Former President John Dickey used to describe the Dartmouth experience with the term "liberating arts." He proposed that a student's time at Dartmouth could liberate him from the prejudices brought from home. I think my classmates' and my education at Dartmouth has worked, in part because of the success of Dickey's liberating arts. We were not, however, just relieved of some of our prejudices. We were freed from a satisfaction with ourselves. At Dartmouth, we learned to respect what was beyond us more than our own selves.

This lesson of respect for what is beyond the individual came about largely through the intellectual discipline that is the core of a Dartmouth education. Anthropology Professor Hoyt Alverson has defined the purpose of the liberal arts institution as the promotion of critical thinking. During the debate about the appropriateness of our college symbols, this critical environment bore up new insights into respecting our fellows.

Against a background of opinion that treated "sensitivity" toward others as something inconsistent with the standards for "rigor" in the College's tradition, "sensitivity" in fact proved inextricable from critical thinking at Dartmouth. Thinking critically, we saw we could best measure the potential harmfulness of particular words and symbols not by simply recalling our innocent intent in using them, or by protecting ourselves with the waiver that we were only joking, but by inquiring how those words would in fact be interpreted by others.

These discussions also reminded us of the difference between rights and privileges— that the privileges allowing us to cling to nostalgic toys of the past, such as Indian symbols, or all-male alma maters for coeducational colleges, are secondary to the right of respect. The right to be respected is inalienable in a college community. It is something owed, not earned. And whether that right has been denied can only be truly ascertained by conferring with those whom the symbol depicts, not with those who are doing the depicting.

Here at Dartmouth our education went beyond a celebration of First Amendment protections; we learned that a critical and spiritual respect for others matters more than a legalistic whining for the right to behave irresponsibly—that individual freedom is important but that freedom is meaningless without an accompanying sense of community.

We also learned to respect our college, our elders, and the subtle mystery and significance of institutions in general. Raised on democratic values emphasizing rights and participation, we were eager to enjoy our new adulthood franchise at Dartmouth and were poised to mold the place for our own purposes. We remembered that we came to Dartmouth not to educate but to be educated. We shed our cocky, smug airs and settled down to learning. We came to remember that our selection of this place brought with it a commitment to and confidence in learning from it as an institution.

Part of that commitment meant welcoming heartily the leadership of our faculty and administration, and temporarily surrendering claims to democracy and caustic debate. The educative relationship is not a democratic one. It smacks of inequality, and rightly so. It presumes that the students are here to learn from a college that is in all senses bigger than they are.

We realized that this educative relationship required from us a faithfulness to all of Dartmouth. Even as we sought changes to improve the College, we recognized the need to respect all of its history, all of its weaknesses, and all of its strengths. It was, as we saw, in most ways as mixed and as good as we were.

That liberal arts lesson led to a further, more significant insight: a respect for how little we really know. Left between the extreme positions on divestment that ossified during the shanty affair, we began to appreciate the questioning spirit of Socrates. We realized that getting at the truth was something that required hard work. We learned an awe for wonder, a distrust for simplification, a sensitivity for the inherent complexity of things. We became skeptical of absolutist causes that obscure the grainy nature of the actual situation, or that veil the faults of the causists in robes of selfrighteousness. We learned, to distinguish those who pursue liberation as their end— but who were oppressive in their means— from those who sought a world of love by simply loving those around them.

As we began to be liberated from our own individual worlds, we were enabled better to respect our fellows, our college, and our limits in readily understanding the world around us. Dartmouth has not given us material knowledge. It has begun to give us spiritual wisdom. And this we must build upon.

Charles F. Moore IV 'B7 was co-chairperson ofthe Student Ad Hoc Committee on the AlmaMater and Class Orator before graduatingmagna cum laude in the spring. The essay isadapted from the address he gave on Class Day.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMystery on the Mountain

September 1987 By Daniel Q. Haney -

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

September 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87 -

Cover Story

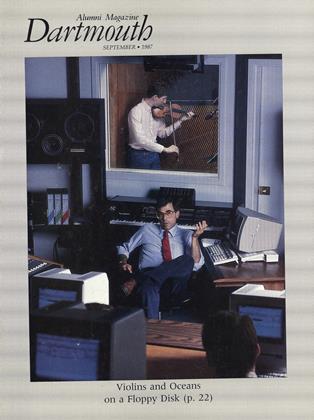

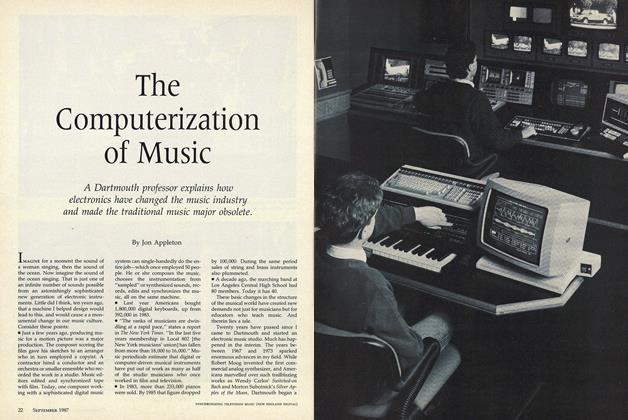

Cover StoryThe Computerization of Music

September 1987 By Jon Appleton -

Feature

FeatureThe Speech

September 1987 -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

September 1987 By Teri Allbright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1976

September 1987 By Martha Hennessey

Article

-

Article

ArticleFRATERNITIES SUSPEND ACTIVITIES FOR THE YEAR

November 1918 -

Article

ArticleENGLISH DEPT. PUBLISHES BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR ALUMNI

November 1923 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

April 1954 -

Article

ArticleSHOTMAKERS

July | August 2014 -

Article

ArticleUnited States Foreign Policy and Europe

June 1946 By JOHN C. ADAMS -

Article

ArticleThe Absolute and the Ambiguous

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84