Last spring, the editorial board of The Dartmouth voted to publish a house editorial opposing a plan to create a women's resource center on campus. That evening, before the opinion appeared in print, a small group of women came to the D demanding we not print it. They felt only women should be allowed to have an opinion on the matter and that we editors didn't realize the impact an editorial critical of the center might have on the status of women. After debating with us for a few minutes, several of the women began to cry. One woman screamed at me through her tears that I had "no right, no right."

The fact is, of course, that The Dartmouth did have a right to its opinion. It had that right then and it has it now. On a college campus, particularly one with Dartmouth's strong academic reputation, open, reasonable debate on issues affecting us is central to the intellectual process. But too often we see campus conversation degenerate into what amounts to a parochial battle for political gain. People involved in debate become and remain nothing more than emotional constituencies. They are more interested in scoring points toward the prize of having the winning opinion of the day than in embracing intellectual growth. The real ambiguousness of the terms "right" and "wrong" is forgotten; if you don't agree with us, you're wrong.

When I was in high school, I imagined college as a place where everyone was open-minded enough to accept, though not necessarily agree with, intelligent, well-articulated opinions contrary to their own. I have realized since how naive that expectation was on a campus as politicized as Dartmouth's. Where else could a debate over a single issue, the Indian symbol, continue for more than a decade?

Surely we all have our opinions firmly in place. Surely we are aware how the various self-acknowleged constituencies feel about the issue. There is no intellectual growth to be gained from continuing agitation, such as the proselytizing that goes on every fall when the pro-Indian symbol groups attempt to win the support of the freshmen. But there is the hope of a possible political win. The pit bulls of Dartmouth clamp their jaws as tightly as ever and refuse to let go until they have won.

Implicit in the erection of shanties on the Green was the admission that intellectual debate had failed once again. Unable to win the College over to their point of view on South Africa, students left the intellectual realm and took physical action. It should have come as no surprise when their counterparts on the opposite side of the political agenda decided to fight with similar tactics, using sledgehammers to destroy the shanties. Symbols fighting symbols is a sorry state of affairs.

In the debate over Dartmouth's alma mater, both sides seemed so concerned with their own interests, either keeping or jettisoning "Men of Dartmouth," that little communication went on. Both the student and the alumni committees investigating the issue have postponed making a decision. At official occasions, both versions are printed and one can choose to sing the traditional version or the contemporary, nongender-specific one.

Do traditionalists understand why women feel the need to change the song? Do women understand why many aiumni feel such a connection with the song as it was originally written? Perhaps the answer to both questions is yes, but it's more likely that each side views the other as alien and unapproachable. This should not be the case. Discourse and communication connote a coming together, a mutual understanding often bypassed on the fast track toward an expedient solution.

The day the editorial on the women's resource center appeared in The Dartmouth, there was a "speak-out" in the Top of the Hop to discuss the alleged sexism of the paper. At the forum, a woman professor took the microphone and said the paper had been wrong in its opinion. She didn't say our logic was faulty or our research flawed; she said our opinion was wrong. Her statement was as ridiculous as it was revealing. For many at Dartmouth, debate means decomposing an argument into a battle over right and wrong in the shortest amount of time. The professor at the Hop reduced the debate to nonsense from the beginning. You're wrong, I'm right. I wonder now why she didn't just stick out her tongue.

Matthew Garcia, a senior from Charlotte, NorthCarolina, is managing editor of The Dartmouth as well as a Whitney Campbell intern at the Alumni Magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTaking the Sky

November 1987 By Glenn Tremml '82 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Iran: Can We Have a Foreign Policy?

November 1987 By Stephen Bosworth '61 -

Feature

FeatureAre Conservatives Being Silenced?

November 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureRooming with Style

November 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

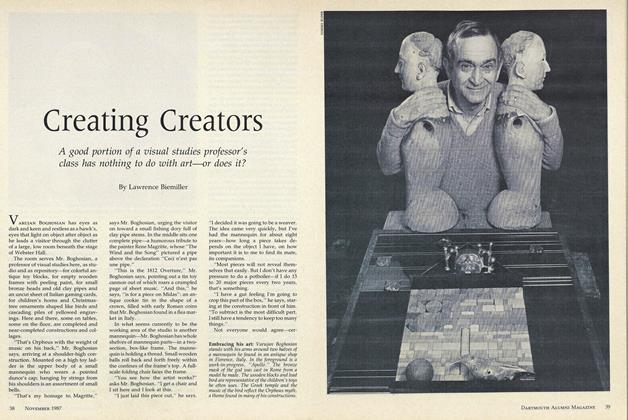

FeatureCreating Creators

November 1987 By Lawrence Biemiller -

Feature

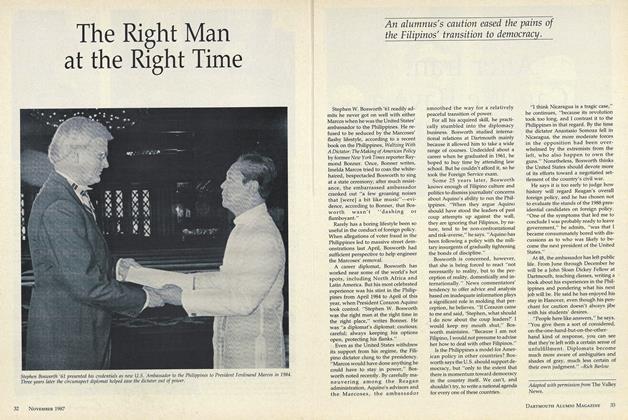

FeatureThe Right Man at the Right Time

November 1987

Article

-

Article

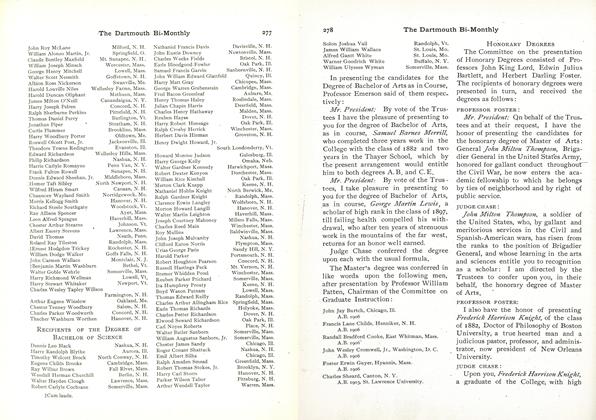

ArticleRECIPIENTS OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE

AUGUST, 1907 -

Article

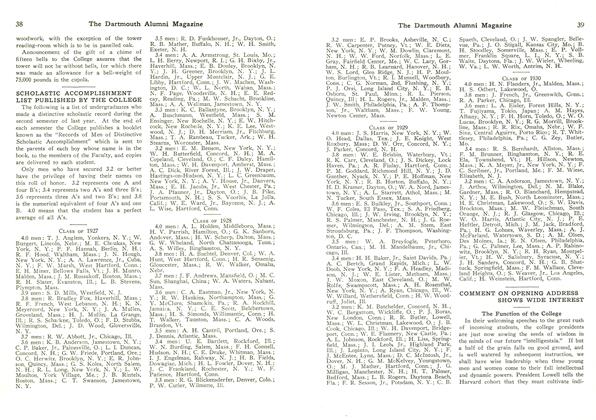

ArticleSCHOLASTIC ACCOMPLISHMENT LIST PUBLISHED BY THE COLLEGE

NOVEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleCircling the Green

JUNE 1978 -

Article

ArticleCLASS OF 2017

DECEMBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleCROSS-COUNTRY

DECEMBER 1964 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThe College

November 1978 By Professor Charles Emerson, 1890