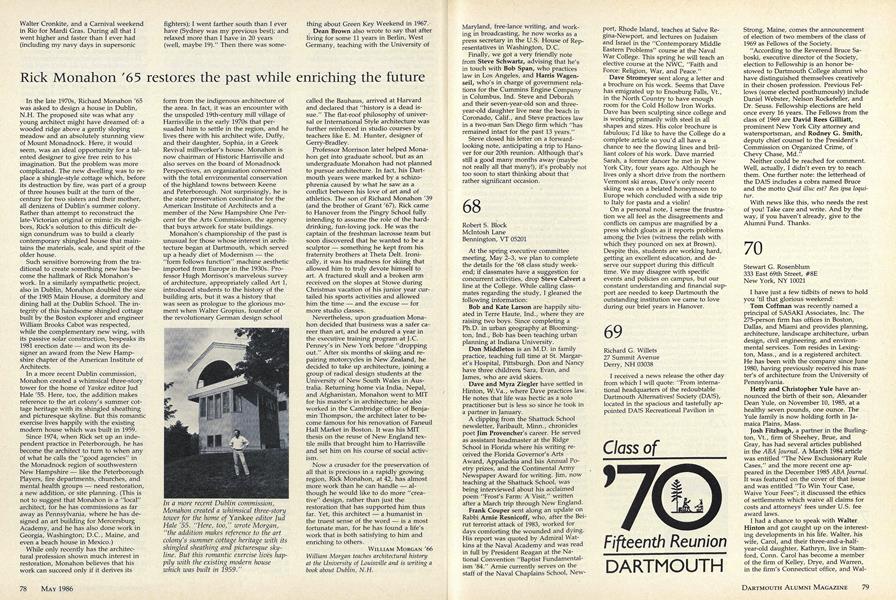

In the late 19705, Richard Monahon '65 was asked to design a house in Dublin, N.H. The proposed site was what any young architect might have dreamed of: a wooded ridge above a gently sloping meadow and an absolutely stunning view of Mount Monadnock. Here, it would seem, was an ideal opportunity for a talented designer to give free rein to his imagination. But the problem was more complicated. The new dwelling was to replace a shingle-style cottage which, before its destruction by fire, was part of a group of three houses built at the turn of the century for two sisters and their mother, all denizens of Dublin's summer colony. Rather than attempt to reconstruct the late-Victorian original or mimic its neighbors, Rick's solution to this difficult design conundrum was to build a clearly contemporary shingled house that maintains the materials, scale, and spirit of the older house.

Such sensitive borrowing from the traditional to create something new has become the hallmark of Rick Monahon's work. In a similarly sympathetic project, also in Dublin, Monahon doubled the size of the 1905 Main House, a dormitory and dining hall at the Dublin School. The integrity of this handsome shingled cottage built by the Boston explorer and engineer William Brooks Cabot was respected, while the complementary new wing, with its passive solar construction, bespeaks its 1981 erection date — and won its designer an award from the New Hampshire chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

In a more recent Dublin commission, Monahon created a whimsical three-story tower for the home of Yankee editor Jud Hale '55. Here, too, the addition makes reference to the art colony's summer cottage heritage with its shingled sheathing and picturesque skyline. But this romantic exercise lives happily with, the existing modern house which was built in 1959.

Since 1974, when Rick set up an independent practice in Peterborough, he has become the architect to turn to when any of what he calls the "good agencies" in the Monadnock region of southwestern New Hampshire - like the Peterborough Players, fire departments, churches, and mental health groups - need restoration, a new addition, or site planning. (This is not to suggest that Monahon is a "local" architect, for he has commissions as far away as Pennsylvania, where he has designed an art building for Mercersburg Academy, and he has also done work in Georgia, Washington, D.C., Maine, and even a beach house in Mexico.)

While only recently has the architectural profession shown much interest in restoration, Monahon believes that his work can succeed only if it derives its form from the indigenous architecture of the area. In fact, it was an encounter with the unspoiled 19th-century mill village of Harrisville in the early 1970s that persuaded him to settle in the region, and he lives there with his architect wife, Duffy, and their daughter, Sophia, in a Greek Revival millworker's house. Monahon is now chairman of Historic Harrisville and also serves on the board of Monadnock Perspectives, an organization concerned with the total environmental conservation of the highland towns between Keene and Peterborough. Not surprisingly, he is the state preservation coordinator for the American Institute of Architects and a member of the New Hampshire One Percent for the Arts Commission, the agency that buys artwork for state buildings.

Monahon's championship of the past is unusual for those whose interest in architecture began at Dartmouth, which served up a heady diet of Modernism - the "form follows function" machine aesthetic imported from Europe in the 19305. Professor Hugh Morrison's marvelous survey of architecture, appropriately called Art 1, introduced students to the history of the building arts, but it was a history that was seen as prologue to the glorious moment when Walter Gropius, founder of the revolutionary German design school called the Bauhaus, arrived at Harvard and declared that "history is a dead issue." The flat-roof philosophy of universal or International Style architecture was further reinforced in studio courses by teachers like E. M. Hunter, designer of Gerry-Bradley.

Professor Morrison later helped Monahon get into graduate school, but as an undergraduate Monahon had not planned to pursue architecture. In fact, his Dart- mouth years were marked by a schizophrenia caused by what he saw as a conflict between his love of art and of athletics. The son of Richard Monahon '39 (and the brother of Grant '67), Rick came to Hanover from the Pingry School fully intending to assume the role of the harddrinking, fun-loving jock. He was the captain of the freshman lacrosse team but soon discovered that he wanted to be a sculptor - something he kept from his fraternity brothers at Theta Delt. Ironically, it was his madness for skiing that allowed him to truly devote himself to art. A fractured skull and a broken arm received on the slopes at Stowe during Christmas vacation of his junior year curtailed his sports activities and allowed him the time - and the excuse - for more studio classes.

Nevertheless, upon graduation Monahon decided that business was a safer career than art, and he endured a year in the executive training program at J.C. Penney's in New York before "dropping out." After six months of skiing and repairing motorcycles in New Zealand, he decided to take up architecture, joining a group of radical design students at the University of New South Wales in Australia. Returning home via India, Nepal, and Afghanistan, Monahon went to MIT for his master's in architecture; he also worked in the Cambridge office of Benjamin Thompson, the architect later to become famous for his renovation of Faneuil Hall Market in Boston. It was his MIT thesis on the reuse of New England textile mills that brought him to Harrisville and set him on his course of social activism.

Now a crusader for the preservation of all that is precious in a rapidly growing region, Rick Monahon, at 42, has almost more work than he can handle - although he would like to do more "creative" design, rather than just the restoration that has supported him thus far. Yet, this architect - a humanist in the truest sense of the word - is a most fortunate man, for he has found a life's work that is both satisfying to him and enriching to others.

In a more recent Dublin commission,Monahon created a whimsical three-storytower for the home of Yankee editor JudHale '55. "Here, too," wrote Morgan,"the addition makes reference to the artcolony's summer cottage heritage with itsshingled sheathing and picturesque sky-line. But this romantic exercise lives happily with the existing modern housewhich was built in 1959."

William Morgan teaches architectural historyat the University of Louisville and is writing abook about Dublin, N.H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

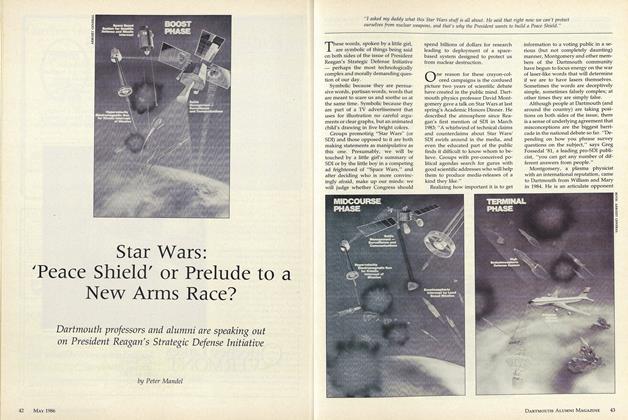

FeatureStar Wars: 'Peace Shield' or Prelude to a New Arms Race?

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Feature

FeatureNative Americans at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

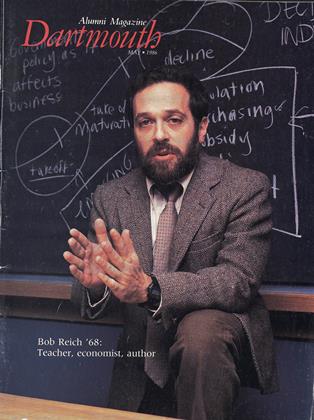

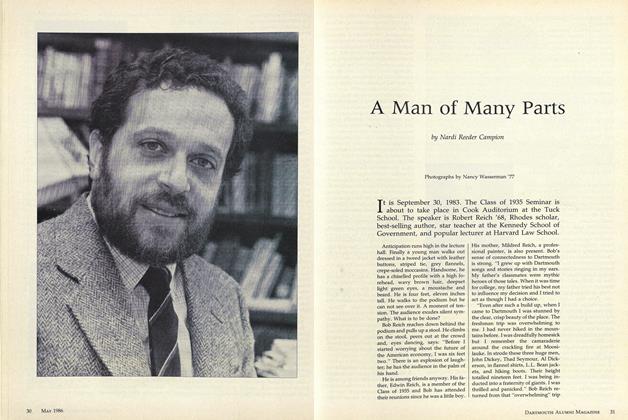

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

May 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleBack where it all began: Al McGuire at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

May 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

ArticleErich Kunzel '57: The prince of pops

May 1986 By Daniel T. DiMuzio '81

WILLIAM MORGAN '66

Article

-

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1925 -

Article

Article"A BUILDER OF A DREAM DARTMOUTH"

MARCH, 1928 -

Article

ArticleRepresentatives of the College at Recent Academic Occasions

January 1940 -

Article

ArticleJoys in the Mood

APRIL 1997 -

Article

ArticleScientific Politics or Political Science?

May 1995 By Amit Chibber '97 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

April 1940 By The Editor