A good portion of a visual studies professor's class has nothing to do with art-or does it?

Varujan Boghosian has eyes as dark and keen and restless as a hawk's, eyes that light on object after object as he leads a visitor through the clutter of a large, low room beneath the stage of Webster Hall.

The room serves Mr. Boghosian, a professor of visual studies here, as studio and as repository for colorful antique toy blocks, for empty wooden frames with peeling paint, for small bronze heads and old clay pipes and an uncut sheet of Italian gaming cards, for children's horns and Christmastree ornaments shaped like birds and cascading piles of yellowed engravings. Here and there, some on tables, some on the floor, are completed and near-completed constructions and collages.

"That's Orpheus with the weight of music on his back," Mr. Boghosian says, arriving at a shoulder-high construction. Mounted on a high toy ladder is the upper body of a small mannequin who wears a pointed dunce's cap; hanging by strings from his shoulders is an assortment of small bells.

"That's my homage to Magritte," says Mr. Boghosian, urging the visitor on toward a small fishing dory full of clay pipe stems. In the middle sits one complete pipe a humorous tribute to the painter Rene Magritte, whose "The Wind and the Song" pictured a pipe above the declaration "Ceci n'est pas une pipe."

"This is the 1812 Overture," Mr. Boghosian says, pointing out a tin toy cannon out of which roars a crumpled page of sheet music. "And this," he says, "is for a piece on Midas": an antique cookie tin in the shape of a crown, filled with early Roman coins that Mr. Boghosian found in a flea market in Italy.

In what seems currently to be the working area of the studio is another mannequin Mr. Boghosian has whole shelves of mannequin parts in a twosection, box-like frame. The mannequin is holding a thread. Small wooden balls roll back and forth freely within the confines of the frame's top. A fullscale folding chair faces the frame.

"You see how the artist works?" asks Mr. Boghosian. "I get a chair and I sit here and I look at this.

"I just laid this piece out," he says. "I decided it was going to be a weaver. The idea came very quickly, but I've had the mannequin for about eight years how long a piece takes depends on the object I have, on how important it is to me to find its mate, its companions.

"Most pieces will not reveal themselves that easily. But I don't have any pressure to do a potboiler if I do 15 to 20 major pieces every two years, that's something.

"I have a gut feeling I'm going to crop this part of the box," he says, staring at the construction in front of him. "To subtract is the most difficult part. I still have a tendency to keep too many things."

Not everyone would agree Certainly not those who collect his works, paying many thousands of dollars for the more elaborate ones at the New York gallery Cordier & Ekstrom. "I do very well," Mr. Boghosian admits. "Usually after they've bought one, they want more." But he spends countless hours and thousands of dollars in search of materials the colorful toy Anchor blocks that form architectural backdrops for many of his pieces are rare and expensive, for instance, and the bronze objects he uses are cast to order in Rome.

Mr. Boghosian, who calls himself a "sculptor in low relief" and sometimes also uses the word "surrealist," says he comes to the studios most evenings and on weekends, leaving outside his responsibilities as a Dartmouth faculty member and as a director of the McDowell Colony, an artists' retreat in New Hampshire. Here he populates the world with Orpheuses in the shapes of mannequins and birds and butterflies and hearts his fascination with the Orpheus myth dates back to high school, he says as well as with Plutos and Eurydices, with Punchinellos in sad poses who wear the pointed dunce's cap given them by Tiepolo, and with a host of other strange and wonderful characters.

He allows few students in. "I try to keep my work separate from theirs," he says, locking the door as he hurries off to his office in the visual studies department. "They get hypnotized with all this junk, and the next thing you know ..."

Just now Mr. Boghosian is acting chairman of the department. He finds its office besieged by students who need his signature on slips of paper admitting them to next semester's courses, by a visiting candidate for a faculty opening, and by an office-supplies salesman wooing the department's secretary, Katherine Sterling.

Mr. Boghosian deals with each in turn, telling students the best he can do is add their names to hopelessly long waiting lists ("Don't worry about a thing," he says, handing one student a peppermint from a jar on Sterling's desk. "Take one of these and go"); sending the candidate off to have coffee with another member of the department; and telling Sterling he will call someone in the dean's office about the new copier she wants ("Katherine-take this down! I think we're going to get it!" he says, cupping one hand over the mouthpiece. "Yes. The chairman's budget? Right, $2,000. Bob, you're now an honorary member of this department.") Then he heads down the hall to his own plain office to make some calls ("Sit!" he tells his visitor. "Look at books I've got to call my wife").

Students in Mr. Boghosian's section of Art 10 have been assigned to make collages, some of which are already hanging on a wall when Mr. Boghosian enters. Before he has finished taking the roll it is obvious that he enjoys teaching; the class is a catholic experience for everyone in the room.

"Where are you from?" he asks one student. "The Napa Valley? What's a good winery there? Beringer? Mark that down, class. How do you spell Beringer?" He believes in teaching students to speak out, Mr. Boghosian says, and fires questions at them until they do.

Then he begins discussing the collages. "This is certainly an extreme wall, class. Who did this remarkable piece?" A student raises his hand.

"That is a majestic background, a fantastic collection of blacks and grays. But this in the foreground just isn't enough. Put it on your wall, go to dinner, and the first thing you do when you come back, you look at it. Look at it, think about it, turn it on its side, turn it upside down. Do you understand what I mean, class? The nice thing about a collage is that you can tear it apart. Who did this? A small masterpiece, absolutely.

"But what about technique, class?" he asks, wiggling a loose piece of cardboard. "Why at this point in the class can't we find a stiff piece of board?"

Class tumbles forward.

"Does anybody not know Charles Lindbergh's name? Good. But how many of you know Brancusi's name?"

"Bring in a pretty book on de Chirico, a big fat book with colored plates. How do you spell de Chirico? Well, then do it phonetically. Ask the librarian, and you'll get it."

"I just finished reading a marvelous article on Emily Dickinson by Anthony Hecht, one of our great poets. It was about Bible riddles in Dickinson. A snake is 'A narrow Fellow in the Grass' who does what, class?"

"Occasionally rides," says a student, giving the next line.

"You get an A!" says Mr. Boghosian. "Now this I like very much except for certain parts."

"Literature is very important to my work," Mr. Boghosian says later, sipping coffee on a patio outside the campus coffee shop. It helps him to have a story in mind when he is creating a piece, he says, and he likes the continuity of working with familiar themes. But not all those who buy his constructions want to know the stories behind them.

"Content is something you have to be very careful about," he says. "Some people like the idea that there's a myth, but others don't want the Revelation because it changes the way they think about a piece.

"They don't have to know. Who needs to explain that two hearts in a collage are Orpheus and Eurydice? They can be a relationship someone's just had. It isn't necessary to explain anything that's so universal."

In "Untitled," a mannequin's face peers through a heart-shaped hole in a piece of oldwood. The piece represents Orpheus's quest for his lost love, Eurydice.

"American Sampler" is part of a series on America by Boghosian. The wooden toy blocksthat frame the piece are red, white, and blue. The bronze heart is held in place by piecesof old fishing line.

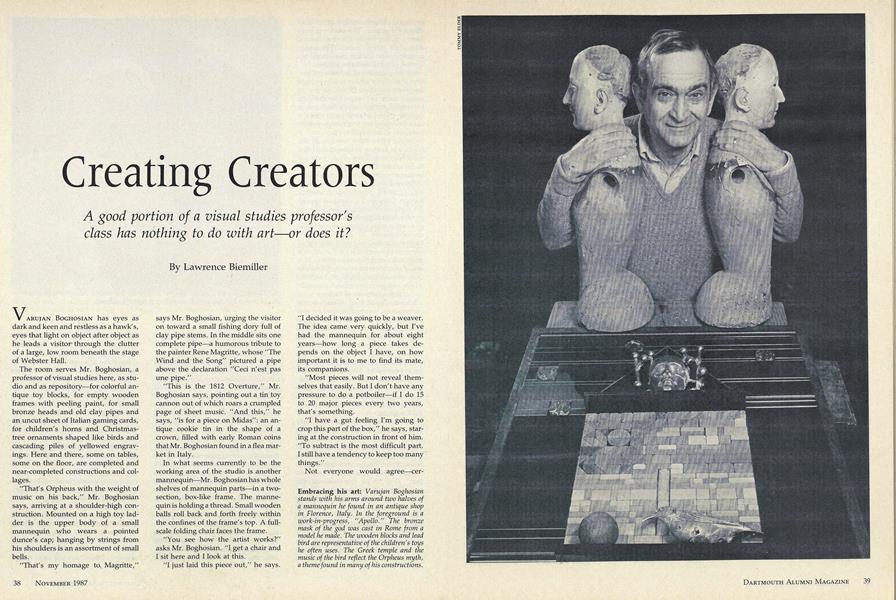

Embracing his art: Varujan Boghosianstands with his arms around two halves ofa mannequin he found in an antique shopin Florence, Italy. In the foreground is awork-in-progress, "Apollo." The bronzemask of the god was cast in Rome from amodel he made. The wooden blocks and leadbird are representative of the children's toyshe often uses. The Greek temple and themusic of the bird reflect the Orpheus myth,a theme found in many of his constructions.

Lawrence Biemiller is a Senior Writer atthe Chronicle of Higher Education. The article was reprinted with permission fromThe Chronicle of Higher Education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTaking the Sky

November 1987 By Glenn Tremml '82 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Iran: Can We Have a Foreign Policy?

November 1987 By Stephen Bosworth '61 -

Feature

FeatureAre Conservatives Being Silenced?

November 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureRooming with Style

November 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

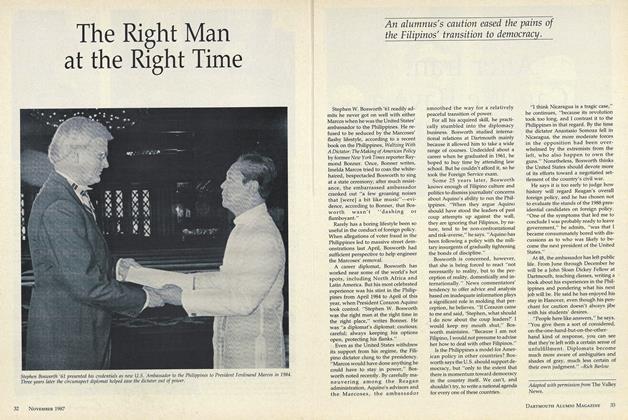

FeatureThe Right Man at the Right Time

November 1987 -

Feature

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

November 1987 By Teri Allbright

Features

-

Feature

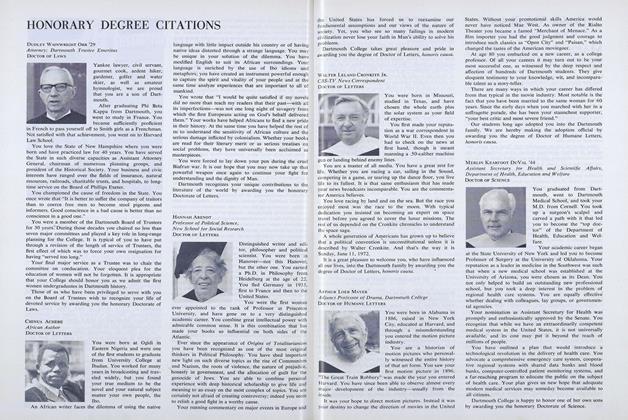

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1972 -

Feature

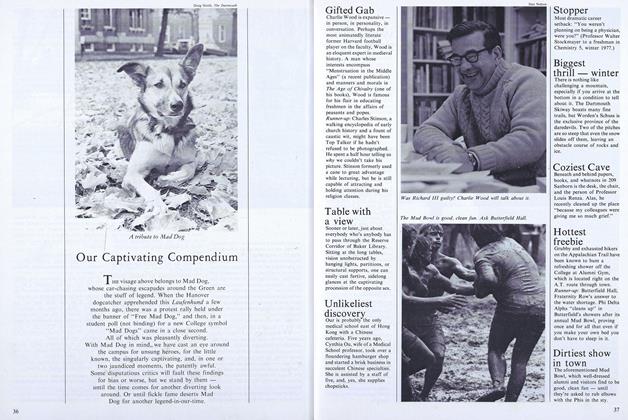

FeatureOur Captivating Compendium

APRIL 1978 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SKIWAY

January 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

NOVEMBER 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50 -

Feature

FeatureThe Bakke Case

OCT. 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2012 By Llewelynn Fletcher ’99