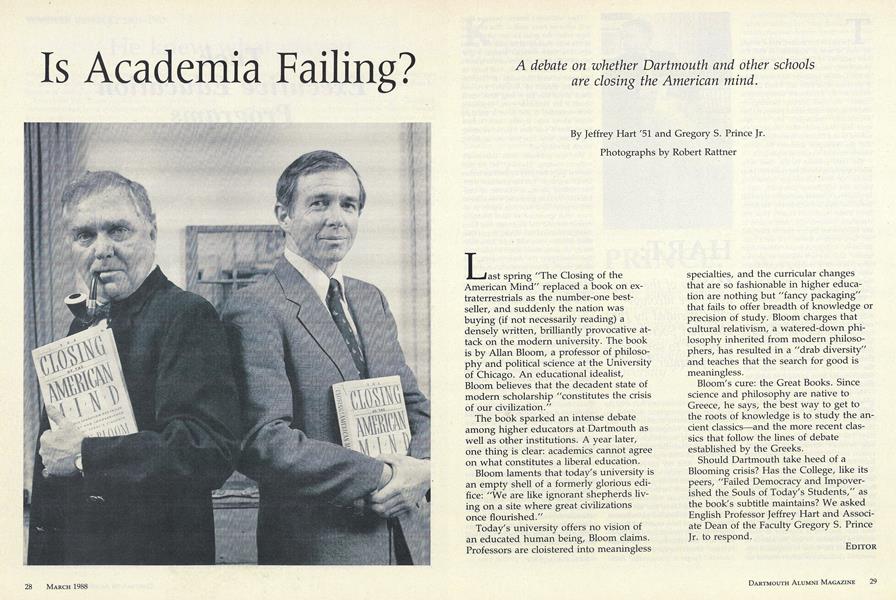

A debate on whether Dartmouth and other schools are closing the American mind.

Last spring "The Closing of the American Mind" replaced a book on extraterrestrials as the number-one bestseller, and suddenly the nation was buying (if not necessarily reading) a densely written, brilliantly provocative attack on the modern university. The book is by Allan Bloom, a professor of philosophy and political science at the University of Chicago. An educational idealist, Bloom believes that the decadent state of modern scholarship "constitutes the crisis of our civilization."

The book sparked an intense debate among higher educators at Dartmouth as well as other institutions. A year later, one thing is clear: academics cannot agree on what constitutes a liberal education.

Bloom laments that today's university is an empty shell of a formerly glorious edifice: "We are like ignorant shepherds living on a site where great civilizations once flourished."

Today's university offers no vision of an educated human being, Bloom claims. Professors are cloistered into meaningless specialties, and the curricular changes that are so fashionable in higher education are nothing but "fancy packaging" that fails to offer breadth of knowledge or precision of study. Bloom charges that cultural relativism, a watered-down philosophy inherited from modern philosophers, has resulted in a "drab diversity" and teaches that the search for good is meaningless.

Bloom's cure: the Great Books. Since science and philosophy are native to Greece, he says, the best way to get to the roots of knowledge is to study the ancient classics—and the more recent classics that follow the lines of debate established by the Greeks.

Should Dartmouth take heed of a Blooming crisis? Has the College, like its peers, "Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today's Students," as the book's subtitle maintains? We asked English Professor Jeffrey Hart and Associate Dean of the Faculty Gregory S. Prince Jr. to respond.

EDITOR

The fact of the matter, and it would be well to face it squarely, is that the vast majority of Dartmouth seniors are profoundly uneducated. Students come to the College ignorant and they leave it ignorant. This past fall, I had 23 students in my Freshman Composition course. We read Milton, Hemingway and Frost (my curriculum, today, is thus whimsically traditional), and we also read and discussed Allan Bloom. I resolved to test Bloom's bestselling thesis that the American academy has deliberately created a cultural wasteland.

The only student in the class who knew anything about, for example, John Locke, or who could say something about the Mayflower Compact, was a freshman of Chinese extraction who had been educated in South Korea. He knew more about American history than the American students did. Any notion of the natural-law theory that lies behind the "self-evident truths" of the Declaration of Independence—"self-evident truths" that are self-evident to anyone who has even a nodding acquaintance with Western thought—as I say, any such notion is Terra Incognita to my pleasant freshmen.

Oh, they have political opinions of various sorts, even some thoughts about religion, but they entirely lack even the rudiments of intellectual literacy. Their opinions, such as they are, are based on air. The tragedy is that at Dartmouth nothing much will change for most of them. As seniors, most of them will lack the elementary intellectual tools that would enable them to begin to think seriously.

My students know where they are geographically: Hanover, New Hampshire. They do not now and most of them will not possess even the faintest clue as to where they are in human history. The great, turbulent creative tension between Athens and Jerusalem, reason and revelation, is, again, Terra Incognita. My students do not know who they are, because they do not have any idea of the civilization that has gone before them. It's as if we are asking them to reinvent the wheel, make fire again with a bow-and-spike.

As Bloom observes, many of the students are ideologically offended by the idea that Socrates is superior to some tom-tom pounder, or that the Athens of Pericles and the Rome of Augustus represented civilizational achievements superior to most others, and that only the West has a philosophical tradition including systematic thinkers like Spinoza, Kant and Wittgenstein. Benjamin Disraeli was not thus diffident. When a fellow Englishman sneered at Disraeli's Jewishness, Disraeli replied: "Yes, I am a Hebrew. And my ancestors were priests in the Temple when yours were painted blue and howling at the moon."

My Dartmouth freshmen, most of them, will graduate without knowing anything about Locke and his decisive Whig theory of limited government. They will never have heard of Livy, the most frequently quoted author in the debates over the ratification of the Constitution. Montesquieu? Forget it. Aristotle? Forget it. Tocqueville? Zilch.

They will never absorb, because they will not ever have read it, that scene in Troy when the great Hector takes leave of his wife Andromache and his infant son. The baby Astynax weeps, frightened by the black plumes on his father's helmet. His father's body will soon be dragged around the walls of Troy behind the chariot of Achilles. You can think about this for a long time, think about it for centuries even, beginning with Aristotle, if you have a mind to think about war, loyalty, love, father-hood. But if you don't know anything important, how can you say anything worth listening to?

You can graduate from Dartmouth without reading "Hamlet," or, for that matter, any other play by the best writer in our language. You can graduate without reading Dante, or Goethe, or Dostoievski. You can graduate, with a liberal arts degree, God save the mark, in almost total ignorance of what Matthew Arnold termed the best that has been thought and said. No doubt, if you take Black Studies, you will read Toni Morrison, or some such stuff. Please pass the Vonnegut, the Ann Beattie, the comic strips. Don't even ask what they read in Women's Studies, beyond the fig-leaves, or how it is presented. Don't even ask.

The fact that a recent survey ranks Dartmouth sixth among the nation's colleges and universities is not reason for rejoicing. If Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford and Berkeley are thought to be in some measure a bit better, then what can "better" possibly mean? If Penn and Brown and Cornell and Michigan and Chicago are fulfilling their educational responsibilities to an even lesser degree, then just how bad can things get? Contemplating the vast inertia, the cultural ignorance, the suffocating presentmindedness and the sleazy intellectual assumptions that are all around us, one can feel only a vast depression. There is a great deal of work to be done, a work of fundamental educational reconstruction.

Do not misinterpret me. Every year, Dartmouth seniors do graduate who have managed to get a first-class education, quite probably as good as any available in the Western world. This handful of seniors will have shaped their schedule depending upon the student grapevine and upon faculty members willing to tell them the truth. They will have taken Saccio and Kastan on Shakespeare, and Jastrow on cosmology and evolution. They will have heard of Kevin Brownlee's superb Dante course, backed up by the Dartmouth Dante Project, which has pioneered in putting on computer the most important Dante commentary since the fifteenth century.

Such students find out about Greek and Latin Studies, and about a few good courses in history and philosophy. They find out about Humanities I and II. Quite possibly a couple of dozen seniors leave Dartmouth with the rudiments of a serious education. The College itself, in its official posture that push-pin is as good as Pushkin, has not helped them. Except for a few seniors, the rest go forth, zombie-walking through the hall-ways of the mind. Dartmouth has the potential of being the best liberal arts college in the nation, but only if it can begin to take itself seriously. This will need a sense of possibility, and a nononsense executive will.

Professor Bloom's prescription is a university resembling Plato's Symposium, in which friends—this is a tremendously important concept in ethical thought—discourse on the great questions of beauty, truth, love, death, immortality, and God. Thought itself is ecstasy and human completeness.

But in the foreground is the university we actually have. Bloom's description of it is horrifying. Out of his ideal love for what the university could be, Bloom has told the brutal truth about what it actually is. Bloom knows and tells his readers how this nation, and the West, is being morally and culturally gassed by its intellectual and academic elites.

Let us think first about Bloom's idea of the university—as noble, powerful and poetic as any hymns to Oxford written by Cardinal Newman or Matthew Arnold: "When I was 15 years old I saw the University of Chicago for the first time and somehow sensed that I had discovered my life. I had never before seen, or at least had not noticed, buildings that were evidently dedicated to a higher purpose, not to necessity or utility, not merely to manufacture or trade, but to something that might be at an end in itself."

Contrasting sharply with this noble purpose is Bloom's vitriolic portrait of today's "student." In my own experience of teaching at Dartmouth, I would say that, with some outstanding and infrequent examples, Bloom is entirely accurate. "There is one thing a professor can be absolutely certain of: almost every student entering the university believes, or says he believes, that truth is relative." Enter Professor Bloom, fully armed with all the earned weapons of Western philosophy:

The students, of course, cannot defend their opinion. The best they can do is point out all the opinions and cultures there are and have been. What right, they ask, do I or anyone else have to say that one is better than the others? If I pose the routine questions designed to confuse them and make them think, such as, "If you had been a British administrator in India, would you have let the natives under your governance burn the widow of a man who had died?" they either remain silent or reply that the British should never have been there in the first place.

As Bloom puts it in his subtitle, higher education has failed democracy and impoverished the soul of today's students. But Bloom gets it only half right with his discussion of "openness." Modern education, he writes, "pays no attention to natural rights or the historical origins of our regime, which are now thought to have been flawed and regressive. . . . It is open to all kinds of men, all kinds of lifestyles, all ideologies. There is no enemy other than the man who is not open to everything." Well, that is the public face of the ideology. "Openness" applies only to the left. We are to be "open" to Castro or to Stalin, but Hitler has become a religious category, a guarantee of the existence of evil. The left always offers the possibility of a better world.

Young Americans, even Bloom's elite students at the University of Chicago, "know much less about American history and those who were held to be its heroes" than past generations did. There has occurred a homogenization of American culture. "Practically all that young Americans have today is an insubstantial awareness that there are many cultures, accompanied by a saccharin moral drawn from this awareness: We should all get along. Why fight?"

It is fashionable for the elite universities, Dartmouth being no exception, to require a course in "non-Western" culture. But as Bloom shows, "if the students were really to learn something of the minds of any of these non-Western cultures—which they do not—they would find that each and every one of these cultures is ethnocentric. All of them think their way is the best way, and all others are inferior."

Right there is the intellectual turn within the turn. The very anthropological perspective that allows us for one moment to relativize and "appreciate" these cultures is itself Western and "higher." There is no Chinese anthropology that "appreciates" and "respects" Vietnamese culture. There is no Moroccan or Albanian anthropological perspective. In its academic apotheosis, Western culture is the only culture that does not celebrate its own ways and its own achievements. It keeps looking for some Zimbabwean Mozart. Bloom says: "It is important to emphasize that the lesson the students are drawing from their studies is simply untrue. History and the study of cultures do not teach or prove that values or cultures are relative. All to the contrary."

And yet we have undergone a civilizational lobotomy. "By the mid-Sixties universities were offering students every concession other than education, but appeasement failed and soon the whole experiment in excellence was washed away, leaving not a trace." Serious reading, foreign language, and other academic requirements were jettisoned; the Ivy League, with Brown University in front of the Gadarene swine, led the way.

Bloom's great theme throughout is that ideology has invaded the academy to an absolutely unprecedented degree, closing the American mind, at least the academic American mind, to the truths about human nature as it actually is and has aspired to be.

It is not exactly clear from Bloom's book how the university can escape its present cultural and spiritual anarchy. His answer is essentially Matthew Arnold's, though informed with greater philosophical knowledge than Arnold had at his disposal. Professor Bloom puts his faith in the "saving remnant" who will lead the philosophical life within the American academy. He regards the activity of philosophy as good in its own right, the activity of thought informed by the great books.

It is the philosophical life to which the saving remnant must aspire, the continuing reexamination of those great questions, the activity of reexamination itself constituting the peak of civilization.

And yet the very book that looks to the university for salvation contains one of the most savage indictments of the contemporary American academy. It is conceivable but not very plausible that the civilization of the West will be revived by some impulse from these centers of moral and intellectual corruption. There are, no doubt, great isolated professors like Allan Bloom, but modern universities—including Dartmouth are, quite simply, out of business, intellectually, at least for the time being.

Jeffrey Hart '51 is a professor of English atDartmouth and a senior editor of the National Review. His latest book is "From ThisMoment On: America in 1940"( Crown Publishers).

Knowing truth is more comfortable than seeking truth. In seeking, one can become lost or, even worse, can never arrive. Allan Bloom, as author, and Jeffrey Hart, as reviewer, argue that in the last half of the twentieth century the university has lost itself in the labyrinth and is unlikely to emerge. As modern-day Henry Adamses, author and reviewer alike lament the failure of education in the United States to create order out of chaos, to forge unity from diversity, to provide absolutes in the midst of uncertainty. Bloom sets out to restore order.

The bestseller lists and Jeffrey Hart's review demonstrate that many believe Bloom succeeded. The believers are wrong. In the end, the order Bloom tries to establish closes the American mind more than opens it.

Bloom argues that restoration and salvation—the path from the labyrinthwill come only when universities rediscover the essential discourse of our culture and civilization expressed most clearly in western philosophy. That discourse reveals to Bloom underlying values and absolutes that are an antidote to today's relativism and loss of values. The philosophical discourse about the nature of human nature, he argues, represents the heart of western civilization.

As a philosopher, Bloom sees knowledge as a pyramid with philosophy and its insights about knowledge and human nature at the pinnacle. This hierarchy of thought requires a similar hierarchy of cultures and values; to Bloom, all cultures cannot be equally valid.

These untested assumptions lead in a surprisingly unphilosophical way to the gross generalizations which infuse this book and which Professor Hart enjoys so much. In an earlier essay, Hart quotes uncritically one of the typically outrageous generalizations of Bloom's jeremiad against contemporary education: Sexual adventurers like Margaret Mead and others who found America too narrow told us that not only must we know other cultures and learn to respect them, but we could also profit from them. We should follow their lead and loosen up, liberating ourselves from the opinions that our taboos are anything other than social constraints. ... All such teachers of openness had either no interest in or were actively hostile to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Did all scholars who believed they could profit from knowing the culture of Japan, China, India or Mexico really ignore or attack the Declaration of Independence? Is western culture truly the only culture that does not celebrate "its own ways" as Hart claims?

Dartmouth College, along with many other universities, has answered Bloom with a clear, firm no. With 29 language and foreign-study programs and with more than half of each class studying at least one term in Europe, Dartmouth's curriculum not only celebrates western civilization but also provides students an intense opportunity to study it first-hand.

In addition, Dartmouth has more students studying in China than any other undergraduate-degree program in the United States, it has strong interdisciplinary programs such as Native American Studies and Asian Studies, and it has exactly the sort of non-western requirement that Bloom scorns. Through these programs Dartmouth, like most universities, has asserted the principle that knowing other cultures does benefit us (a defense that has been stated explicitly in a brochure that the Faculty of Arts and Sciences recently published, titled "What Education Has to Impart.")

For Bloom, the emergence of new fields like Women's Studies or Native American Studies, both represented at Dartmouth, extends the subversion brought on by the study of diverse cultures. Such fields cannot even find a place in Bloom's hierarchy of knowledge. For Bloom and for Hart, the final result of this "openness" is a generation which holds no truths, which accepts all cultures just as it accepts all knowledge as equal, and which ultimately denies the superiority of western civilization. The American mind (for Bloom America includes only the United States) has closed itself to the stability and beauty of its philosophical tradition. It has abandoned the power of the pyramid for the formlessness of the circle. Moreover, he argues, the university refuses to assert its power to open the closed door, to rebuild the pyramid.

That "American Mind" should have made the bestseller list testifies to how much the public enjoys Bloom's message. The academy, which traditionally has been society's critic, has been examined and found wanting, and even may be the cause of this society's problems. In Bloom's terms higher education has perpetuated a moral relativism that undercuts values, weakens the family, and encourages lasciviousness along with who knows what other ills. The public, which in an earlier time denied Socrates, enjoys immensely the current discomfort of the university.

Problems and discomfort do exist in universities in general and at Dartmouth. Students do not have enough basic knowledge about the classics, as Professor Hart correctly asserts. Nor do they have enough knowledge about science, non-western culture or many other fields fundamental to modern education.

What Allan Bloom and Jeffrey Hart do not appreciate is that some of the causes of the problem are the very strengths of higher education in the United States. That is why so many of the goals that James O. Freedman has identified as crucial for Dartmouth correspond so closely to the trends that Bloom laments. Developing a sensitivity to and knowledge about other cultures, establishing a more diverse student body, promoting neglected scholarly approaches implicit in fields like Women's Studies, encouraging interdisciplinary academic ventures as diverse as Native American Studies or a laser chemistry-physics laboratory enrich, rather than destroy, the discourse about the human purpose, which Bloom correctly argues should be the heart of education. In the process of enriching the discourse, however, these trends have created confusion and unease because of the explosion of knowledge and the new approaches they bring. In response, universities are having trouble maintaining a sense of coherence and selecting the essential core that should be taught in light of these new intellectual opportunities.

Neither Bloom nor Hart seems willing to analyze the irony that universities exist to generate these very problems. Universities must do more than transmit culture. They must shape and create culture—pass what is known through a process which sloughs off and yet preserves what at the moment is judged not to be universal and abiding and which replaces it with what is hoped will prove profound for some future generation. Students must be exposed to all parts of the process. What is on the fringe one

day—John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz working with some strange new computer language; Charles Drake working on an even stranger theory about continents floating on the face of the Earth; Vincent Malmstrom presenting evidence that the compass existed in Central America hundreds of years before the Chinese "discovered" it; Errol Hill writing about Black Shakespearean actors and Blanche Gelfant about women writers in Canada—may prove to be in the mainstream in a few years. Students must be exposed to all parts of the process.

If Bloom's heroes—Plato, Socrates, Rousseau and Locke—were to return to a university today, I suspect they would be just as likely to elect courses in African & Afro-American Studies as to enroll in Professor Bloom's course. As seekers of truth, they would find a rich and profound source of new material to aid them in analyzing the great issues of all literature and philosophy—what it means to be human, the nature of evil and good. While the philosophers certainly would have appreciated what "Hamlet" had to say about moral responsibility, they would have found their own discourse on that subject enriched by exploring, for example, the cultures of a distant world through a work such as Chinua Achebe's "Things Fall Apart," a contemporary novel assigned to all members of the class of 1990 during Freshman Week at Dartmouth. "Hamlet" and "Things Fall Apart" come from different ages and different cultures but explore the same timeless questions about the human will, fate, tragedy and responsibility.

In response to this line of argument, Bloom might note gleefully that I provide the perfect example of the perversion of relativism. Isn't Prince saying that only process matters, that there are no absolutes, that students can study what they want? The university relativist, as starkly painted by Bloom, finds Navajo ritual songs the equal of the "Odyssey," "Things Fall Apart" the peer of "Hamlet."

No charge could be more false. The core of the university in all ages has been the belief that truth and absolutes do exist, no matter how imperfectly we may see them or how often we may fail to identify them. The student is better able to appreciate the quality of "Hamlet" for having compared it with "Things Fall Apart" and vice versa. Professors must demand of students—and students must demand of professors—that they

be prepared to take a stand and select one as being "better" literature than the other. Their understanding of what it means to call a work "profound" will be strengthened by having read both works, if the analysis and comparisons are approached with rigor, sensitivity and insight.

Bloom assumes that the new fields lack this rigor; but clearly subject matter does not determine rigor, even when the subject is Plato or Socrates. The questions asked in the new and emerging fields are no less profound than those asked in Philosophy and Religion. Native American Studies, Women's Studies and Afro-American Studies are essential to the university. They are part of the testing and questioning of accepted tradition in the search for what is truly the core of human nature and experience. They are central to what makes a university an "uncomfortable" place.

Professor Hart shudders at the thought of asking what the students might be reading in Women's Studies. Bloom at least acknowledges the feminist research in writers like Rousseau, but calls it "the latest enemy of the vitality of classic texts." Bloom complains that feminism undercuts the capacity of students to appreciate the heroic. This is just the point. Feminist research has broadened and enriched the contemporary debate about what is heroic and noble, just as it has helped us understand a similar debate that took place between writers like Rousseau and Diderot. Bloom lacks faith in the students' ability to define what is noble. He does not even entertain the question Brecht raised in his play, "Galileo." "Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero," a character says. Galileo replies, "No, Andrea, unhappy is the land that needs a hero."

If the university curriculum is enriching the essential discourse after all, are the students incapable of participating in it, as Bloom argues? He begins with what Professor Hart celebrates as a great opening sentence: "There is one thing a professor can be absolutely certain of: almost every student entering the university believes, or says he believes, that truth is relative." The students will have to defend themselves. From my own experience, I can say that when the freshman class examined an ethics case focusing on issues about death and dying prepared by Dartmouth's Institute for Applied and Professional Ethics, many students in the groups with whom I worked accepted that truth and

absolutes exist. However, they were somewhat more in awe than Bloom of how hard it is to find those absolutes and to apply them. Socrates and Plato, unlike Bloom and Hart, would have empathized with these students.

To explore, to celebrate the values of new fields or other cultures—and even to be confused about what is fundamental—does not mean that nothing is fundamental and all has become relative in the university. The university, as its name should imply, has as a central premise that no culture is sufficient unto itself and that all may contribute something to the whole. President Freedman argued succinctly in an address to the general faculty that we all, to some extent, stand on the shoulders of others. The danger is not in moral relativism; the danger comes in closing one's mind to the insights that other cultures, disciplines, and even political ideologies can provide. Thus the circle is not formless. It symbolizes the infinite connections which exist between disciplines, the evolution of knowledge over time, and the wholeness that must be a part of the truths that we seek.

As part of the process of exploration, we must give students the means and the courage to make judgments. In that respect, Bloom speaks for all of us. He may be right (though I doubt it) that this generation does not share the excitement of the intellectual life to the extent that earlier generations of students did. I am persuaded, as is Bloom, that the university exists to try to instill that excitement. I also am persuaded that we can demand more of ourselves and our students as a way of exciting them to learn more. However, we will succeed only if we accept that what we seek is the whole truth and not simply the vision of a single tradition perched at the top of a pyramid. Bloom should heed Hamlet's warning to Horatio:

And therefore as a stranger give it welcome,

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

HART:"Many of the studentsare ideologicallyoffended by theidea that Socrates issuperior to some tomtompounder."

PRINCE: "The public, whichin an earlier time deniedSocrates, enjoysimmensely the currentdiscomfort of theuniversity."

Gregory S. Prince Jr. is Dartmouth's associate dean of the faculty for academic planning and resource development. He is alsoan adjunct associate professor of history. Thebrochure published by the Faculty of Arts andSciences, "What Education Has to Impart,"is available free from 201 Wentworth, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire05753.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

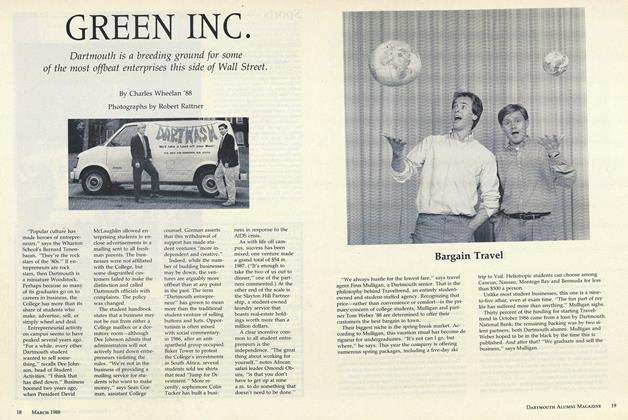

Cover StoryGREEN INC.

March 1988 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureHe Knew what Played

March 1988 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

March 1988 By Sally Goggin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

March 1988 By Charles D. Vernon -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

March 1988 By Kenneth M. Johnson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

March 1988 By Monk Larson

Features

-

Features

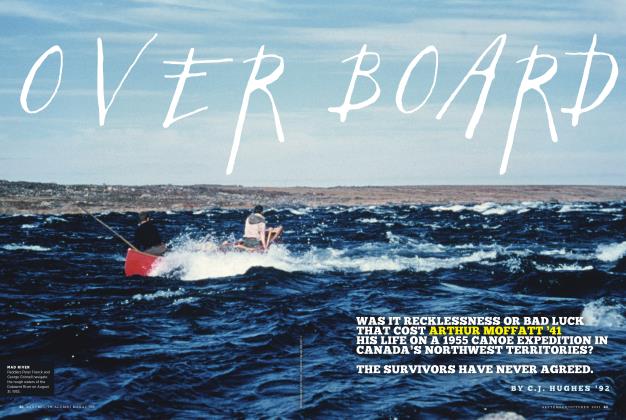

FeaturesOverboard

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

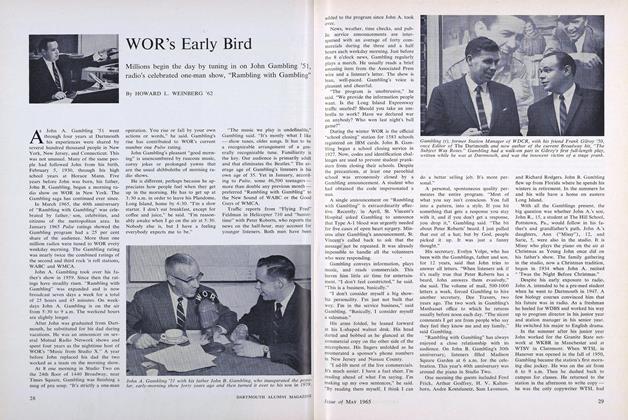

FeatureWOR's Early Bird

MAY 1965 By HOWARD L. WEINBERG '62 -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

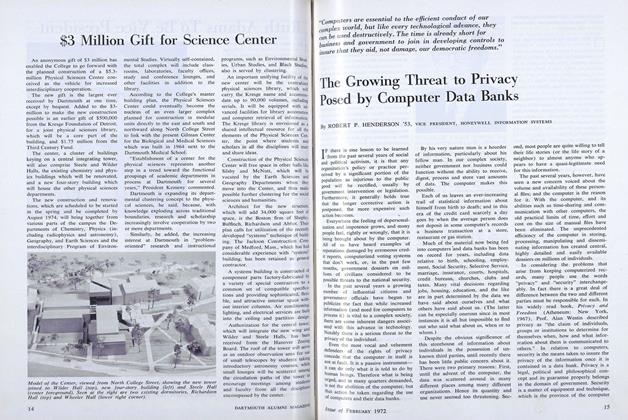

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

FEBRUARY 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

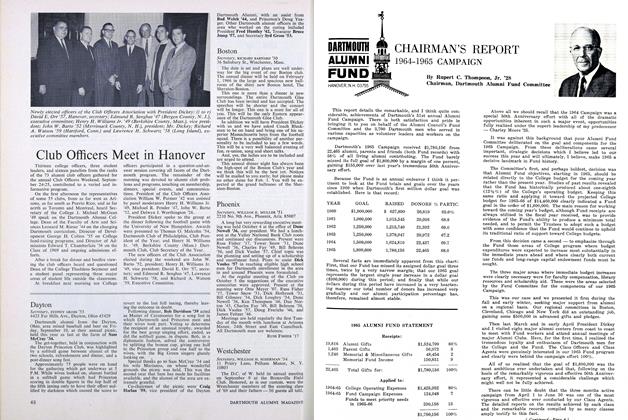

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28