The Contra affair highlights the uneasy relationship between a democracy and the rest of the world, says a Dartmouth-bred diplomat.

Following the unmitigated disaster of the Iran-Contra affair, politicians and citizens alike wonder if the United States can protect our vital interests and still remain a democracy in which the makers and executors of policy are subject to accountability and the rule of law. The justification used by some of the principals in the Iran affair was that they acted in ways which, while contrary to these principles, were nonetheless necessary. And they thought it was also necessary that they hide what they were doing from the American public and the American Congress. This is not a new argument; it has long been debated whether a democracy can effectively carry out a foreign policy.

Preserving Ideals

In America's early years, Alexis de Tocqueville concluded that democracies are decidedly inferior to other governments in the conduct of foreign relations. Only with great difficulty, he said, can a democracy regulate the details of an important undertaking, persevere to a fixed design and work out its execution in spite of serious obstacles. It cannot combine its measures with secrecy or await the consequences with patience. These are qualities more likely to belong to individuals or to an aristocracy, and they are precisely the qualities by which a nation, like an individual, obtains a dominant position.

In the years during and after World War II, a quiet guerilla war has been waged for control over the formulation of American foreign policy. The war is being fought on the one hand by those who, like de Tocqueville, believe that the effective exercise of American foreign policy requires insulation from the vagaries of the American democratic process and control by a relatively small, sophisticated and experienced group-namely themselves. On the other side of the debate are those who argue that efficiency in the Exercise of foreign policy should not be obtained at the sacrifice of accountability and transparency, the basic principles of a democratic system.

The outcome of the debate will not be determined by the participants alone; a foreign policy does not exist in isolation. No matter what country, no matter what the structure of government, its international outlook comes from its national essence. It must be tied directly to identified national interests. Charles Burton Marshall defined the American national interest in the 1950s the goal of American foreign policy, he said, is to preserve in the world a situation that permits the survival of the values articulated in the preamble to the American constitution the establishment of justice, the securing of liberty, the promotion of general liberty as political realities in the United States.

Compromise Vs. Coercion

The United States can choose from lowing World War 11, we had consensus and consistency in our foreign policy. We lost them in the Vietnam agony, and we have failed since to rebuild them-despite the progress we thought we were making in the early years of the Reagan Administration.

At the same time, the world is becoming an increasingly confusing place. We have lost our postwar dominance; other economies are growing in power. The developing world is becoming more chaotic. Because of the world's increased interdependence, this chaos threatens the American national interest.

Structural Weakness

A coherent policy is made even more difficult by a fundamental change in the way this nation makes foreign policy decisions. When the Constitution was written, the only two entities of government which were considered to be involved in foreign policy were the President and the Senate. Because the chief executive and senators were Chosen indirectly by the Electoral College and the state legislatures, they were insulated somewhat from the vagaries of public opinion.

Now, both the President and the Senate are elected directly, and the House of Representatives, that most democratic of bodies, has become an integral player in the exercise of American foreign policy. The appropriations process has become a powerful policymaking tool, as money has become a far more vital ingredient of foreign policy than our founding fathers ever expected. The problem, of course, is that members of the House are always running for reelection; they do not have the luxury to stand above the clamor in their home district.

As a result, disagreements over domestic issues such as the budget deficit and defense spending tend to overflow into the foreign policy arena. In the face of a serious need to restructure the domestic economy, vested interest groups press for protection from what they perceive to be unfair competition from abroad. Unfortunately, protectionism cannot be confined to economic relationships with other countries. It spills over into the realms of international politics and security.

Repairing the System

In our effort to make our foreign policy more effective, we must first rule out any significant modification in our government's system of basic accountability. If asked to choose between democracy and effective foreign policy, at present at least, the great majority of Americans will choose democracy. That fundamental limit has to be accepted by those who are in charge of foreign policy. They have to realize that they cannot try to sustain policies against the overwhelming opposition of a majority of the American people.

The task is to improve our ability to execute foreign policy within the present structure of American democracy. We are not going to revert to aristocratic control. But neither should we accept a foreign policy in which public opinion rules supreme on a day-to-day basis. The public can set the limits of foreign policy, but it is singularly incapable of telling us what to do.

Instead, the federal government must learn to govern again. In recent years it has attempted to rule by presidential commission. We have had commissions on the Social Security Program, on strategic arms talks, on Latin America; their establishment is a sign of the inability of Congress and the executive to compromise effectively on complicated and difficult national issues. Before we can improve our performance in the rest of the world, we must work out our own domestic difficulties the budget deficit, the trade imbalances, and the structure of our own economy, in particular the industrial sector.

Next, we should choose not to pursue policies that are divorced from our own national principles. Marshall said that a great power cannot pursue one set of policies at home and another abroad. This does not mean we should give up covert action or secrecy forever. But both secrecy and covert action should be subjected to the basic two basic approaches in pursuit of its foreign policy. We can try to create and expand an international identity of interests and to reduce the extent to which our interests and our perceptions are in conflict with those of other countries. As a former diplomat, I would argue that this approach implies a process of negotiation, either formal or informal. Negotiation at the same time implies compromise, a quality with which most Americans are generally not very comfortable when it comes to dealing with the rest of the world.

The alternative to compromise is to deal with the world through coercion or the use of force. The two approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In fact, in the modern age one cannot negotiate without a certain element of force. We have had difficulty, particularly in the last few years, in blending those two seemingly different but mutually reinforcing approaches to our objective: to create that situation in the world which makes our domestic objectives feasible.

Taking Credit

Frequently, Americans do not understand that most of the world's geographic area and almost all of its population lie outside the jurisdiction of the United States. Our expectations about our ability to change the behavior of other countries are highly exaggerated; we fail to realize that major changes in the behavior of other countries come primarily from within those countries, and only marginally and incidentally as a result of external pressures that might be brought to bear on them.

One example is the Soviet Union's new policy of glasnost. We have been talking for years about the need for the Soviets to open up their system and society. Whether this opening is real or phoney, permanent or only transitory, remains to be seen. But it is a result not of U.S. pressures and moral hectoring but rather of a change in the perceptions of the Soviet leadership as to what is in its best long-term interest.

On the other hand, we must remember that we are a global power and that other countries in the world consider the position of the United States when they make their own national decisions. Therefore it is essential, if we are going to live in a coherent world, that other nations be able to predict to some degree where the United States is likely to stand on major issues. In U.S. foreign policy it is much more important to be consistent than to be 100-percent correct.

Need for Consensus

A consistent foreign policy is difficult for the United States because consistency requires a broad and stable consensus as to what our national purposes should be and what means are appropriate to the pursuit of those purposes. In the years immediately Folprinciples of accountability of our constitutional system. The buck not only does not stop below the President; it does not stop until appropriate congressional leaders are kept informed of administrative actions.

We must also avoid the romantic notion that covert action is a substitute for foreign policy. When we try to make it such, as I suspect we did with Nicaragua, covert action becomes a disaster. Secret acts can be, at times, a useful supplement to a foreign policy, but never a substitute for it.

On the other hand, we should not hesitate to pursue policies abroad that are direct projections of our own national values. The concepts of personal freedom, economic advance, and social justice are not the exclusive property of North America and western Europe. They have a universal appeal. We must be realistic and patient as we pursue those objectives abroad, but we as a nation have a direct interest in the democratization of other countries. Democratization increases the set of common interests that are the ultimate goal of American foreign policy. It is also a useful element in building our own national consensus without which foreign policy cannot succeed.

Consequences of Failure

I have a good deal of faith in the capacities of American democracy and in the good sense of the American people. But success in the world is far from certain. To rebuild national consensus on our international mission will be extremely difficult. It will require in the first instance a degree of compromise among ourselves. We must overcome the polarization between the non-majority left and the non-majority right and the inability to conduct a civil discourse that is evident in the press and the Congress.

If we fail to rebuild consensus, and if we cannot develop a clearer national notion of international purpose, then I believe that the United States will gradually fail as a global power. Our power and influence will diminish.

Many Americans would welcome that. They think our national life would become less complicated and less contentious. And it might, temporarily. But our withdrawal is likely over the longer term to lead to an even more untidy and tumultuous world. There is no other country or set of countries whose governing values are compatible with our own and who are prepared to take up any significant share of the global burden the United States might lay down.

It is not simply a question of passing on the baton to the next generation of global leaders. If we lay down the baton, in all likelihood no one is going to go near it.

That would mean, I fear, that at some later point, we might face an even harder choice. Remembering Marshall's dictum that the goal of American foreign policy is to preserve our national values as political realities, we might find that the values themselves are in grave danger. In the face of international chaos or threats from abroad, the American people just might choose the promise of efficiency and effectiveness over some of their fundamental freedoms, and that would be a tragic outcome.

For myself, I try to balance my inherent optimism with cautious realism. On the one hand, I recall a poem by Carl Sandberg in which a traveler in Egypt asks the Great Sphinx to share with him the distilled and essential wisdom of the ages. The sphinx looks down at the tired traveler and booms, "Don't expect too much."

Another, less cynical remark contains at least as much truth: "American life at all points, as in most societies, is becoming more democratic in that more people at least seem to have more say as to more things," one wise soul commented three decades ago. "As a general direction for a free and mature society," he added, "this seems to me both inevitable and right. I am also sure, however, that this development has within it the seed of its own undoing unless it is accompanied by corresponding growth in the same community's resourcefulness in reconciling independence, answerability and the dilemmas of leadership within the democratic process."

Those words are from a convocation address given at this College during my first period of residence here in 1958. The author was John Sloan Dickey. Both the optimism and the warning, I think, are still valid today.

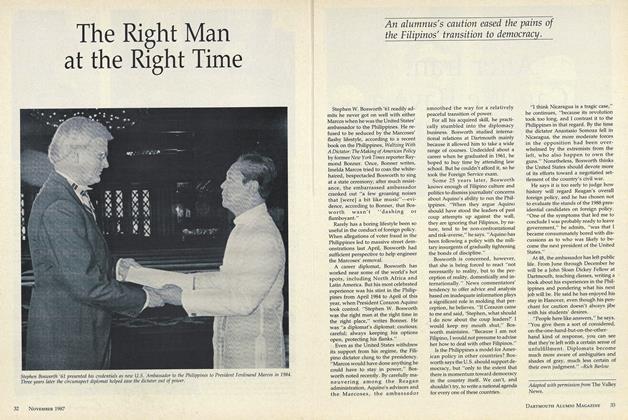

"We have lost our postwar dominance" of the economic world, says Bosworth. Theformer ambassador is now teaching at Dartmouth as a Montgomery Fellow.

Oliver North's Iran-Contra argument, that American effectiveness abroad requires secrecy, is not a new one.

The ambassador with Cardinal Sin, the Philippines' top prelate. Bosworth believes weshould project national values-including democracy-abroad.

In U.S. foreign policy it ismuch more important tobe consistent than to be100-percent correct.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

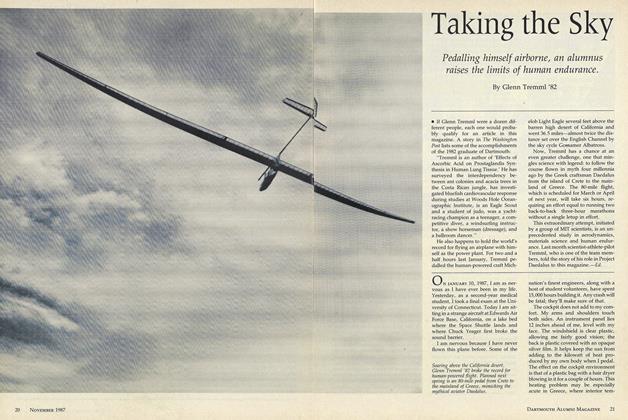

FeatureTaking the Sky

November 1987 By Glenn Tremml '82 -

Feature

FeatureAre Conservatives Being Silenced?

November 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureRooming with Style

November 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

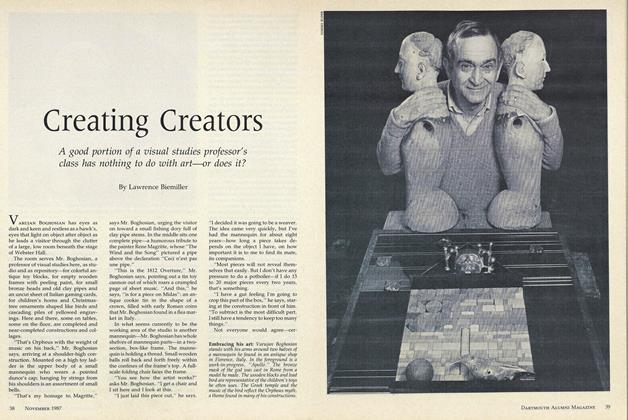

FeatureCreating Creators

November 1987 By Lawrence Biemiller -

Feature

FeatureThe Right Man at the Right Time

November 1987 -

Feature

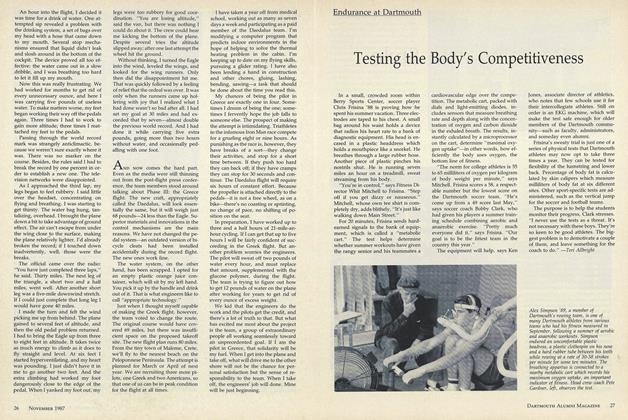

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

November 1987 By Teri Allbright

Features

-

Cover Story

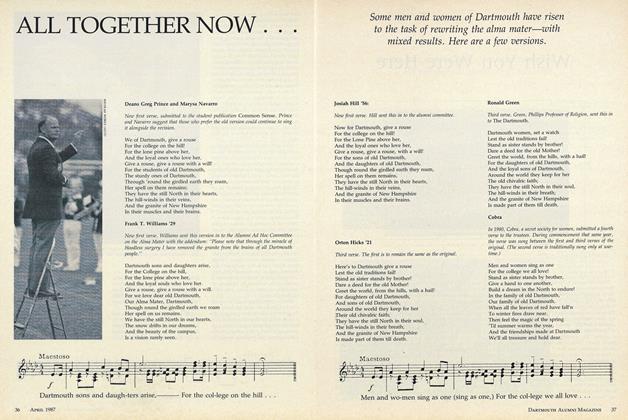

Cover StoryALL TOGETHER NOW ...

APRIL • 1987 -

Feature

FeatureTHE SPIN DOCTRINE

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2013 By JAMES KEGLEY -

Feature

FeatureThe 50-Year Address

July 1961 By KENNETH F. CLARK '11 -

Feature

FeatureMen in Uniform

Sep - Oct By LEE MICHAELIDES