When Emily Blackwell applied for admission to Dartmouth Medical School in 1852, the school might have made history by admitting her. But though women physicians were fairly common during the 19th century, there were no female medical students at Dartmouth until more than 100 years later, when women once again entered the field in significant numbers.

One of Dartmouth's early women medical students spoke on campus recently. Dr. Karen Hein, a former member of the DMS Board of Overseers, traced the history of women in medicine at Dartmouth. Many in the audience for her talk were first-year medical students -members of the school's historic first class in which male and female numbers are equal. During Hein's years at Dartmouth Med School, 1966 to 1968, women made up only ten percent of the student body.

Hein noted that between the application of Emily Blackwell (sister of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to graduate from medical school in the United States, in 1849) and the admission of the first woman to Dartmouth Medical School, 108 years went by. During that period, she said, the number of women physicians increased greatly in the 19th century, dwindled drastically in the early 20th century, and finally began a precipitous upswing in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

That curve was affected by a number of factors. Medicine of the 1800s was largely holistic, and approaches such as botanies and hydrotherapy, now out of fashion, were common then. In the late 1800s, onefifth of all hydropaths were women. Also, medical practice at the time was not a career to which the most gifted aspired, Hein said. It was not till 1871 that the study of medicine began to be upgraded. That year, Harvard improved its program and started paying salaries to its professors. And as professionalism increased, so did the economic rewards, making the field more attractive to men. Concomitantly, many of the holistic tasks traditionally performed by women physicians were dropped from the role of the professional physician.

In 1910, six percent of all physicians in the United States were women, Hein said. In succeeding decades, women virtually disappeared from the medical scene and that percentage was not reached again until the early 1950s. Dartmouth tested the waters in 1928 with its first woman medical faculty member, Dr. Helen Pittman. Two more followed in one-year posts in the mid-thirties, but nearly 20 years passed until the appointment of Dr. Janet Ordway in 1951-52. The number of women faculty at Dartmouth Medical School increased slower than the national average, said Hein, and the decision in 1956 to admit women students was well behind the national average. By 1984, however, when 32 percent of all medical students in the country were women, Dartmouth, with 40 percent, had surged ahead and continues to do so, Hein noted.

She also said recent years have seen advances in the attitude toward women students here. She pointed, among many indicators, to the inclusion of women's roles in medicine in a course on the history of medicine. "This is important," she said. "History can help us to understand how we got here and perhaps to avoid some of the pitfalls of the past."

Hein received her M.D. from Columbia in 1970. A recognized expert on health care for adolescent women, she is associate professor of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York and associate director of pediatric ambulatory care at Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx.

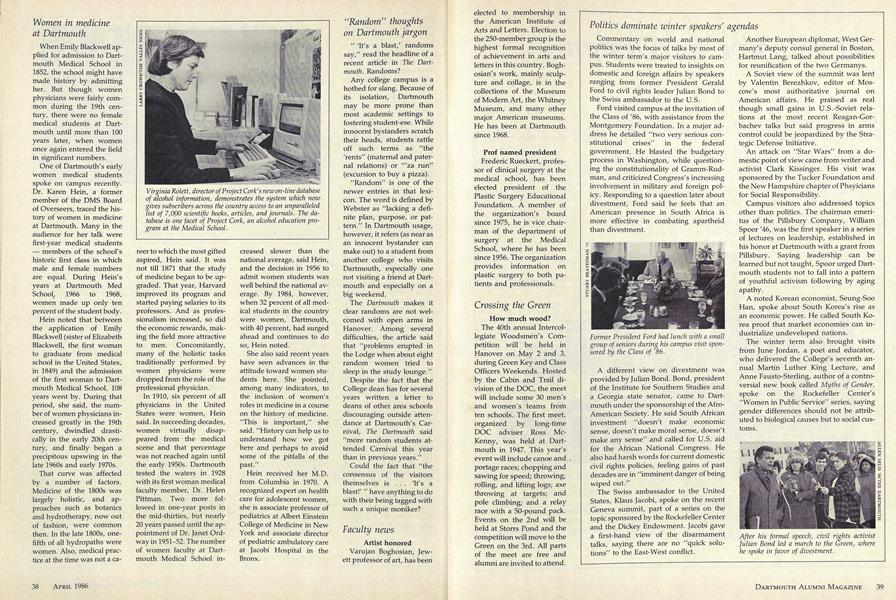

Virginia Rolett, director of Project Cork's new on-line databaseof alcohol information, demonstrates the system which nowgives subscribers across the country access to an unparalleledlist of 7,000 scientific books, articles, and journals. The database is one facet of Project Cork, an alcohol education program at the Medical School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Peace Corps at 25

April 1986 By Laura T. Hammel -

Feature

FeatureSTRATS

April 1986 By Willem Lange -

Feature

FeatureRecent Accessions in European and Graphic Art at The Hood

April 1986 By Hilliard T. Goldfarb -

Article

Article"Kiki" McCanna: Steward of Sanborn

April 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleRave Reviews?

April 1986 By Dorothy L. Foley '86 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1986 By Richard A. Masterson