Somewhere between adolescence and middle age, most of us begin to wonder how far back we can trace our roots and what we'll find if we do. Henry Meiggs "Monk" Keith '23 is no exception. He knew he had an illustrious family when he came to Dartmouth in 1919 on the advice of his uncle, Minor C. Keith, president of the United Fruit Company. He also had heard the claims that his mother's family had remained Purely Spanish for 400 years in Central America until his father, John Meiggs Keith, married his mother, Rosa Alvarado. But it was not until after he had graduated from Dartmouth in 1923 and had gotten a few years of experience and employment behind him, first with Pan American Airways when it was mapping out its original routes through Central America and then as a bank note representative for the American Bank Note Company, that he sought confirmation of the family stories.

Then he discovered that his mother's family had been traced back over 21 generations in Central America and another 80 years in Spain. Fascinated, yet wanting more than just lists of names, Monk began to look for more information. He found histories and legends describing several of his more colorful ancestors. Pedro de Alvarado, for example, came with Cortes to Mexico in 1490 and marched through Central America, conquering Guatemala, Salvador, and Honduras, and founding the city of Quito, Ecuador. Alvarado returned to Mexico and built an armada of 400 vessels to go to the Spice Islands but died when a horse fell on him before he began the journey.

Monk collected all the histories and legends that he found, combined them with the genealogical data, and published the book Historia de la Familia Alvarado-Barroeta. It includes many items of general interest: Indian legends, explanations of some place names in Mexico, and bits of Central American history during the early Spanish years. For example, to this day there is a pueblo named Quetzaltenango, "the place of the quetzal." The name was given the town by Pedro Alvarado in the 1400s, after he defeated a particular Indian leader. Toward the end of the battle, legend says that the Indian leader turned himself into a quetzal, a colorful bird, in a desperate attempt to kill Alvarado. After Alvarado slew the bird, he was so struck by the beauty of its feathers that he named the nearby pueblo in its honor.

Throughout his life, Monk Keith was often reminded of his paternal heritage, too. Originally, he had come to Dartmouth to improve his English. "I was very conscious of my deficiency so I took many English courses," he recalled in a recent letter to classmate Charles J. Zimmerman, "and the prof asked me if I was Scotch because of the way I pronounced the 'r'!" Although the professor was referring to Monk's Spanish pronunciation, he was close to the mark. Monk's father's ancestors, the MeiggsKeiths, were illustrious, hardworking, and adventuresome Scotsmen. Their tale begins on this continent in New York with Henry Meiggs, who sailed to San Francisco in 1849, shipping a load of lumber which he sold for 20 times its original cost. He made a fortune in California, and in 1854 he went to Chile to build railroads where no one else had been able to before. Soon he moved on to Peru. While there, he was asked to come to Costa Rica and build railroads. He turned that job over to an in-law, Minor H. Keith, who built the rail line from one coast of Costa Rica to the other. The banana trees he planted along the railroad became the foundation of the United Fruit Company which his son, Monk Keith's great-uncle Minor C. Keith, founded.

In 1929, a few years after his graduation from Dartmouth, Keith's great-uncle died and left a large amount of stock in the United Fruit Company to him. But the stock was devalued before the estate was settled during the Depression, and "in the end I got nothing except a bronze bust, which I still have," Keith said. But, in fact, Keith's predecessors left him a great deal more: a colorful past, a sense of adventure, and a clear, well-documented place in history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

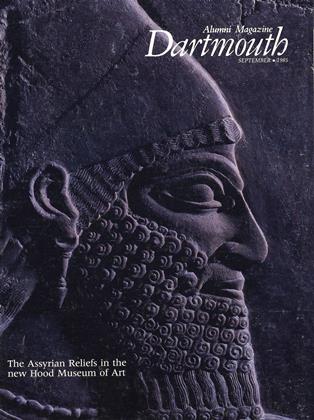

FeatureFrom "a few curious Elephants Bones" to Picasso

September 1985 By Jacquelynn Baas -

Feature

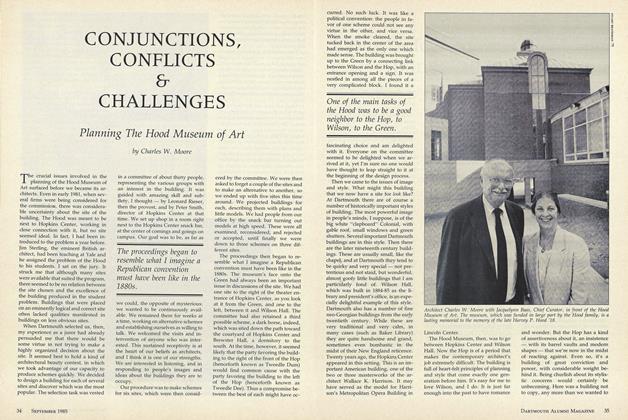

FeatureCONJUNCTIONS, CONFLICTS & CHALLENGES

September 1985 By Charles W. Moore -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

September 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

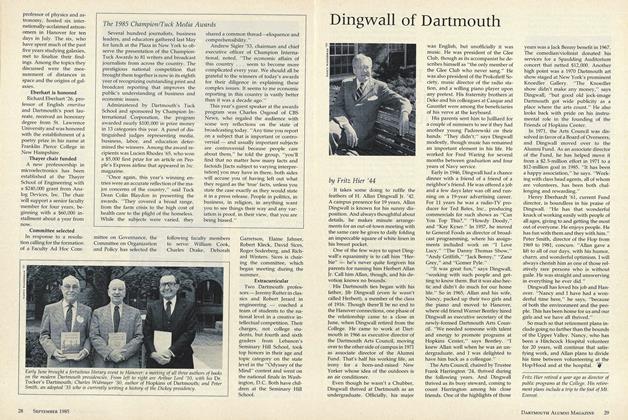

FeatureDingwall of Dartmouth

September 1985 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

September 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsMany Sighs and Many Tears

September 1985 By Jim Kenyon

Peggy Sadler

-

Feature

FeatureMaking it Happen

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Article

ArticleJay Weinberg '40 has a CAN-do attitude

NOVEMBER 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Article

ArticleLover of parades

DECEMBER 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Article

ArticleLes Nichols '40 leads nostalgic tours of Normandy

MAY 1985 By Peggy Sadler -

Article

ArticleJack Turco: Promoter of "wellness"

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Peggy Sadler -

Article

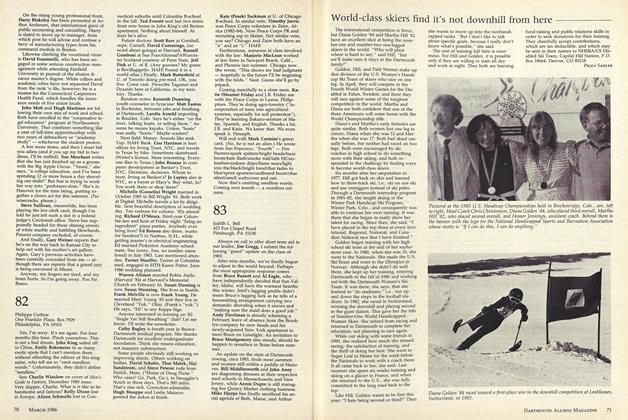

ArticleWorld-class skiers find it's not downhill from here

MARCH • 1986 By Peggy Sadler