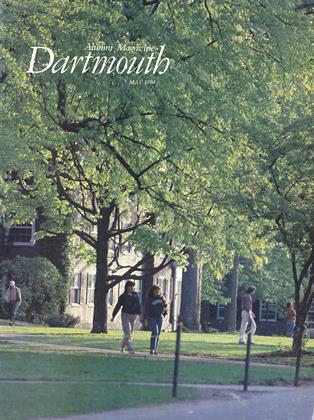

A group of well-educated, civilized explorers, hacking their way through a dense jungle, coping with insects, wild beasts, and superstitious natives, in hopes of discovering the ruins of an ancient civilization this is the stuff old movies are made of. But add some Dartmouth alumni, a.helicopter, and a sophisticated navigation device teamed with a satellite and you have a recent real-life expedition into the uncharted jungles of the Yucatan Peninsula in search of the cities of the Maya, Indians of southern Mexico and Central America whose civilization reached its height a millenium ago.

The adventure was the brainchild of Rod Frates '58, president of the C.L. Frates Insurance Company in Oklahoma City. "I read an article in National Geographic about some fellows thrashing around in the jungle in the Yucatan Peninsula searching for lost Mayan cities," said Frates. "The hardships and complicated logistics which an expedition on foot entailed seemed absurd in light of technical developments in satellite imagery." In 1980 Frates approached the Earth Satellite Corporation, of which he is a director, with the idea of using the imagery from the LANDSAT system in support of archeological exploration. Robert Porter '57 is founder and president of the Maryland-based company, a consulting firm which provides remote sensing expertise for a wide variety of applications, including geology, agriculture, and land use. Jon Dykstra, who earned a Ph.D. from Dartmouth in 1978, is one of the company's geologists. "For geologic applications," said Dykstra, "the LANDSAT imagery is used principally as a structural and spectral guide for mapping surface features associated with hydrocarbon or mineral deposits. However, the design of the LANDSAT imaging system is such that it is especially sensitive to variations in vegetation cover of the earth's surfaces." Using LANDSAT imagery, the group was able to locate six sites within the peninsula which appeared to have anomalous vegetation and which also showed evidence of accessible water at the end of the dry season. Based on the assumptions that the ancient Maya would be attracted to those areas where water was available year-round and that the ground disturbance would have altered the distribution and density of the various vegetation species, they believed that these anomalous image locations might represent sites of ancient Mayan civilizations.

Numerous problems had to be solved before the explorers could depart for Mexico. The thick rain forest cover of the area presented a formidable barrier to ground transportation. A two-engine helicopter was obtained along with a seasoned crew willing to fly with few reliable weather reports, visual flight references for navigation, suitable landing zones, or accessible spare parts and local maintenance. The limited range of the helicopter required that several caches of fuel be established in the jungle to allow refueling at intermediate points. A Global Positioning System (GPS) was borrowed from Magnavox with the permission of the Departments of Transportation and Defense. The GPS works with the NavStar satellite system to provide an instant update of the user's precise position in latitude, longitude, and elevation to within a 15-meter sphere. It has the ability to aim the helicopter directly to an inputted target location. "With this sort of logistical support,"said Dykstra, "it was a straightforward task to fly the helicopter directly over those sites which appeared anomalous on the LANDSAT imagery."

Accompanied by several Mexican archeologists, they established a base camp in Chetumal, Mexico. "Of the six LANDS AT targets visited, four still had standing architecture and clear evidence that they were indeed major Mayan sites; however, all four had been previously recorded by earlier archeological explorers," said Dykstra. Yet the group found that by flying 150 feet above the trees, they were able to spot "anomalous lumps" on the hillsides below. They examined these by landing in some tight spots, at one point sliding into a chili pepper field with 45 seconds of fuel remaining. "At one site," said Dykstra, "Rod belayed from the helicopter to stand on top of a large pyramid. Here he was to use a chainsaw to clear a landing path for the helicopter. However, Montezuma had revenge on the chainsaw, destroying it after the second tree and causing Rod to have to climb back up the rope out of the jungle and to the safety of the helicopter." Five of the areas they investigated were found to be previously undiscovered sites of Maya civilization. Three of these five were of substantial size, consisting of more than two pyramids and an extensive number of smaller, associated structures. "At least one of the significant new sites which we discovered will be excavated and restored," said Frates.

Other successes of the operation included demonstrating the application of high technology to archeological exploration and documenting an extensive ancient Mayan population within the southern portion of the Yucatan Peninsula. "The Mexican government has expressed an interest in better defining their archeological atlas of this area," said Dykstra.

In one of the earliest recorded meetings between the Maya and the "civilized" world, the explorers met with a less than cordial reception: a Captain Valdivia, sailing by in 1511, survived a shipwreck off the coast of the peninsula only to be sacrificed by the Maya to their moon goddess. Although they still eke out a primitive existence in the jungle, the modern day Maya are far more civilized. "They didn't think our helicopter was a mechanical god coming out of the sky," said Dykstra, "but it sure was exciting."

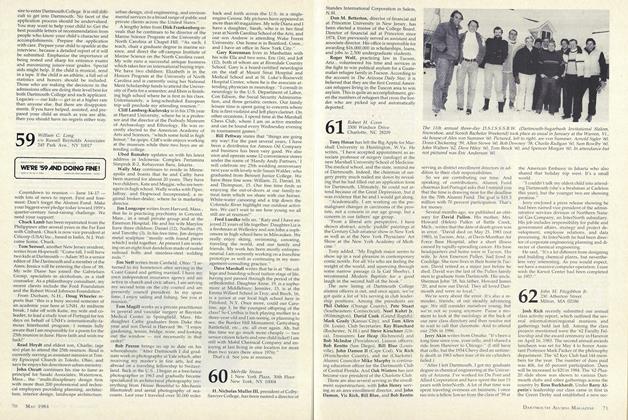

RodFrates '58 gives the thumbs up" signal while searching for Mayan ruins in the jungles ofthe Yucatan Peninsula by helicopter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFeast and Famine

May 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Feature

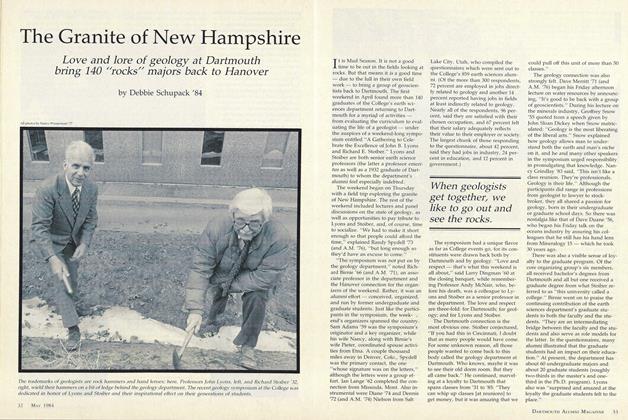

FeatureThe Granite of New Hampshire

May 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

May 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Return to Dartmouth

May 1984 By Brian W. Ford '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

May 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

May 1984 By Clement B. Malin

Article

-

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Almanack

February 1935 -

Article

ArticleMuseum Adds Rare Items

December 1939 -

Article

ArticleAppoint New Inn Managers

July 1951 -

Article

ArticleChasing the Best Burger

September | October 2013 By Lauren Vespoli ’13 -

Article

ArticleFrom the source to the sea: a cleaner Connecticut

NOVEMBER 1981 By Robert Linck -

Article

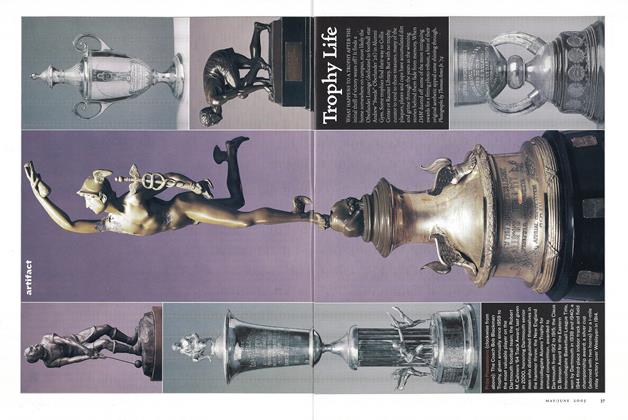

ArticleTrophy Life

May/June 2005 By Thomas Ames Jr., '74