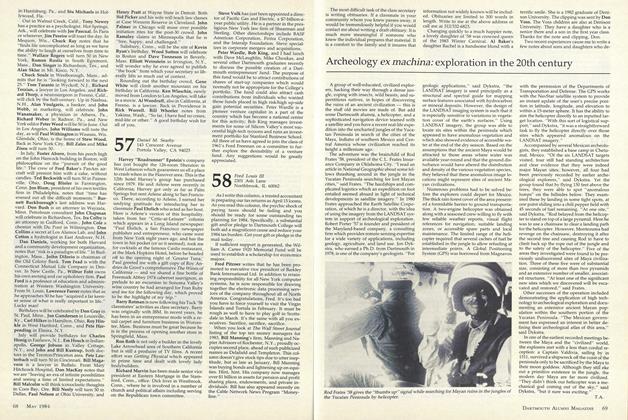

"I knew it was a hot item"

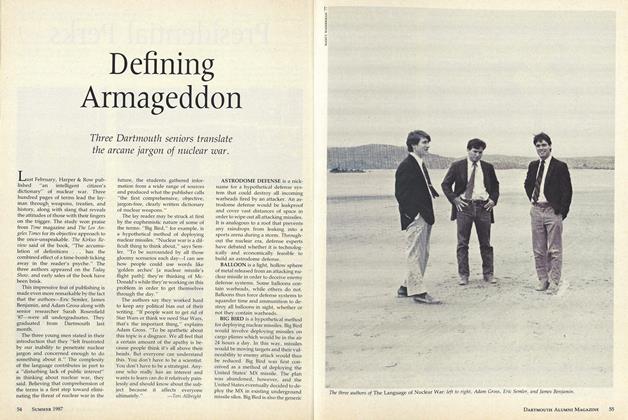

The young authors of The Language of Nuclear War dedicated the book to "our parents, who are probably as shocked as we are." Shocked by the prospect of nuclear apocalypse? "No, shocked that we actually wrote a book," grins Eric Semler.

Not that such an effort is unusual for him. A Russian and history major, he conducted research on arms control for two years as his senior fellowship. He spent his sophomore summer in Geneva as an intern at the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research; he was at Bit burg when President Reagan made his controversial visit to the cemetery there; and in the summer of 1986 he was a member of the U.S. delegation to the Arms Control Conference in Stockholm.

But it was in Baker Library that Semler first discovered the need for a dictionary of nuclear war terms. While reading a newspaper article in the periodicals room he found himself baffled by some nuclear jargon; surprisingly, no book existed to explain it. That summer, during his internship in Geneva, he began compiling nuclear war terms. He returned to Dartmouth with a list of 2,500 words. "I knew it was a hot item and if I didn't do it, someone else would do it soon," he explains.

He turned to three classmates James Benjamin, Adam Gross, and Sarah Rosenfield—who knew "even less than I did" about nuclear war. Funds from the Dickey Endowment, the Mellon Foundation, and the

Tucker Foundation provided the group with a Macintosh computer and some living expenses; the Dartmouth Ski School gave them an office to use. With the music of Elvis Costello blaring in the background, the four devoted most of the fall of their junior year to the book.

Like Semler, James Benjamin took a term off from classes for the project. While they all worked on every aspect of the book, his major contribution was the format they used. "I was the 'science guy', so I got to do more of the technical terms," says Benjamin. "I catalogued most of the weaponry, for example." A government major, Benjamin had studied East-West relations at Karl Marx University in Budapest, Hungary.

Adam Gross juggled two courses while working on the project. "I loved doing the book; my schoolwork seemed like a real hassle at the time," he says. He admits to having been the skeptic in the group; his father and his sister are in publishing, and he knows how hard it is to complete a book, much less get it published. "I'm really glad I was proven wrong," says Gross.

Since graduation, Semler has moved to Dallas to be a television correspondent for the College Satellite Network. Benjamin will attend law school at the University of Virginia this fall. And Gross has joined LEK, an international strategic consulting firm.

One thing they still have in common: each would like to write another book someday.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

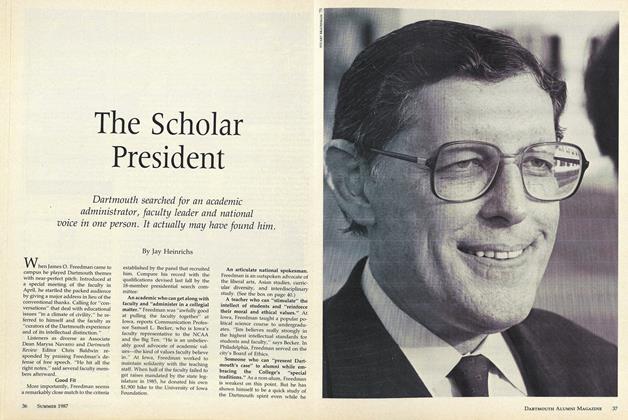

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

FeatureDefining Armageddon

June 1987 -

Feature

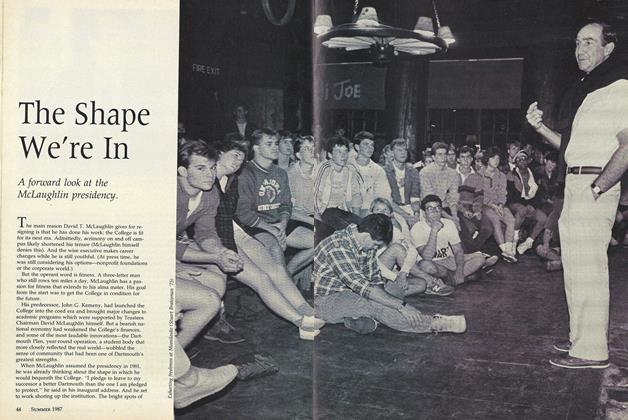

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Feature

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987

T.A.

Article

-

Article

ArticleTUCK SCHOOL CLEARING HOUSE ELECTS NEW OFFICERS

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleMovies Released

February 1934 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleStaff Appointments

MAY 1964 -

Article

ArticleTHE TRANSFORMING POWER OF LANGUAGE

SEPTEMBER 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott