The issue is not why bad things happen to good people, but when.

oUR SECOND child took much longer to conceive than had our daughter Bria, born two years earlier. It may have been because we wanted another baby so badly that it seemed less spontaneous. When we succeeded, we were delighted. Still, I was ambivalent about having a second child, fearing the loss of more independence just as strongly as I yearned for a male heir.

In one sense my wife, Susy, was not superstitious about the new baby. She decorated the nursery, while some of our friends who were pregnant did very little until the last moment. We prepared Bria by finally weaning her and ceremoniously moving her from her crib to a real bed.

I was quick to dismiss Susy's premonitions of giving birth to a headless child. In spite of my age, 40, and family history (my mother had lost two children to birth defects), I believed there were no reasons for either of us to fear an abnormality in our own child.

Bria and I read and reread a bedtime story called "Michael," which recounts how a family anticipates a new baby and the impact of the birth on the older child. This tale helped both Bria and me deal with the upcoming birth. Her matter-of-fact response and coy laugh relieved me.

As the pregnancy progressed, Susy appeared to have no complications beyond morning sickness and a 40- pound weight gain. She maintained her role as wife and mother admirably. By the third trimester she tired easily, and I pitched in as best I could, continuing my private medical practice by day and becoming assistant cook and housekeeper by night.

I wanted to wait for the finished product before choosing a name but Susy enthusiastically suggested one after another. We finally decided on Jacob Emanuel, after my grandfather, or Talia Nicole for a girl.

At our eighth-month visit to the doctor, we learned that our baby was in the full breech position. We chose not to try the more risky "version" procedure, in which the doctor manually turns the baby in the uterus, opting instead for a Caesarian section. This choice eliminated the need for an ultrasound, which helps locate the placenta and also can detect fetal abnormalities.

The anxious night before the scheduled Caesarian section passed much too quickly. We drove silently to the hospital.

I took pictures while the staff readied Susy for surgery. Our family practitioner and I donned our scrubs and made small talk. Susy was awake in the brightly lit operating room as her epidural took effect.

Moments after the incision, Susy's blood pressure plummeted ominously. My heart stopped for what seemed like ten minutes. The drop was due to the excessive pressure of the baby on the vena cava, the main conduit of blood returning to the heart. Our anesthesiologist quickly corrected the problem by increasing the intravenous-feeding fluids. I stood by, squeezing Susy's hand.

Suddenly, quiet replaced the usual delivery room banter. Fear gripped me as I heard our physician say, "Someone get the newborn intensive care doctor right away." I presumed the doctor was concerned that Susy's temporarily low blood pressure might have put the baby in distress. But that wasn't the case.

Our physician came to the head of the operating table and said, "There's been a problem. Your baby has an underdeveloped brain." I later learned that in this condition, hydranencephaly, the entire forebrain or telencephalon is absent because of a firsttrimester neural-tube closure defect, and this leads to death.

Neither Susy nor I could watch as the anesthesiologist gave Jacob a few pumps of oxygen. Neither of us wanted to see him. I feared how the baby might look and worried about how Susy might react to his distorted features. We knew without speaking that we did not want to prolong his life if his condition was fatal. I was concerned that recent Baby Doe decisions might allow medical technology to sustain Jacob with a condition incompatible with life. As we held each other, they took him to the neonatal intensive care unit.

After I left Susy, I met our obstetrician in the hall. She was crying. I didn't cry then, feeling a need to be strong in case I had to make any decisions. Susy and I felt as if someone had lied to us. We were failures, foolish to anticipate such joy.

Susy asked me to call a close friend, Debbie, who was pregnant. Overcoming their own fears and sadness, she and her husband were quickly at our side. Usually squeamish about medical matters, Jim summoned his bravado and together we went to talk to the doctors. My fears of a technology which could delay Jacob's natural death were heightened when a second neonatologist offered to catheterize Jacob and monitor his renal functions. I became angry, but Jim calmed me and explained again to the doctor that we wanted nothing done to keep Jacob alive.

Jim and I drove silently to Bria's play group. I told Susy's mother, who had come to take care of Bria, what had happened. Bria played happily and hardly seemed interested in the outcome of the delivery. She seemed least equipped of us all to understand the loss. I knew I should explain death to her honestly and in terms she could understand. I thought I might undermine her trust by not telling her Jacob was gone. Would she subsequently connect a trivial illness or separation from a loved one with the loss of Jacob?

Another friend, Kristie, visited us and told us about her sister, whose child had been born with trisomy 21, a chromosomal abnormality that leads to death. Her sister and husband had at first refused to see their child. Eventually they took the baby girl home and held her in their arms when she died two weeks later.

Kristie challenged our reluctance to see Jacob. But I argued that he might be a monster or that by seeing him I would become more attached and suffer an even greater loss when he died. "See Jacob for me," I begged her. "I can't."

A resident on call helped: "I may sound like an amateur psychologist," he began. "I think you can handle it. It will be better for you later if you see him and try to accept his birth."

Finally, I found myself approaching the warm incubator in a separate section of the intensive care unit where Jacob lay. His body was so much like Bria's, perfectly formed. His eyes were prominent and opaque. Above his eyebrows was a flat and purple lumpy discoloration shaped like a skullcap. I was overwhelmed with an intense tenderness for him.

As I rocked him in my arms, I moistened "his mouth with a wet piece of gauze. He was so fragile. After placing him back in a nurse's arms, I went to ask Susy if she, too, would be willing to hold Jacob. Since the delivery she had lain quiet, numb and dry-eyed. She agreed to meet her baby.

The nurse brought Jacob to us. It was only then that we could name him, accept him as our own and offer this tribute to my grandfather. Susy took Jacob into her arms and cradled him. Tears began to well up in her eyes and she cried for the first time since the birth. She would later wish she could have held him longer, somehow prolonging his life or relieving any pain she imagined he felt.

In the middle of the second night, a nurse told Susy that Jacob had died. The woman gave the news and left quickly (we-later learned that it was her first night on duty). Susy was stunned. As I struggled with the necessity of disposing of his small body, I felt very alone. We decided to have him cremated and planned to spread his ashes once the ground had thawed so the life and growth of summer would accept him.

For the rest of our hospital stay, we were strange interlopers on the maternity ward among happy women with healthy babies. One father approached me tentatively: "I wish there was some way my baby could be yours." I hugged him, comforted by such compassion. Our physician had given us the book "Empty Arms" about infant and pregnancy loss.

In spite of all the support we were offered, we still returned home feeling empty. We felt that other, less deserving people had gotten more than they deserved, while we had gotten far less than we deserved. A friend reminded me that the saying is not "why" bad things happen to good people but "when."

At home, Susy cried often and could not tolerate complaints other parents had about how much work a second child could be. To her they seemed ungrateful. For my own depression I eventually sought professional counseling.

Susy and I told Bria that Jacob was very ill and could not come home. Later, we told her her brother had died. At first she seemed puzzled by the idea of death but then surprised us by matter-of-factly explaining he had "gone to heaven."

We had a kaddish, a service usually held for the dead, which according to strict Jewish law meant anyone who had lived longer than 30 days. The ceremony was attended by friends and family as well as Jacob's doctors and nurses. Instead of just a prayer for the dead, the kaddish became an affirmation of the love Susy and I had for each other as well as for all the people in our lives during these difficult times.

Friends and hospital staff had ignored Jacob's imperfections and shown us how to accept him lovingly. They helped us accept his birth so we could appreciate the sadness of his death. But we still felt that we had failed or that we had done something wrong to produce this defect. We bickered more than usual, while I struggled with Susy's depression and she kept asking why I seemed to show so little emotion about Jacob. She lost interest in maintaining our home in the usual order.

Gradually, though, she found solace in the flute (she is a professional flutist). She also benefited by mingling with her friends at Bria's play school or by running errands. Talking constantly about our feelings relieved Susy's depression and helped me break through my shell. This would be an important vehicle for the success of our marriage.

Initially, Bria played quietly alone. She sensed our sadness and felt her own. She started wetting her pants again and picked at her food. Although I searched for a book to read her about death, the best one I found was about the death of a cat. I feared Bria might associate Jacob's illness and death with a loved one's sickness or absence. We also worried that Bria might expect to die if she ever became sick or might regard a short trip as a permanent separation from us.

But these fears never surfaced. Bria definitely required more attention at bedtime and became more afraid of the dark. She was routinely in our bed when I awakened in the morning. We simply offered as much security as she required, becoming less indulgent as she became more comfortable and stopped bed wetting and her distracted play.

Months later, it was Bria who gave us hope for the future. After asking her usual painful questions about Jacob, she tilted her head back and smiled at Susy: "Oh well," she said. "You and Daddy will make another baby, won't you?"

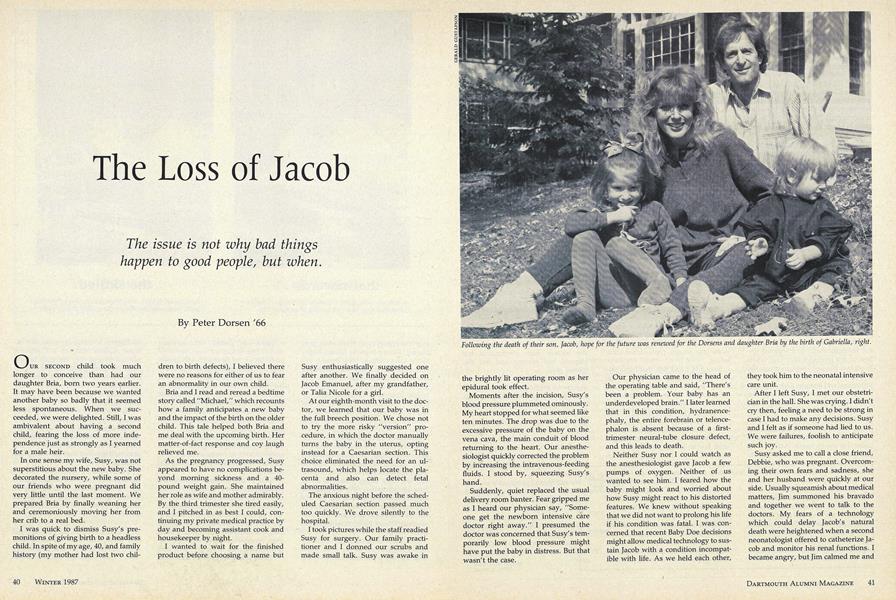

We did. Gabriella Nicole is now 17 months old. Our overprotectiveness hasn't kept her from losing two teeth or from getting three cuts big enough to require stitches.

We still remind people that we have had three children but that Jacob died. We are sad he died but proud we knew him even if it was for a very short time.

Following the death of their son, Jacob, hope for the future was renewed for the Dorsens and daughter Bria by the birth of Gabriella, right.

Peter J. Dorsen '66 is an internist in privatepractice and a freelance writer. This articleis adapted with permission from the Minneapolis Star and Tribune Sunday magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

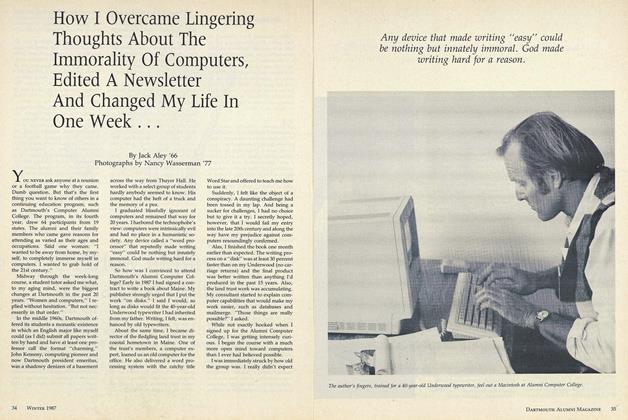

FeatureHow I Overcame Lingering Thoughts About The Immorality Of Computers, Edited A Newsletter And Changed My Life In One Week ...

Winter 1987 By Jack Aley '66 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIf I Could Do It Over

Winter 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

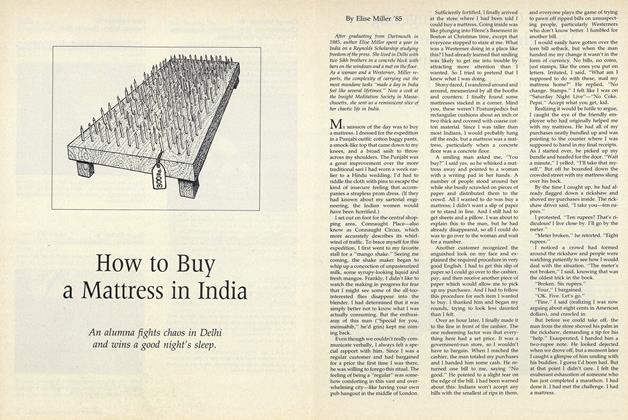

FeatureHow to Buy a Mattress in India

Winter 1987 By Elise Miller '85 -

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

Winter 1987 -

Feature

Feature4. Men and Women

Winter 1987 -

Feature

Feature2. Drinking

Winter 1987

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCarole Berger Professor of English 2 wolves in a single run

January 1975 -

Feature

FeatureSix Questions for the Candidates

APRIL 1989 -

Cover Story

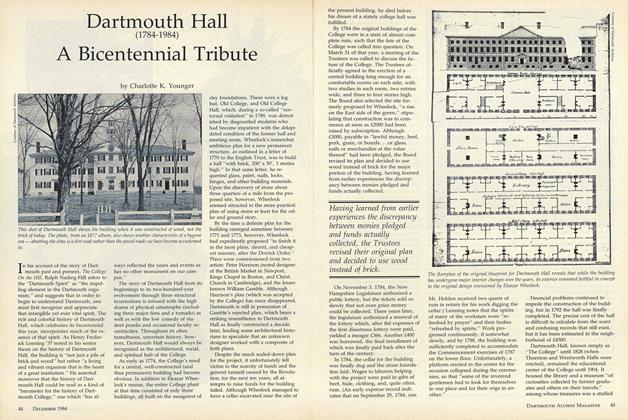

Cover StoryDartmouth Hall (1784-1984) A Bicentennial Tribute

DECEMBER 1984 By Charlotte K. Younger -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Feature

FeatureSteady State

September 1976 By Pierre Kirch -

Feature

FeatureOliver Wendell Holmes Slept – and Taught – Here

May 1956 By ROBERT S. BLUM '55

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow I Overcame Lingering Thoughts About The Immorality Of Computers, Edited A Newsletter And Changed My Life In One Week ...

Winter 1987 By Jack Aley '66 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIf I Could Do It Over

Winter 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

FeatureHow to Buy a Mattress in India

Winter 1987 By Elise Miller '85