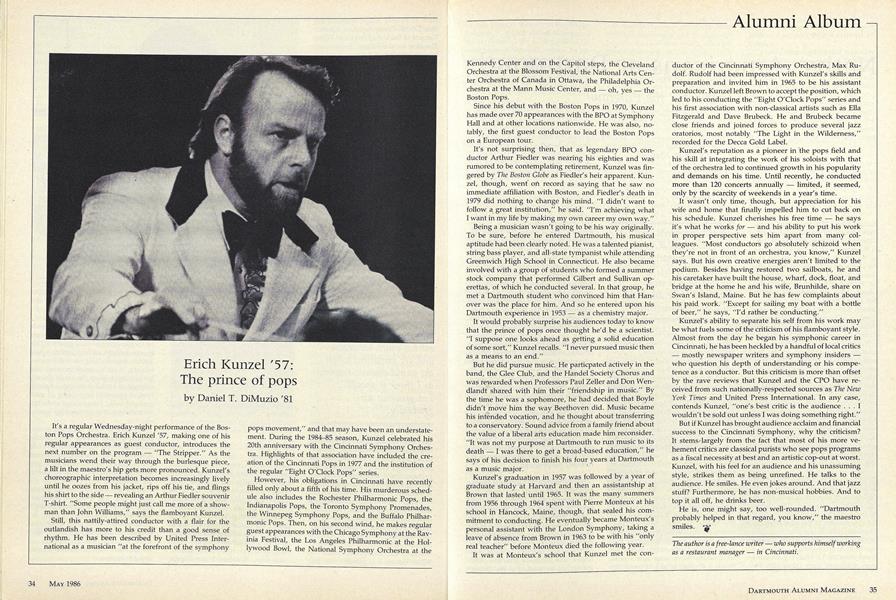

It's a regular Wednesday-night performance of the Boston Pops Orchestra. Erich Kunzel '57, making one of his regular appearances as guest conductor, introduces the next number on the program - "The Stripper." As the musicians wend their way through the burlesque piece, a lilt in the maestro's hip gets more pronounced. Kunzel's choreographic interpretation becomes increasingly lively until he oozes from his jacket, rips off his tie, and flings his shirt to the side - revealing an Arthur Fiedler souvenir T-shirt. "Some people might just call me more of a showman than John Williams," says the flamboyant Kunzel.

Still, this nattily-attired conductor with a flair for the outlandish has more to his credit than a good sense of rhythm. He has been described by United Press International as a musician "at the forefront of the symphony pops movement," and that may have been an understatement. During the 1984-85 season, Kunzel celebrated his 20th anniversary with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Highlights of that association have included the creation of the Cincinnati Pops in 1977 and the institution of the regular "Eight O'Clock Pops" series.

However, his obligations in Cincinnati have recently filled only about a fifth of his time. His murderous schedule also includes the Rochester Philharmonic Pops, the Indianapolis Pops, the Toronto Symphony Promenades, the Winnepeg Symphony Pops, and the Buffalo Philharmonic Pops. Then, on his second wind, he makes regular guest appearances with the Chicago Symphony at the Ravinia Festival, the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, the National Symphony Orchestra at the Kennedy Center and on the Capitol steps, the Cleveland Orchestra at the Blossom Festival, the National Arts Center Orchestra of Canada in Ottawa, the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Mann Music Center, and - oh, yes - the Boston Pops.

Since his debut with the Boston Pops in 1970, Kunzel has made over 70 appearances with the BPO at Symphony Hall and at other locations nationwide. He was also, notably, the first guest conductor to lead the Boston Pops on a European tour.

It's not surprising then, that as legendary BPO conductor Arthur Fiedler was nearing his eighties and was rumored to be contemplating retirement, Kunzel was fingered by The Boston Globe as Fiedler's heir apparent. Kunzel, though, went oh record as saying that he saw no immediate affiliation with Boston, and Fiedler's death in 1979 did nothing to change his mind. "I didn't want to follow a great institution," he said. "I'm achieving what I want in my life by making my own career my own way."

Being a musician wasn't going to be his way originally. To be sure, before he entered Dartmouth, his musical aptitude had been clearly noted. He was a talented pianist, string bass player, and all-state tympanist while attending Greenwich High School in Connecticut. He also became involved with a group of students who formed a summer stock company that performed Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, of which he conducted several. In that group, he met a Dartmouth student who convinced him that Hanover was the place for him. And so he entered upon his Dartmouth experience in 1953 as a chemistry major.

It would probably surprise his audiences today to know that the prince of pops once thought he'd be a scientist. "I suppose one looks ahead as getting a solid education of some sort," Kunzel recalls. "I never pursued music then as a means to an end."

But he did pursue music. He particpated actively in the band, the Glee Club, and the Handel Society Chorus and was rewarded when Professors Paul Zeller and Don Wendlandt shared with him their "friendship in music." By the time he was a sophomore, he had decided that Boyle didn't move him the way Beethoven did. Music became his intended vocation, and he thought about transferring to a conservatory. Sound advice from a family friend about the value of a liberal arts education made him reconsider. "It was not my purpose at Dartmouth to run music to its death - I was there to get a broad-based education," he says of his decision to finish his four years at Dartmouth as a music major.

Kunzel's graduation in 1957 was followed by a year of graduate study at Harvard and then an assistantship at Brown that lasted until 1965. It was the many summers from 1956 through 1964 spent with Pierre Monteux at his school in Hancock, Maine, though, that sealed his commitment to conducting. He eventually became Monteux's personal assistant with the London Symphony, taking a leave of absence from Brown in 1963 to be with his "only real teacher" before Monteux died the following year.

It was at Monteux's school that Kunzel met the conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Max Rudolf. Rudolf had been impressed with Kunzel's skills and preparation and invited him in 1965 to be his assistant conductor. Kunzel left Brown to accept the position, which led to his conducting the "Eight O'Clock Pops" series and his first association with non-classical artists such as Ella Fitzgerald and Dave Brubeck. He and Brubeck became close friends and joined forces to produce several jazz oratorios, most notably "The Light in the Wilderness," recorded for the Decca Gold Label.

Kunzel's reputation as a pioneer in the pops field and his skill at integrating the work of his soloists with that of the orchestra led to continued growth in his popularity and demands on his time. Until recently, he conducted more than 120 concerts annually - limited, it seemed, only by the scarcity of weekends in a year's time.

It wasn't only time, though, but appreciation for his wife and home that finally impelled him to cut back on his schedule. Kunzel cherishes his free time - he says it's what he works for - and his ability to put his work in proper perspective sets him apart from many colleagues. "Most conductors go absolutely schizoid when they're not in front of an orchestra, you know," Kunzel says. But his own creative energies aren't limited to the podium. Besides having restored two sailboats, he and his caretaker have built the house, wharf, dock, float, and bridge at the home he and his wife, Brunhilde, share on Swan's Island, Maine. But he has few complaints about his paid work. "Except for sailing my boat with a bottle of beer," he says, "I'd rather be conducting."

Kunzel's ability to separate his self from his work may be what fuels some of the criticism of his flamboyant style. Almost from the day he began his symphonic career in Cincinnati, he has been heckled by a handful of local critics - mostly newspaper writers and symphony insiders - who question his depth of understanding or his competence as a conductor. But this criticism is more than offset by the rave reviews that Kunzel and the CPO have received from such nationally-respected sources as The NewYork Times and United Press International. In any case, contends Kunzel, "one's best critic is the audience ... I wouldn't be sold out unless I was doing something right."

But if Kunzel has brought audience acclaim and financial success to the Cincinnati Symphony, why the criticism? It stems largely from the fact that most of his more vehement critics are classical purists who see pops programs as a fiscal necessity at best and an artistic cop-out at worst. Kunzel, with his feel for an audience and his unassuming style, strikes them as being unrefined. He talks to the audience. He smiles. He even jokes around. And that jazz stuff? Furthermore, he has non-musical hobbies. And to top it all off, he drinks beer.

He is, one might say, too well-rounded. "Dartmouth probably helped in that regard, you know," the maestro smiles,

The author is a free-lance writer - who supports himself workingas a restaurant manager - in Cincinnati.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

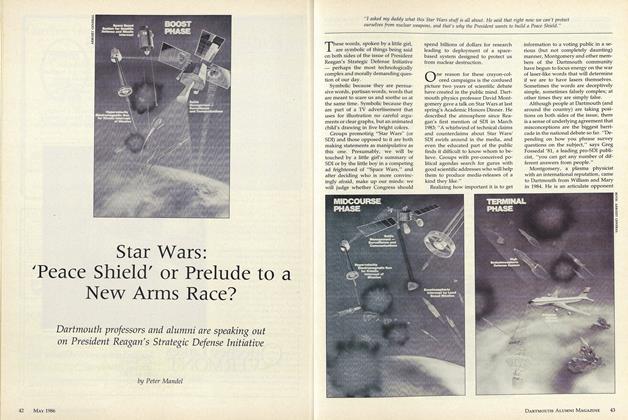

FeatureStar Wars: 'Peace Shield' or Prelude to a New Arms Race?

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Feature

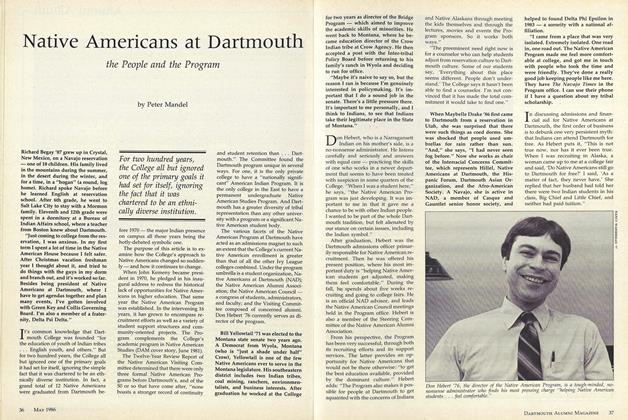

FeatureNative Americans at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Cover Story

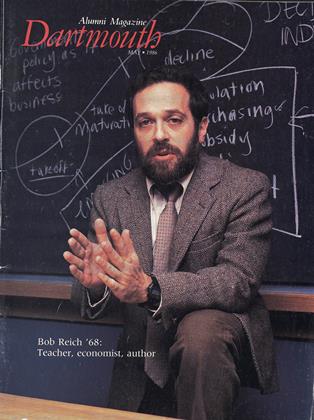

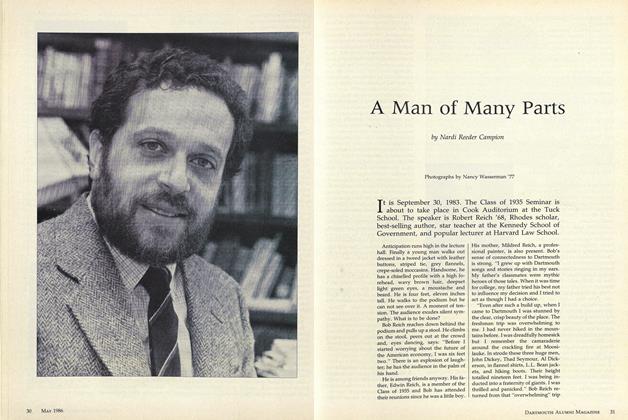

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

May 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleBack where it all began: Al McGuire at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

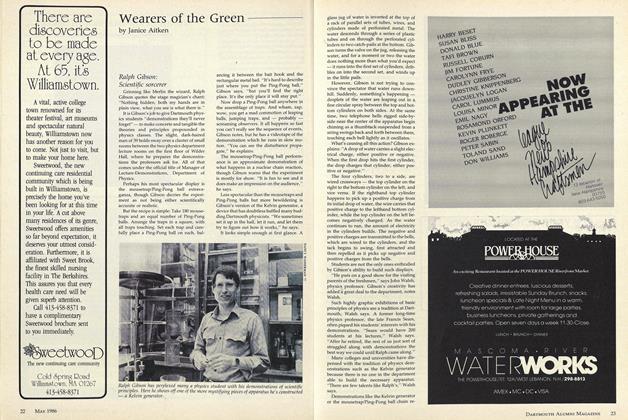

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

May 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

ArticleRick Monahon '65 restores the past while enriching the future

May 1986 By WILLIAM MORGAN '66