The desire to perspire, and how it has changed over the years.

An old grad might look around the glittering new Berry Sports Center and ask, "Where are the Indian clubs of yesteryear? These days who knows how to do the Coffee Grind or the Mill Wheel? Who hurls the medicine ball? Where lurk the straining practitioners of calisthenics, the aficionados of the duck walk, the deep knee bend, the sit-up and the toe-touch?"

Gone. All to the attic of sports history along with Roman chariot racing, quoits and the Mayan game of pok-a-tok.

In their place is the brave new world of lifelong fitness and health achieved through aerobic exercise, carryover sports and sensible nutrition. It's also the world of hot-pink spandex designer running tights in surrealist patterns, computer-engineered footwear (sneakers are up there with the quoits), sports watches that monitor your pulse rate and sports psychoanalysis for weekend hackers who fear they're in too deep.

If you spent your Dartmouth gym days dressed in woolen tights while a hawk-eyed instructor barked, "Wand forward upward—Swing!" or, a few decades later, stood in your damp grey sweat suit listening to "Awright, awright, let's see a little team spirit here!" and you have spent the successive years doing nothing more energetic than lift a gin rickey to your lips while you loll in a hammock and try to forget, the following guide will take you into the new stuff. And Dartmouth is on the leading edge of that new stuff with programs to rouse even the most supine. The only thing missing is Alumni Aerobics Via College Satellite. Who knows? It may be next.

The idea of physical education hardly existed in Dartmouth's early history, although Noah Webster stated in 1790 in his "Address to Yung Gentlemen" that it is "the bizzness of yung persons to assist nature, and strengthen the growing frame by athletic exercises." (Now we know why he wanted a dictionary.) Dartmouth got into physical education in 1866 when George H. Bissell '45 pledged $15,000 for a granite gymnasium equipped with six bowling alleys. Bissell, who started out as a poor local boy, made one of the first Pennsylvania oil fortunes. His preoccupation with bowling alleys was apparently tied to disciplinary difficulties he had suffered in undergraduate days from indulgence in that then-forbidden exercise.

The new Bissell gym opened to students in the spring of 1867. F.G. Welch, a gymnastics teacher from Yale, was hired to require students to bend and stretch under his cold eye four days a week.

At first things went reasonably well. Dr. Dixi Crosby, the resident medical professor, wrote enthusiastically, "There has been a manifest improvement in the physical tone of the college, and the increasing muscular power and agility of the young men have forced themselves on the attention even of unpracticed eyes. I am fully satisfied that these exercises have greatly subserved the general health of the students."

But the glow quickly faded. The gymnastics were tiresome; the requirement, excessive. There was a student outcry, and the required exercise days were reduced by two. In a few years the program was in shambles. Faculty records are punctuated with notes of disciplinary action, disorder and indifference in the matter of gymnastics. Until 1892 physical education classes for freshmen and sophomores dragged on, taught by a professor of mathematics on a volunteer basis whenever he could manage. Through all of this the bowling alleys were popular and well-patronized.

But the tide turned, and in 1909 the cornerstone was laid for the new gymnasium, now known as Alumni Gym, designed by the new physical education director John W. Bowler. This edifice, hailed by The Manchester Union as "FIRST OF KIND TO BE BUILT IN COUNTRY," had everything from an indoor track to a "swimming tank." All that was missing were bowling alleys. Dartmouth was back on track.

Somewhere around 1910 there crept into our national consciousness the radical idea that physical education was a necessary part of the development of the whole person. That unique institution, "leisure time," was entering people's lives along with the automobile, the eight-hour day, unionization and countless technological innovations, from Bakelite to refrigerators. By the twenties popular interest in athletic sports, exercise and recreation was surging like the stock market. The social aspects of sport were important, as were sporty clothes, such as tennis flannels and plus-fours. There was the feeling that physical sports should be fun—a source of relaxation and pleasure. "Wand forward, upward—Swing!"

The Depression was hard on physical education courses, and many college programs ended abruptly, excised from the curriculum by frill-cutters. But everything changed during World War II. Physical fitness prepared students for military service and was suddenly the goal of every college phys ed program. The most usual way to build that fitness was through a regimen of mass calisthenics, push-ups, rope climbs and obstacle courses. Passing the Navy V-12 Test (which kept raising the requirement ante) was every male student's goal. Medical examinations and health supervision became standard stuff. Recreational sports such as badminton, tennis and golf languished.

After the war was over the emphasis on physical fitness faded rather quickly, replaced by an avid interest in sports, especially team sports. Most colleges offered students a dozen choices—basketball, football, soccer, handball, golf, swimming, squash, tennis, volleyball, track. Even badminton made a comeback. There was a marked appreciation for those sports which had carryover value in later life, skills that could be used to put adult leisure time to good use. Leisure time, and what to do with it, was becoming a major worry in our lives.

"When I came here in 1964, team sports were very much in evidence, but we were starting to get more carryover activities," said Ken Jones, the current associate director of athletics at Dartmouth—"aquatics, tennis, squash, golf, skiing—skills you could use throughout your life." A sense of lifelong fitness and health was starting to emerge.

"In the last five to ten years, not only here at Dartmouth, but in our society, we've seen a growing awareness of the value of health and fitness," said Jones. "The body needs a certain amount of physical activity, and in our society we can go through a whole day without lifting anything or walking anywhere."

But the meaning of fitness includes a great deal more than just muscular strength. This is where coeducation has been a positive factor. "Our big push into aerobic fitness was motivated by women," said Jones. "The men were dragged in kicking and screaming, but they're finding it's fun." Coaches and players have realized the importance of aerobic exercise for building the endurance to last through a game or meet. The turning point came one summer, Jones said, when the football players found they couldn't keep up with the women in an advanced aerobic class. Resistance has been breaking down ever since.

"Organic fitness," said Jones, "means aerobic fitness, flexibility, fitness of the cardiovascular system and sports skills carried over into later years to maintain fitness through a lifetime. It means knowing how to handle stress, understanding correct diet and nutrition. One of the most important things we try to get across is that this total fitness improves the quality of life."

Physical education is still required at Dartmouth, at least three terms for each student. Only 50 percent of the Ivy League schools require it and across the nation, students in fewer than 30 percent of colleges and universities are obliged to take physical education classes in order to graduate, said Jones. Dartmouth makes phys ed mandatory, he said, because the students demand it.

A ten-year survey of the enrollment patterns of physical education classes at Dartmouth shows how sharply the interest in fitness has zoomed. In 1975-76 there were 63 students enrolled in the only aerobics course offered, a running course known as "Fitness"; in 1985-86 the enrollee figure for a much wider variety of aerobics courses had grown to 996. "Advanced Conditioning," weight lifting, nautilus and other anaerobic exercise drew 100 people in 1975-76; ten years later 321 people signed up.

Dartmouth's current commitment to organic fitness goes far beyond popular courses and the latest technology and equipment. Not only are there dozens of activities for students, from kayaking to aerobics to skiing, but there are regular lectures by registered dieticians, physicians and sports medicine specialists from Dartmouth-

Hitchcock Medical Center. But perhaps the most far-reaching and exemplary part of the total-fitness scene at Dartmouth is the FLIP program.

"FLIP," says Whit Mitchell, the program's rangy and supple director, "is an acronym for Fitness and Lifestyle Improvement Program. We started it in 1982 as a pilot program for students and employees—a noncompetitive ten-week exercise program. We had a total of 280 participants that first year." There is a pause. "This year we had 3,031 people in the program."

The program is designed for every age group and physical condition— students, the groundskeeper who lugs nursery trees off trucks, broad-fannied secretaries who sit all day, chalk-complexioned professors, elderly people. One can choose the type of workout that suits his or her needs: aerobics or aerobic dancing, weight training, water fitness, a walk/jog class, a stretchand-tone program, a special seniors program or a cardiac rehab class.

The program produces a kind of reverse hypochondriac, a fitness amateur who lovingly watches improved muscle tone, positive changes in blood chemistry, disappearing fat, slowed resting heart rate, improved cardiac efficiency, and more restful sleep.

And, of course, there are the aesthetic effects—not only the sleek new clothes of physical exercise, but the sleek new body. The goals are different from the no-pain-no-gain era, but sweat is still sweat. As Nigel Molesworth, the hero of Geoffrey Williams's School Days books, said: "Wot makes a boy healthy and splendid with giant and rippling muscles? Wot makes his torso remarkable eh? The answer is not the red ink skull and crossbones on his chest or the tattoo marks i luv maysie on his biceps. The effect is obtained by his WORK in the GYM."

Getting physical: From the Navy V-12 Test to Nautilus work-outs and the FLIP program, Dartmouth students have done it all,

Awright, meatheads: Ever wonder why Gym was a lot like basic training? UnderDartmouth's wartime program, every student underwent a physical examination and aphysical proficiency test designed to provide him with the best individual program forwar conditioning. These exercises were carried over into civilian fitness programs.

Walking the plank: During the war years the Karl B. Michael Pool was used forlearning how to jump off the side of a ship. Now it's for fun and fitness.

Get the lead out! Building bodies and camaraderie went hand-in-hand at AlumniGym, even if it meant standing on your head or working out on the parallel bars. Itcertainly added balance to life. But would these young men have turned out for anaerobic dance class if they had been asked?

Low-tech gear: Just an iron bar and a rope. No designer sweats. But the Dartmouthathlete's dedication was just as strong then as now.

Thurman Zick is a Hanover-based freelancewriter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSETTING FREE THE MARKET

October 1987 By Tyler Bridges -

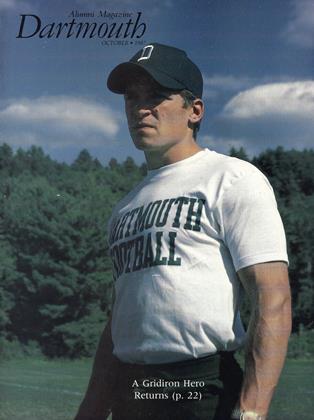

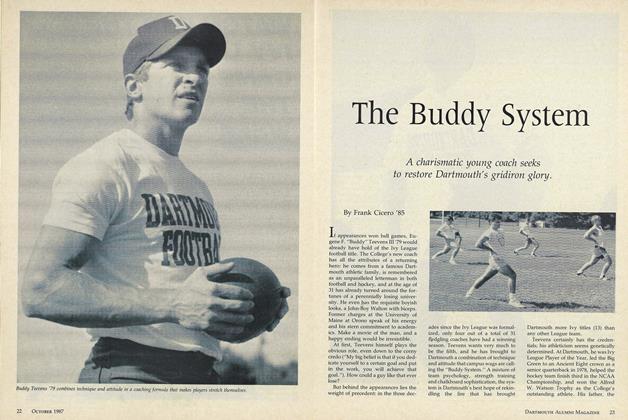

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Buddy System

October 1987 By Frank Cicero '85 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Glory?

October 1987 By Ted Leland -

Feature

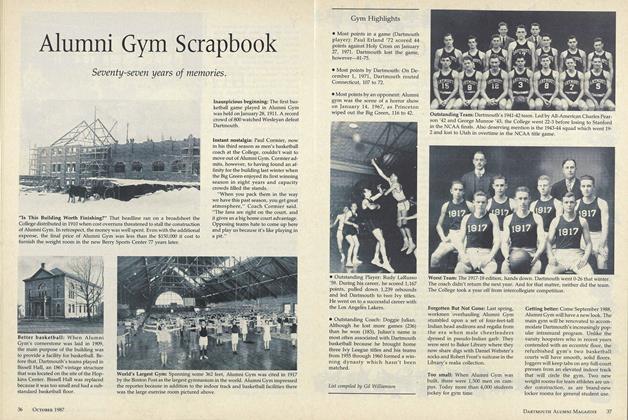

FeatureAlumni Gym Scrapbook

October 1987 By Gil Williamson -

Feature

FeatureBad Things You Learned in Gym

October 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

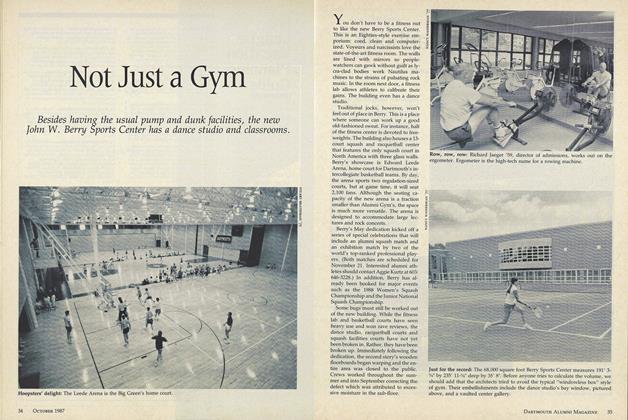

FeatureNot Just a Gym

October 1987

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryOUTING CLUB PIN

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

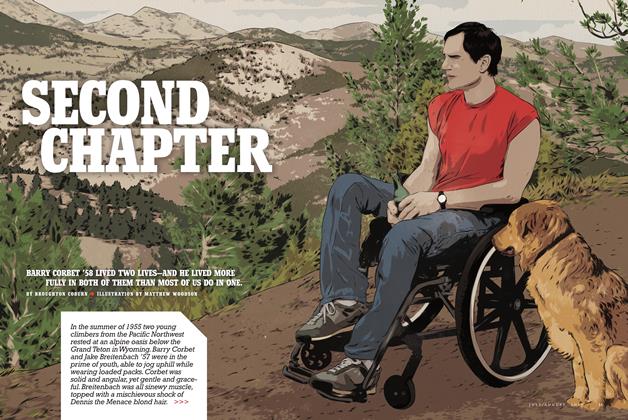

Cover StorySECOND CHAPTER

July/Aug 2013 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Feature

FeatureWomen on the Verge

Mar/Apr 2003 By Jennifer Kay ’01 -

Feature

FeatureThe Daredevil

Jan/Feb 2013 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureNATIONAL SECURITY: Issues and Prospects

December 1960 By LOUIS MORTON -

Feature

FeatureThree Staff Members Reach Retirement

JULY 1973 By ROBIN ROBINSON '24