Perhaps the powerhouse schools should study the Ivies, where success and scandal don't go hand in hand.

On June 30, 1987, in Dallas, the NCAA launched a "National Forum" on intercollegiate athletics that will debate educational-athletic issues through 1988. Ira Heyman '54, Chancellor of the University of California-Berkeley and a trustee at Dartmouth, kicked off these discussions by reviewing a litany of scandals and decrying the overcommercialization of big-time sports. His solutions included financial aid based on need, not on athletic prowess; freshman ineligibility; and a more egalitarian dispersal of the tremendous revenues derived through intercollegiate athletics. Does this sound familiar?

Integrity

The similarities between Ivy athletics and bigtime athletics are compelling: our students and coaches want to win very much; we've had our share of successes nationally and have produced many professional and Olympic competitors. Nationally and in the Ivies, athletics serve valuable institutional priorities—they are important.

There are major differences, however. No Ivy school has been subjected to a scandal of the magnitude we now find common in big-time athletics. Our athletes are students first, graduating and undertaking professional and graduate training at the same rate as their peers. They are all true amateurs, playing for the love of sport, their teammates and their college, not for pay or in pursuit of professional aspirations. The Ivies are also different because the public perceives us as different: the athletic conference known as the Ivy Group gives the graduates of our eight schools a stamp that means integrity in athletics.

Solid Philosophy

A recent survey of NCAA chief executive officers showed that 99 percent were concerned about the current state of integrity in college athletics. Until institutions develop a coherent, sound, and articulated philosophy of academics first and athletics second, the NCAA and her institutions will continue to suffer from a hole-in-the-dike mentality, struggling to resist the overwhelming pressure to win. More rules, more regulations, more attempts at enforcement will be the result.

The Ivies, on the other hand, developed a solid philosophy in 1954: students will be admitted on the basis of their academic performance, not their athletic talent; there will be no athletic grants-inaid; athletic schedules will be developed only after academic concerns are addressed. We're different, then, because we have a philosophy that is adhered to and believed by each institution, its coaches, its athletes and its alumni.

Academics First

Special admissions procedures, special tutoring, special curriculums designed toward maintaining eligibility are all too common in big-time athletics. This is not the case in the Ivies. Most of the problems in intercollegiate athletics could be handled, according to Andy Geiger, former Ivy Group athletic director and now director of athletics at Stanford, if the admissions officers would do their job and allow only those student athletes to matriculate who are academically motivated and interested enough to do the work.

Since 1954, the playing seasons and practice schedules of the Ivy Group have been severely constricted. Games and practices are scheduled to avoid missed class time and are generally prohibited during reading and final exam periods.

While the stereotype of the "dumb jock" will never go away completely, both the fact and the feeling on the Ivy campuses is that Ivy athletes are truly representative of their classes. This contributes to the feeling of self-worth of our athletes and helps eliminate resentment on the part of students and faculty toward coddled athletes.

Arms Race

In the Ivy League schools, financial support is justified by the belief that athletics contribute to the education of students, while many big-time programs that emphasize entertainment and commercialism lack justification for using institutional funds to offset costs. The Ivy programs benefit from these funds in two ways: the pressure to win for the sake of income is reduced, and the athletic budget is subject to institutional review.

In big-time athletics, the more you win the more the pressure mounts. Each finalist in the NCAA final four basketball tournament received more than $1 million specifically because it had a great team. Big-time athletics has become an arms race in which new weight rooms, indoor football practice facilities, and new carpeting in the coach's office all become the norm. If going to a bowl game means a million-plus profit to the institution, what's another $200,000 for a non-educationally related item that adds enough glamor to attract that special player who might have a high impact?

In the Ivy group the institutional financial support of intercollegiate athletics has been subjected to the same scrutiny and guidelines as other academic programs. This type of oversight has reduced pressure to increase income and has also helped to diminish the big-time athletics arms race in terms of dollars spent. When an athletic department is a separate corporation only loosely affiliated with the institution, it is not necessarily subject to this type of review.

Sneakered Stars

At Dartmouth College, approximately 1,500 students out of a student body of 4,000 participate in intercollegiate athletics every year. The numbers are similar across the Ivy Group. Conversely, Ohio State has approximately 1,000 athletes and a student population of 56,000. On a national basis, while the number of teams participating in all sports in NCAA Division I has increased over the past 15 years, the number of participants has declined. Between 1977 and 1982 NCAA figures show a 15-percent increase in the number of teams fielded in the major ten sports—along with a 17-percent decline in the number of participants in those sports. The drive for national prominence has eliminated the interest in broad participation. In other words, if you have only $100 to spend in intercollegiate athletics, why not fund one $100 superstar rather than ten students motivated by the true spirit of athletic competition?

This emphasis on the highly identifiable, highly valuable individual superstar is a reason why recruiting violations are now so numerous. If your basketball program spends $750,000 a year and has the potential to reap millions upon reaching the Final Four, what's a shortcut or two to get that special athlete who everyone knows will get you one sneaker closer to a national television contract?

Oversight

The Ivy agreement really began as a concept in 1945 with football but was formalized in 1954 for all sports. Since that time, the presidents of the Ivy Group have met to discuss athletic issues at least two or three times a year. But only recently have other college presidents become active in the governance of intercollegiate athletics. The Ivies are different because the Ivy presidents are in good shape to struggle with tradeoffs between athletics and academics, having worked consistently through the years to maintain a healthy balance.

Philosophical Change

It will take time and strong leadership for NCAA athletics to become like Ivy League athletics. A sound philosophy must be developed and accepted by all interested parties. Alumni who derive tremendous ego-gratification from their alma mater's powerhouse football team must find pride in coming from a fine academic institution where football happens to be played.

By focusing on the individual student, big-time institutions can become more like us. This may be impossible among the larger universities. But the first big step will be to reverse the alarming trends of the past few decades: commercialism, stardom, and jock-coddling. A school can choose between many quasi-professional activities to offer its students: it can operate a hotel, run a golf course, or even sponsor the New England Patriots. What we choose to sponsor, however, should be closely related to the educational impact on students or to the expansion of the perimeters of knowledge. The more the investment is in entertainment and ego, the less the institution should be involved.

Ted Leland has been Dartmouth's athletic director since1983. A sports psychologist by training, he is also adjunct professor of psychology.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSETTING FREE THE MARKET

October 1987 By Tyler Bridges -

Feature

FeatureBuilding a Better Student Body

October 1987 By Thurman Zick -

Cover Story

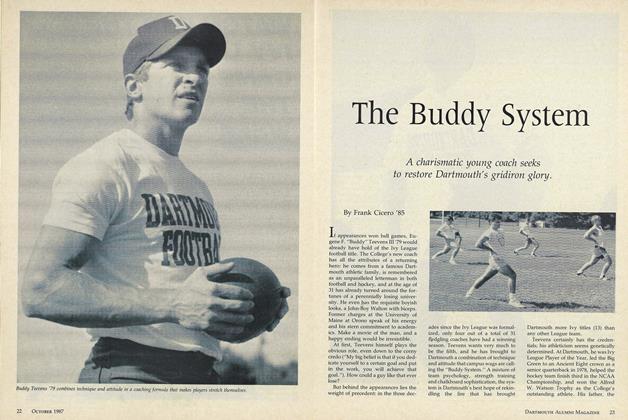

Cover StoryThe Buddy System

October 1987 By Frank Cicero '85 -

Feature

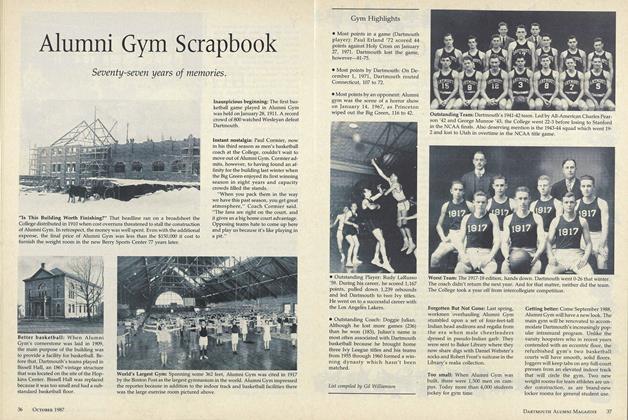

FeatureAlumni Gym Scrapbook

October 1987 By Gil Williamson -

Feature

FeatureBad Things You Learned in Gym

October 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

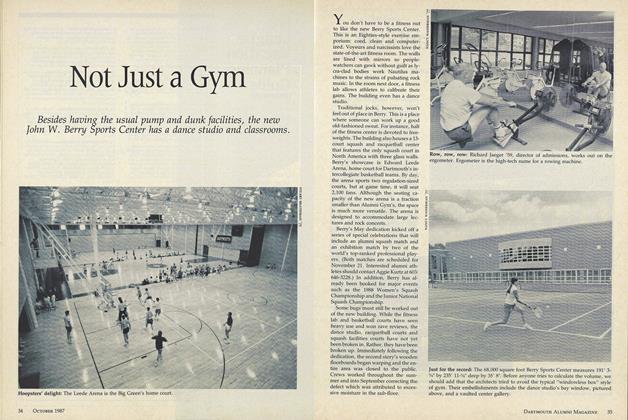

FeatureNot Just a Gym

October 1987

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureA Special Teacher

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Feature

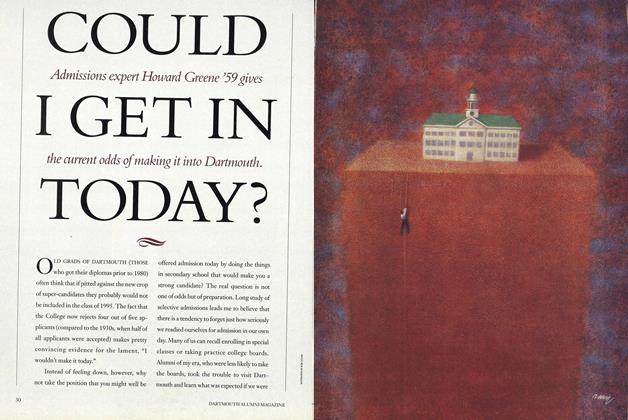

FeatureCOULD I GET IN TODAY?

APRIL 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryQuite Good

MARCH 1995 By Abner Oakes IV '81 -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62 -

Feature

FeatureThe Outing Club at 75

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Willem Lange