian National Uni- versity, to Oxford University, and to the South Africa Astronomical Observatory in Cape Town. Upon his return to the States, Wegner secured a position at the University of Delaware, where he taught until 1982 before coming to Dartmouth that fall.

Dartmouth's membership in a consortium with access to one of the world's most powerful telescopes made the College's offer an attractive one. The Shattuck Observatory, up by the Bema, was one of the bestequipped in the country when it was built in 1854 but is now almost as much an antique as the telescope that Eleazar ordered. About ten years ago, Wegner relates, the University of Michigan had a fine telescope but no money to move it to a better location. With collaboration from MIT, which provided "the computer gadgetry and programming," and Dartmouth, which contributed funding to the project, the telescope was installed on a mountain in Arizona. Now, Dartmouth gets several weeks of observation time every year on the huge telescope at the Kitt Peak Observatory.

"Those telescopes are essentially state-ofthe-art instruments on a really good site," Wegner says. "You could count telescopes of comparable quality on the fingers of your hand."

Wegner credits the College's participation in the Kitt Peak consortium with fueling a revival of interest in Dartmouth as a place to study the stars. Around the turn of the century, the College's astronomy program was on a par with those of other preeminent institutions. But then interest in astronomy research at Dartmouth waned and has only been rekindled in the past decade. Wegner says that more graduate students in astronomy are now applying to Dartmouth because, with the Kitt Peak connection, "we really have the opportunity to discover something fairly fundamental, something about the basic nature of the universe."

For most of his career, Wegner was concerned with the physics of stars themselves, particularly with the study of white dwarfs - "collapsed" stars that have a density many times greater than that of the sun. In the past four years, however, the focus of his research has been elliptical galaxies-vast symmetrical groupings of stars that differ markedly from other types of galaxies such as the Milky Way, in which our solar system is located.

Wegner calls elliptical galaxies "very simple" in comparison to our own, but he is quick to add that "basically, scientists don't know much about galaxies in general. We've got a lot of detail, but we don't know what it all means. You know, a galaxy like the Milky Way, for instance; we live right in it but you can't see the forest for the trees - it's got all kinds of spiral arms that are very complicated. Motions of elliptical galaxies are the simplest, but they're still extremely complex, and we don't even understand them."

The way astronomers try to understand things, explains Wegner, is "to observe hundreds of them and then look for correlations between different observable parameters." This was the idea behind a study project on elliptical galaxies that Wegner and a group of internationally-known scientists have been working on for several years. Wegner had previously done some research on the brightness of galaxies, and he was invited to join the project after his work was noticed by the other astronomers involved in the study. The members of the group have worked all over the world, traveling to observation sites in Chile, Arizona, and the United Kingdom to do research. The group has now stopped collecting new data and is compiling the information gathered so far. Last summer, Wegner and Dartmouth played host to the group, giving them a forum to share the information they had. "It's about time to write everything up and publish it," says Wegner. "I can't really say at this time we've got one single earthshattering result that will change the way man looks at the universe, but we've got some really good basic data." He notes that the group should be able to draw some conclusions about elliptical galaxies, particularly about their origins.

While Wegner's research interests are fairly esoteric, most of his classroom time is spent teaching elementary astronomy courses to undergraduates. The majority of ,his students are non-science majors, and the course is a survey of the subject that steers clear of mathematics entirely. It is a heavily-subscribed course, one that usually garners enough enrollment to put it among the six most popular on campus. "I think astronomy has a strong appeal to a lot of people for a number of reasons," Wegner says. "A lot of people have gone out at night and seen the stars and felt this awe of the heavens and want to know about it."

Does it matter to Wegner that his research on elliptical galaxies or white dwarfs holds little meaning for the average person? Wegner has obviously heard the question before, and his response is well-rehearsed: He believes both research and teaching in astronomy are important, even though the subject may never have any practical application to the lives of students.

"I think the pursuit of the truth which involves pure research is very important to society" was how Wegner explained it in a recent interview with The New HampshireTimes. "After all," he said, "if you go back to the Middle Ages, the whole populace lived in fear and ignorance. There were just a few educated people and the populace believed essentially what they told them. I think with modern society we have to get away from that." He went on to rue the fact that "ordinary science is much less spectacular [than a pseudo-science like astrology]." He called the Chariot of the Gods theory, about prehistoric visitations from outer space, for example, "complete garbage. The people don't know enough about science to reject it and a lot of people believe it." He explained the approach of the objective scientist as being part intuition ("to figure out what the answer is and then go look for it . . . one good example of that is Newton ... he had a tremendous physical intuition and a real feeling on how nature behaved") and part hard work ("in a sense it's a game and it has very definite rules and you've got to play by the rules . . . the rule is if the observations and the theory disagree . . . you have to reject the theory or modify it").

He feels the mission of the astronomer is "trying to find the truth about man's place in the universe. I think it's very important that we know what the nature of the universe is as clearly as possible."

Indulging in such philosophical ruminations is difficult while Wegner is actually working on the big telescope at Kitt Peak. The observers are in a small room packed with equipment, constantly taking measurements and pinpointing stars in the crosswires of the scope. "When you're observing, it's really hard work. You don't sit out there and gaze at the stars." But uncontrollable feelings of awe sneak in nevertheless, he says. "Yes, I do have mystical feelings, but it depends on what your definition of mystical is. I have a feeling of awe when I think of how old the universe is and how big it is. And there are so many mysteries we haven't solved [that] I'll never see answered in my lifetime."

The father of five, Wegner doesn't find much time for leisure pursuits between family, teaching, and flying off to peer through telescopes in Arizona or Chile. But if he does find some free time, he's likely to spend it working on the science fiction novel he's been writing for the past five years. Set in A.D. 14000, the book - now a 200-page manuscript - is "about the future of mankind after man's gone out and colonized the stars . . . about who's left after everyone's gone." Wegner sees science fiction writing as both an escape from the rigors of astronomy and as a means of indulging his boundless fascination with the universe. At the same time, he finds it an outlet for the otherwise suppressed political animal inside, a forum in which he can "criticize certain people and aspects of society that you couldn't do ordinarily."

Wegner has also written several papers on astronomy, but writing a textbook holds no interest for him. "The thing about writing a book in astronomy these days is that probably within one or two years of being published it's obsolete. Things change so quickly. I'd like to write something that kind of lasts."

But Wegner knows that even with the most sophisticated equipment at his disposal, making the big discovery that will ensure immortality is as much a matter of luck as anything else. He says he's content to get satisfaction and enjoyment out of what he does every day and to add what he can to astronomical understanding.

"I would like to be remembered as someone who got the answer right more often than wrong," he said in The New HampshireTimes. "Unless you're an extremely exceptional person - a Newton or an Einstein - in a hundred years nobody's going to remember you. So, I'd like to think that I will contribute something to human knowledge . . . The most important thing is to try to contribute to the sum of what people know about."

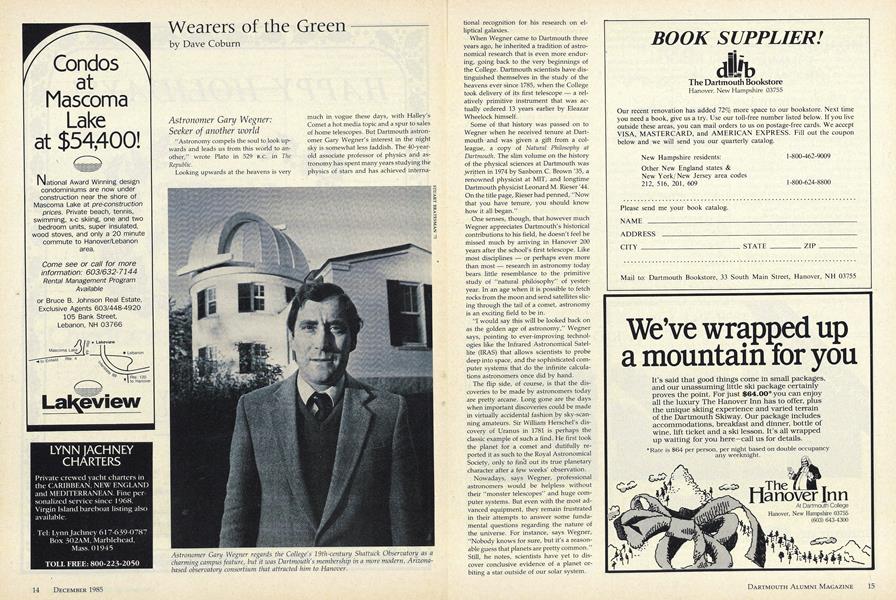

Astronomer Gary Wegner regards the College's 19th-century Shattuck Observatory as acharming campus feature, but it was Dartmouth's membership in a more modern, Arizonabased observatory consortium that attracted him to Hanover.

Dave Coburn, who wrote the profile of Sovietemigre Peter Vins in the Summer issue, is aneditor for The Valley News.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn the Air

December 1985 By Michael Berg '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

December 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTranslating Plato's Republic

December 1985 By Kathie Min -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

December 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

December 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Sports

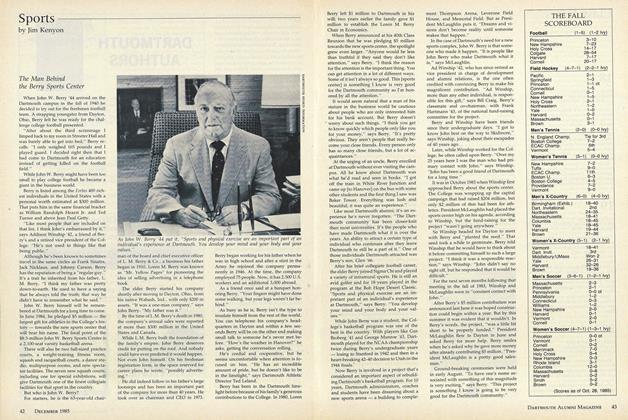

SportsThe Man Behind the Berry Sports Center

December 1985 By Jim Kenyon