Second Chances It is ultimately mysterious, this business of learning and growing. One thing is certain: we change each other.

MORE THAN Anything else, it is the smells that bring me back: the smells of chalk dust and wax polished floors, of holy water and bologna sandwiches. For a moment I imagine that I am seven years old again, mulling over two perennial preoccupations: Do nuns have anything on underneath? and, If a nun wore a headpiece long enough, would her brain crease right in half? But then the door shuts behind me, and 18 real seven year olds stare back. Oh hell, I think: what am I supposed to do now?

Ten years ago I would never have believed I'd be back—not to an elementary school, and least of all to a Catholic one. When my mother had decided to pull me out of parochial school after the sixth grade, at the urging of one of my teachers, the principal had told my mother in no uncertain terms that she would burn in hell. I think my good Catholic mother must have been shaken to the core, but she didn't relent. And I, for my part, had hardly ever looked back.

Until now, that is. Few decisions represent radical departures, however much they may appear so from the outside; most are rather accretions, pebbles slowly piling up that one day redirect a tide. And so it had been with my decision to try teaching.

I'd left a challenging position in the private sector a few years earlier because of what I have come to call the "shower test": i.e., that what you think about when you don't have to be thinking about anything is a pretty good indicator of where your true interests lie. I had also been doing so much volunteer work in education that, practically speaking, I might as well have been in the field. But my next position as executive assistant to one of the deputy heads of the New York City public school system didn't end up providing the direct involvement that I craved.

One incident from my last six months at the Board of Education stands out in my mind. I had been working for what seemed like ages on an innovative program designed to train aspiring principals. My responsibilities had been to coordinate the development of the program budget and contract, and to oversee the renovation of part of an old school building for use by program participants. As is frequently the case in large bureaucracies, cracies, what sounded relatively straightforward proved not to be: more hands do not always make for lighter work.

But then one day the pieces were all more or less in place, and the first class of principals to be had been invited in to inspect their new training site. I remember standing enviously aside as they milled around. I felt as if I'd missed the boat. The program head was asking if I'd be willing to give participants a talk on how to negotiate one's way through a bureaucratic maze. She wanted me to help train them, but I wanted to be them. I think I realized then that I was going to leave—it was only a question of when and for where.

One colleague's reaction to my resignation was telling. Poking his head into a crowded elevator, he shouted, "What the hell are you doing? Don't you know how dangerous teaching is these days? This could end up spoiling your educational vision!"

Indeed. For one of the ironies of working in a high-level administrative position without ever having provided the services that one is making policy recommendations about is that the realities of implementation don't impinge as keenly on one's sense of possibilities. Sometimes that's for the best: dirt under the fingernails can, unfortunately, keep one from looking up and out. But bold action is not always wise action. And I was becoming more curious, about which of my pet theories were just that warm, fuzzy, and trained to do what I wanted and which had lives of their own, lives that were reflective of something outside themselves. I didn't want to become like the prototypical PTA protester who stands up at a meeting and announces that he or she "knows all about education" byvirtue of having attended school. (Yes, I always want to say to people like that, and I know how to use Drano, but don't call me when you have a flood.)

First, the philosophical:I had been happy in the second grade. "Effective first and second-grade teachers are usually cases of arrested development," a colleague at the Board of Education had advised me. I thought that sounded about right. I also felt there was more of a chance to have an impact in the lower grades, though I didn't suspect at that point just how deeply reciprocal that influence would be. As for the practical, I was pretty sure that I couldn't handle people who spent much of their time engaged in either (a) throwing up or (b) wetting their pants. I had done my share of both in my day, and the reaction of the nuns had left me with an unmitigated sense of dread. This, I thought, pretty much ruled out teaching kindergarten or first grade, which were the other available options.

Still, looking out at my class on the first day of school I felt more nervous than I had in any other new job. Mostly, I think, it was the lack of any visible support system. When in doubt on other new assignments, I'd simply asked questions, lots of them, or observed bosses and peers to figure ure out what was expected. But here, despite the professed (and I was to find out later, genuine) willingness of my colleagues to offer what assistance they could, the opening bell still rang and it was me and, well, them.

"Them," of course, took all of about ten minutes to assess the situation, and proceeded to raise mayhem. Children in the closets. Children under the worktable. Children in the bathroom. Children on my nerves. "Be very clear with them from the start," a colleague had advised, so we had started out the day with three rules: (1) We take turns speaking; (2) we keep our hands to ourselves; and (3) we share. As the hours rolled by, however, I found myself mentally adding such other items as: We don't tattle. We don't pick Miss Cleary's plants. We don't draw on the floor. We don't scream. We finish pulling up our trousers before we come back from the bathroom. We don't burp in each other's faces. And so on. I was shattered: so much for romanticizing children.

But the second day is better. My eyes begin to adjust to the light, as it were, my ears to the din, and faces and names gradually couple. Genderwise, the group is almost evenly divided: ten boys, eight girls. Six children are Hispanic, two are Indian, one is black, and the rest are a mix (mostly of Irish and Italian descent). As a group, they are young; fully one-third of them won't turn seven until the end of the calendar year. Most are lower middleclass; two are from families receiving public assistance. Eight of the children come from single-parent homes.

Perhaps more importantly, all are very much themselves. One tends to think of children as so malleable, and perhaps at the margin they are. But they are also quite well formed at this stage by the accidents of birth and family and circumstance, by forces not readily controlled by a teacher. No doubt this is sometimes for the best, as at least one of the kids seems to grasp instinctively when he demands, "Are you a good witch or a bad witch?" But good, bad, or indifferent, I soon begin to see the limitations of my bag of tricks.

Curious about their images of self and others, on the second day I hand out blank ovals and crayons and ask each child to draw the face of his or her guardian angel. In blues and blacks and yellows, in squiggles and broken lines, their stories begin to unfold. The results are arresting, and none more so than Renee's. "This is really nice, Renee," I say as I tape her picture to the wall. "But what are these little dashes all over your angel's face?" "Knife marks," she says without blinking. I later learn that Renee is being raised by her maternal grandmother in a pretty rough local housing project. Her father is in prison; her mother, a recovering drug addict, lives nearby but not with Renee. I can only guess at what this little girl has seen in her seven years.

By virtue of their rather poor performance on the prior year's standardized tests, fully threequarters of my class have been assigned to remedial reading, and a few to remedial math as well. In theory this sounds like a good idea: a federally funded remedial teacher will provide extra help for those who need it most. But in practice it is a logistical nightmare. For starters, the kids can't be taught inside the building since that would be considered a violation of the separation of church and state. Instead they have to go out to a trailer that is parked behind the school. They also have to be taught in very small groups and for short periods. What this means, in effect, is that for the first two hours of our day, four hours a week, we have a kind of musical chairs going on in which a group of three to six children goes out and comes back, followed by the next group, and so on.

Since I also happen to be teaching new material during this period because that is when they are freshest and most focusedwhat looks on paper like supplementary instruction in fact ends up being replacement instruction. I find that I have to scramble all year to ensure that kids make up the work that they have missed while out in the trailer. Now this is a program conceived by a bureaucrat, I think to myself: the monies could be much better spent on something like an afterschool tutoring program that would complement, rather than conflict with, the learning going on in the regular classroom.

Most of the parents of my students are despite the hardships of some of their individual circumstances genuinely interested in helping their kids. But many of them feel they don't know how. And some of them, as I come to realize, also don't have very high expectations for what schooling can or will do for their kids. More solidly middle-class parents tend to expect a return on their investment of tax dollars or tuition and if that expectation fails to be met, then the schools hear about it. But not so with many of these families.

About two months into the school year I start sending each child home at the end of the week with a folder containing a short progress report, work done during the week, and worksheets or other assignments in those areas where a given child needs more practice. This is very popular with the parents. It is not popular with the kids. "Hey, Miss Cleary," says Hector one day after looking rather disgustedly at his assignments for the weekend. "Like this isn't high school, you know. We're just little kids."

It isn't something they let me forget easily, in spite of my greed for all that I want them to learn. My early attempts at behavior modification, for example, had been more or less a complete flop. I had created an elaborate "Stars Chart" as a behavioral incentive, only to find that what I seemed to have conditioned them to do most consistently and successfully was to nag me about marking the damn chart. As I reluctantly conceded to a friend, "I'm afraid I think that whatever it was Skinner did with rats works better with rats."

So rather than have them attempt such seemingly Herculean feats of will as staying in their seats, over time I figured out that it was more effective to turn much of what we did into games. We played Bible Baseball, Sight Word Football, Phonics Bingo, Science Tic Tac Toe. We had a Math Casino, where students raced in teams to figure out the sum/difference of the dots on three or four rolled dice (6+42+s=?). We played a version of Simon Says, where students had to read the instructions off a placard (e.g., Hop three times on your right foot, turn around to the left, and say "Hoya!"). It was loud and messy and often didn't go as planned. But it was often hilariously funny as well and, on days when I thought I might go out of my mind, I would take comfort from the plain but eloquent sign on the third-grade teacher's door. It said simply: Under Constrction.

Shortly after Thanksgiving the principal announces that she "would like" our production for the Christmas show to be in French. I would not like. But I don't really have a choice. One of the things I am learning is that, among other functions, schools are public-relations machines, especially when they happen to rely on tuition for their survival.And French, which I have been teaching them in small doses since September,looks good.

So I translate "The Twelve Days of Christmas," only to find that they have enough trouble doing it in English, much less in French. We settle on an improvised translation of "Silent Night," plus a rendition of the months that is part chorus-line, part cheerleading routine. Two days before the show, however, the music teacher goes into the hospital, leaving the principal to serve as accompanist. The kids can't hear her introductions and figure out when to come in, partly because she keeps changing them. I expect disaster.

On the night of the show I am tying haloes (glitter covered paper plates) to the girls' heads and taping French-style moustaches to the boys' upper lips. The boys are so nervous that they keep sweating them off. Finally they are onstage. I can't believe it: they bring the house down. They even kick in unison, even though in rehearsal they had mostly kicked each other. "We wanted you to be happy," one of them says afterwards. I am too choked up to respond.

But the euphoria does not last long. Throughout January I continue to fret about Rosa. Rosa is a full year older than her classmates, having lost some time when she transferred from a public school in New York City. Her piercing questions delight me and are, invariably, levels above those of the other children. "If dinosaurs lived so long ago," she demands one day, "how are you so sure that those are their names?" Or: "How do you know that your color red is the same as my color red?" Or again: "If God is so good, then why did He make drug dealers?"

In the free association world of a seven year old mind, everything is connected to everything else. And just about anything reminds poor Joseph of his cat. Originally, their refusal to compartmentalize their thinking had frustrated me, because it made it much more difficult to keep discussions on track. But eventually I had relaxed, mostly because I had come to realize that the most interesting vistas frequently emerge through the side windows.

This particular thought-train had begun with a suggestion by Dinamarie that Cinderella probably had a baby and got divorced. Which reminded Angel of our recent visit to the pediatric ward at the local hospital, which reminded Shireen of the time she (accidentally) bit the dentist, which reminded Carmen of Bart Simpson, which reminded Joseph of his cat. For which offense Rosa, for added emphasis, had heaved one of the "crayon orphanages" (empty coffee cans in which we stored the übiquitous stray crayons) in Joseph's direction.

Now, as Rosa sullenly moves toward the door, Dinamarie announces to the class, "Looks like Rosa is in deep spinach." Dinamarie, a lovable child who cannot seem to concentrate on phonics for more than five minutes at a time, nonetheless does a superlative job as the class busybody. "WDIN" is how I affectionately refer to her among my colleagues: "all the news, all the time." Now I glare at her. "I will keep my business to myself," she says sheepishly.

Rosa is standing outside the door, head down, furiously chewing on her fingers. I crouch down, take her hands in mine, and tilt her chin up. Her eyes have filled with tears. "Look, Rosa," I say softly, "I know you have an awful lot of big feelings. But you're safe here. And other people have feelings, too. You can't just go walking all over them like that. How would you feel if Joseph said something like that to you?" "I could care less what Joseph thinks of me," she replies defiantly. We talk for a few more minutes. The sound of shrieks from inside the room grows louder. Rosa hugs me and rather grudgingly apologizes to Joseph. But later in the day she gets into a pinching and hair-pulling tussle with Shauna.

I feel as if I am getting to know Rosa's stepmother quite well. That afternoon, I suggest to her again that she take Rosa in for counseling. We have had variations of this discussion many times before.

point of view, Rosa has improved.

I sympathize with the stepmother, at the same time that I am baffled and frustrated by what seems to me like her passivity in the face of the child's anger and pain. I wonder if I am oversensitive, or meddling. Still in her twenties, the stepmother is seven months pregnant and is working fulltime as a clerk at a local discount outlet. She obviously cares very deeply for Rosa, but the strain of dealing with the child is showing.

And I'm sure my constant questioning doesn't help. No, she doesn't know exactly what happened—Rosa has described "terrible things," but the stepfather (the apparent perpetrator) has denied everything. No, they never took him to court, because they weren't sure whether Rosa was exaggerating. Yes, Rosa still has crying fits and outbursts at home. No, she and her husband don't think that counseling is the answer; they would prefer to "give it a little more time." Yes, they still allow the mother and stepfather to take Rosa for an occasional weekend. It goes on and on. And it goes nowhere.

Then one day the dam bursts. I walk into the school cafeteria, which doubles as a gym, to retrieve my class. The gym teacher, whom Rosa likes, has been working with them on handstands, and I watch from the sidelines as he pulls Rosa up by her ankles and tells her to straighten her arms. Suddenly she becomes hysterical. "Let me down!" she screams. "Stop, stop, please stop!" I run over to grab her and hold her in my arms. "What is it?" I say."My step stepfather used to hang me, hang me up, upside down with ropes," she chokes out between sobs. I think I am going to throw up.

But one day Samson had gotten out of his cage, and my father his alcoholism by then in full swing had, in a drunken fury, gone after Samson with a broom, breaking his wing. For years afterward my dreams had been filled with birds, and images of flight.

But now I am filled with rage, at the cruelty and ineptitude that is visited on children. It is ironic, I think to myself bitterly, that people think least of hurting those who are capable of remembering it most. It is as if they rationalize that because children's bodies are small, their feelings must be too, or (worse) that children will outgrow nasty memories much as they outgrow unfavored clothes. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Partly, I think, children's memories are so deep because their sense of time is fundamentally different from that of adults. As anyone who has ever lived or worked with young children can attest, "now" is all there is. And if now happens to be hell, then hell can last for a very long time.

Children's minds are also less cluttered than our own. I was constantly being surprised, in class, by their ability to supply the details of incidents that I remembered mostly in outline. What lodges in children's minds seems to stand out more, as if in relief, and a single frame in time can retain a crystalline clarity for months or even years to come.

The next few weeks are harried. The principal has insisted that Rosa receive counseling as a condition of remaining in the school, and her father and stepmother have agreed. A psychologist from the local public schools has been called in to evaluate Rosa and to make a referral, but before he can get to her she takes a pair of scissors with her to the lunchroom and starts to saw on her wrists, saying she wants to kill herself. She is eight years old.

I am out with the flu on that day but, when I return the next morning, the principal calls me into her office. The psychologist has cancelled his other appointments and is on his way. When I see him tough, grim-faced, but with kindly lines etched into his face I wonder how he manages. He spends several hours alternating between Rosa, her stepmother, and me. "This child isn't likely to kill herself," he says finally. "She knows she's got some good stuff going for her now. But she's going to need some pretty intensive long term work. Just keep doing whatever you're doing and remember never to back her into a corner. You always gotta give a kid like this some options."

The results, edited for spelling, are straight to the point. "Dear President Bush," writes Carmen, "I know that World War 1 and World War 2 were bad and I hope that this won't be World War 3. My Dad is a Marine (reservist) and I hope he stays home because my mother is not in the picture..." Rocco writes, "Dear Mr. George Washington. I wish you were here because you were the best warrior. But that doesn't mean you were not wise. I am so worried about this war. I feel bad for the kids in the Middle East..."My favorite, however, is a little gem that reads, "Dear George Washington, I see you on the dollar bill and you are my favorite president, even if you had wooden teeth and never smiled. The war would be short if you were here but you died. I hope children in Iraq don't get killed. Happy birthday this month from your friend."

Almost before I know it, the end of the school year is approaching. The results of their standardized tests arrive and the lure of the quantifiable being what it is I am eager to have a look. I am also curious because I have been becoming aware of a sort of Lake Wobegon complex in myself: a conviction that people I find this interesting must all be above average.

Walking home later in the day with a sheaf of statistical analyses under my arm, I reflect that,try as we will to size it up or pin it down, it is ultimately mysterious, this business of learning and growing. Even when there is agreement on what is or should be the product (which is not often), it remains impossible to separate out the relative influences of, or even for that matter clearly to distinguish, the reactants in this explosive process.One thing, perhaps one thing only, is certain: we change each other. Hopefully, for the better.

Throughout the year the kids have been obsessed with the Ninja Turtle characters Donatello, Michelangelo, and Raphael so, near the end, I decide to show them some works by the artists for which the characters were named. Peter is looking at a reproduction of Michelangelo's "Last Judgement." "What a lot of fat people in Pampers!" he exclaims.

"What's an art critter?"

"Critic. It's someone who, when you look at a painting, tells you what you're supposed to see."

He thinks about this for a moment. "Why can't you just see for yourself?"

It is my turn to think. "Well," I say finally, "children can.But sometimes when people grow up they stop looking, stop seeing."

"Oh," he says, and then: "So I guess kids are better, huh?"

"Magic,"I reply. And I reflect: they are like magic. Something like magic. Something like a second chance.

All of this has made a tremendous impression on Peter. "Hey Carmen," he hollers across the room. "I saw the fat people first!"

Kiely and a "real seven-year-old.''

In their free-association world, all is connected.

IT IS IRO NIC, I think to myselfbitterly; that people think least, ofhurting those who are capable ofremembering it most. It is as if theyrationalize that because children's bodiesare small, their feelings must be too.

Dartmouth's first female RhodesScholar, Mary Cleary Kiely isa former assistant vice president of theContinental Corporation. She nowteaches at Our Lady of Grace School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFishing The River For A Monument

September 1992 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

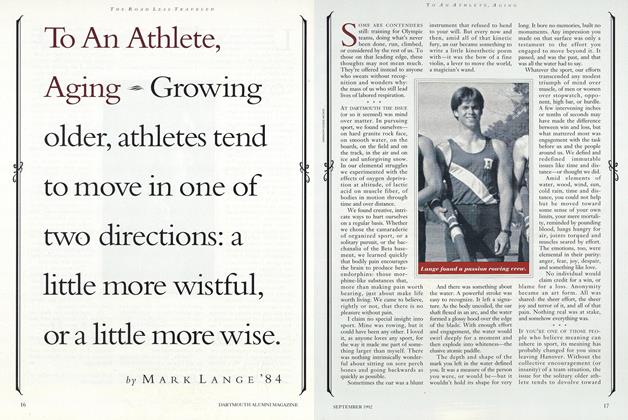

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84 -

Feature

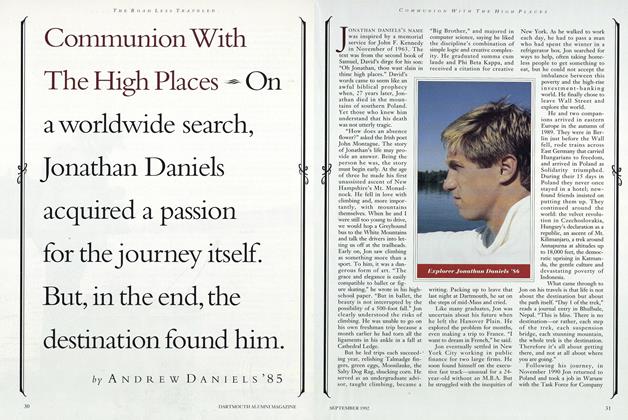

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDEATH and DYING

September 1992 By Professor Sergei Kan

Mary Cleary Kiely '79

Features

-

Feature

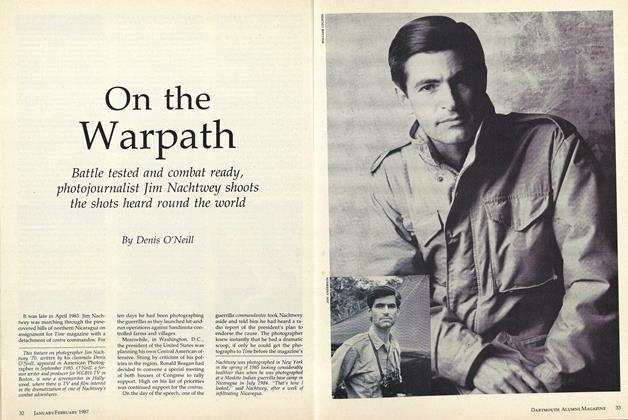

FeatureOn the Warpath

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Denis O'Neill -

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

FeatureA Look Backward and A Look Ahead

JULY 1964 By MICHAEL JAY LANDAY '64 -

Feature

FeatureOISER: Massaging the Media

May 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1962

July 1962 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

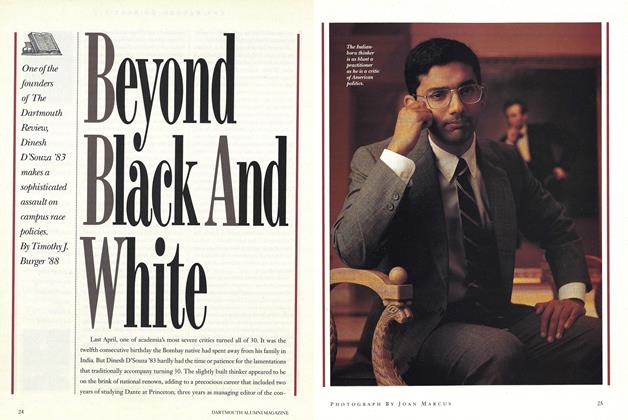

FeatureBeyond Black And White

JUNE 1991 By Timothy J. Burger '88