Dartmouth is a breeding ground for someof the most offbeat enterprises this side of Wall Street.

"Popular culture has made heroes of entrepreneurs," says the Wharton School's Bernard Tenenbaum. "They're the rock stars of the 'Bos." If entrepreneurs are rock stars, then Dartmouth is a miniature Woodstock. Perhaps because so many of its graduates go on to careers in business, the College has more than its share of students who make, advertise, sell, or simply wheel and deal.

Entrepreneurial activity on campus seems to have peaked several years ago. "For a while, every other Dartmouth student wanted to sell something," recalls Dee Johnson, head of Student Activities. "I think that has died down." Business boomed two years ago, when President David McLaughlin allowed enterprising students to enclose advertisements in a mailing sent to all freshman parents. The businesses were not affiliated with the College, but some disgruntled customers failed to make the distinction and called Dartmouth officials with complaints. The policy was changed.

The student handbook states that a business may not be run from either a College mailbox or a dormitory room—although Dee Johnson admits that administrators will not actively hunt down entrepreneurs violating the rules. "We're not in the business of providing a mailing service for students who want to make money," says Sean Gorman, assistant College counsel. Gorman asserts that this withdrawal of support has made student ventures "more independent and creative."

Indeed, while the number of budding businesses may be down, the ventures are arguably more offbeat than at any point in the past. The term "Dartmouth entrepreneur" has grown to mean more than the traditional student venture of selling buttons and hats. Opportunism is often mixed with social commentary: in 1986, after an antiapartheid group occupied Baker Tower to protest the College's investments in South Africa, several students sold tee shirts that read "Jump for Divestment." More recently, sophomore Colin Tucker has built a busi ness in response to the AIDS crisis.

As with life off campus, success has been mixed; one venture made a grand total of $54 in. 1987. ("It's enough to take the two of us out to dinner," one of the partners commented.) At the other end of the scale is the Slayton Hill Partnership, a student-owned laundry service that boasts real-estate holdings worth more than a million dollars.

A clear incentive common to all student entrepreneurs is theindependence. "The great thing about working for yourself," notes African safari leader Omondi Obura, "is that you don't have to get up at nine a.m. to do something that doesn't need to be done."

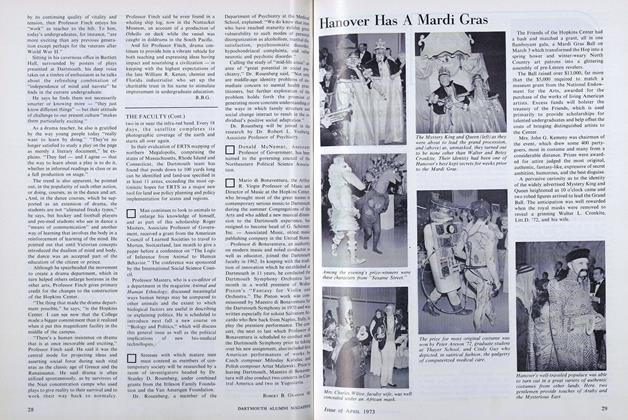

"We always hustle for the lowest fare, says travel agent Finn Mulligan, a Dartmouth senior. That is the philosophy behind Traveltrend, an entirely studen- towned and student-staffed agency. Recognizing that price—rather than convenience or comfort—is the primary concern of college students, Mulligan and partner Tom Weber '88 are determined to offer their customers the best bargain in town.

Their biggest niche is the spring-break market. According to Mulligan, this vacation ritual has become de rigueur for undergraduates. "It's not can I go, but where," he says. This year the company is offering numerous spring packages, including a five-day ski trip to Vail. Heliotropic students can choose among Cancun, Nassau, Montego Bay and Bermuda for less than $500 a person.

Unlike most student businesses, this one is a nineto-five affair, even at exam time. "The fun part of my life has suffered more than anything," Mulligan sighs.

Thirty percent of the funding for starting Traveltrend in October 1986 came from a loan by Dartmouth National Bank; the remaining backing was by two silent partners, both Dartmouth alumni. Mulligan and Weber hoped to be in the black by the time this is published. And after that? "We graduate and sell the business," says Mulligan.

On the afternoon of October 19, Alpha Delta Fraternity was practicing on the Green for an intramural football game when a passerby shouted, "Hey, did you hear the market's down 300 points?" The next huddle had nothing to do with football. Instead, the brothers turned their attention to their mutual fund.

"We should not sell in a panic," cautioned the quarterback. "Our portfolio is not leveraged, and we can afford to wait this one out." With business out of the way, the scrimmage continued.

The Alpha Delta Mutual Fund was started in the summer of 1986 while the founders were studying for an economics exam in money and banking. Seniors Frank Comas, Bryan Weidner, Andy Axel, Brett Matthews, Jay Henry and Charles Wheelan each agreed to invest $300. The six partners raised a couple thousand more by selling $25 shares to other students, and they plunged into the stock market.

The partners receive no commission, and the fund does not pay dividends. Profits are reinvested, and the entire portfolio will be liquidated and paid out to stockholders on June 1. "The only promise we made was to send out a newsletter to the stockholders once a term," says Bryan Weidner. "For college students, the mail alone was worth the investment."

At the peak of the bull market, the fund had gained 31 percent. The crash was a setback, but the damage could have been much worse. "We came out in better shape than most others because we had a sound strategy all along," says Jay Henry. "Throughout the bull market we sold for healthy profits rather than waiting for the big kill." By the time Black Monday rolled around, the fund was two-thirds cash. "In retrospect, our strategy was excellent," Weidner observes.

The fund does not mature for another three months, and the partners have assumed a conservative postcrash strategy. "It's risky to get back into the stock market any time soon," asserts stockholder Larry Whittemore. "I think that money might be sitting in the bank for a while."

For $40 to $250, Ed Gray '88 will set up his computers and state-of-the-art audio equipment and perform a one-man show in a dormitory, sorority or fraternity house. The music ("hack new wave," he calls it) is all preprogrammed, but Gray is a performer at heart. "I could just turn on my music and let it rip," he says, "but I usually do other things—hold up cards with lyrics." He can even be persuaded to break dance. In a recent performance, Gray was strutting back and forth behind his keyboard (which was playing itself) when he accidentally kicked out the plug and shut down the whole system. This is the hazard of modern music.

Gray, who is president of the marching band, also plays tuba, piano, banjo, and various percussion instruments. The one thing he does not do is read music. "I took piano for five years and faked it," he admits. "I play by ear." The transition to electronic music came when he took a course from Music Professor Jon Appleton, a man Gray describes as "the god of electronic music."

A summer of investment banking made his business possible. He used his earnings from an internship at Goldman Sachs in New York to buy $3,500 worth of equipment. The business branched into radio advertising when he did a spot for the Hanover pizza parlor Everything But Anchovies. "I heard their commercial on the air and I thought it was so bad that it moved me to approach them," says Gray. He integrated his music into a 30-second radio spot and presented it to the management, who immediately bought it.

A Russian major, Gray spent a term his junior year in the Soviet Union. He hopes to combine his two chief interests after graduation. There is a huge hidden market in the Eastern Bloc for electronic equipment, Gray observes. "I have to be one of the very few people who know this much about electronic music and Russian. Then again, I might find that is too specific and end up with some weenie corporate job until I get my feet on the ground."

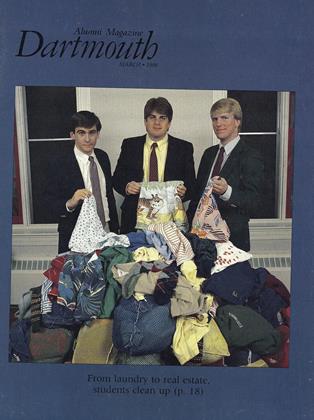

"We do laundry, but we're really into real estate," explained senior Rob Pedrero blithely last semester. With the help of '85 graduate Mike Davidson, Pedrero and fellow seniors Jeff Acker and Dave Roth have turned dirty clothes into a modest real-estate empire.

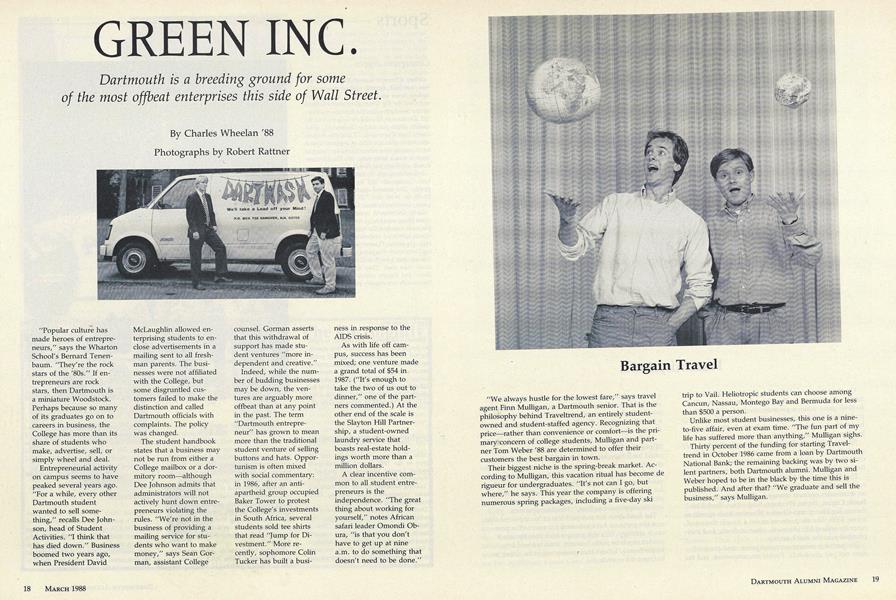

The students launched their laundry business, called Dartwash, in the summer of 1986. The company promised Dartmouth students clean clothes for only $55 a term. Since then the business has diversified: the partners now own and operate 11 apartment buildings in the Hanover area.

The laundry business currently grosses $40,000 annually and takes a load off the minds of some 150 customers per term. The Dartwash van collects bags of clothing once a week and takes them to a West Lebanon laundromat where ten to 12 students are paid an hourly wage (and given rolls of quarters) to wash.

Nine-tenths of the customers are men; according to Pedrero, women are hesitant to entrust Dartwash with sweaters and more delicate items. However, he alludes to one daringly dressed client who has Dartwash employees fighting among themselves for the right to fold her lingerie.

Dartwash was only a steppingstone for the three entrepreneurs. They recently sold the business to sophomore Dave Kelsey and formed the Slayton Hill Partnership. Roth's father co-signed a loan allowing the group to purchase its first building, and that property has been used as collateral for subsequent loans totalling well over a million dollars. The partnership now owns 76 rental units. The three students are completely responsible for renting, maintaining and insuring each building.

The business has its down side. "A lady will call up ten times because her refrigerator light doesn't work," Pedrero complains. Nonetheless, he and Acker plan to stay in the area after graduation, devoting two years to the Slayton Hill Partnership before business school. (Roth is applying to law school.)

Is there room in New York for a Dartwash Tower?

Omondi Obura '88 is the only Dartmouth entrepreneur who has had to fight a brush fire in the course of business. Obura leads safaris, and when a fire broke out in the Masai Mara Game Park in Kenya, he joined the effort to control the blaze. Obura has organized and will lead four African safaris this summer, three for Dartmouth alumni and one for graduating seniors.

The Kenya-born senior first heard of Dartmouth when his family hosted several students in the environmental studies program. After he enrolled at the College he continued the profession he had conducted since childhood, leading tourists through game parks. It is only recently, however, that Obura decided to offer his services to the Dartmouth community. "I figured it would be more fun to bring my own groups over," he explains.

The summer safaris will consist of five to 25 people. A Chicago-based company called African Classics provides brochures, makes travel arrangements, and pays for half of Obura's advertising expenses. He plugs his safaris with on-campus posters and slide shows. The excursion for Dartmouth alumni carries a price tag of $3,595 per person, which includes luxurious accommodations. Graduating seniors will rough it a bit more for $2,600.

For Obura, the most difficult part of a safari is nocturnal activity—of tourists, not animals. As tour guide and host, he often finds himself closing the bar with a different member of the trip each night, and then heading off to find game at six a.m. In the wee hours, Obura's Dartmouth background can come in handy: on one occasion he taught a member of the British Parliament to play beer pong.

Colin Tucker '90 spent the Yale football game last fall selling to alumni in the stands. He wasn't hawking popcorn; his product is Big Green Condoms. In what may be the ultimate act of student opportunism, Tucker has built a business out of safer sex.

The idea evolved during a conversation about sexual safety with his parents. Tucker reasoned, "Everything else in Hanover says Dartmouth on it. Why not condoms?" His parents raised no immediate objections to their son's peddling prophylactics on campus, according to the Dartmouth sophomore. "They weren't too worried because they didn't think I would do it," he explains. "That was before a large box from a condom company arrived on the doorstep." Despite the name, the condoms themselves have no writing or special coloring on them; the gimmick is in the packaging, which closely resembles a matchbook—an inspired bit of social camouflage.

Valentine's Day and Winter Carnival are peak sales periods. So is football season. Last fall six alumni bought 30 condoms apiece "to pass out to friends at home," Tucker reports.

Still, he has not exactly cornered the safer-sex market. Dartmouth itself is his biggest competitor. While Tucker has to hustle his product for a dollar apiece, the College has begun providing condoms at registration and in the Reserve Corridor of Baker Library free of charge.

It is the ideal case study for a class in business ethics: Balloonatics, a firm owned by Dartmouth students, has received an order to deliver a dozen balloons to a sick child at Mary Hitchcock Hospital. The students deliver the balloon bouquet and make a child's day. Minutes later they discover they went to the wrong room.

"You can't take the balloons away from the kid," says John Jenkins '88, co-owner of Balloonatics. Instead, he and his partner, Brett McDonald '88, quickly blew up a second batch and ate the loss.

Then there was the time two guys ordered balloons for the same girl on the same night ....

The balloon business has had its ups and downs since Jenkins and McDonald bought the firm from Andy Head 'B6 in the spring of 1986. Since then they have dressed up in Halloween costumes, visited birthday parties, decorated for a bar mitzvah, and gone wherever their deliveries have taken them. They have their limits, however: "We don't sing," says Jenkins.

Though neither partner plans to deliver balloons for a living, McDonald is leaning toward brand management, a profession that employs many of the skills he has polished in the past couple of years. In the meantime, the income keeps the partners in spending money. They charge $13 for a dozen balloons delivered anywhere on campus. Helium, their largest expense, costs about 11 cents per balloon.

Last spring break, Jenkins and McDonald used their profits to go to Cancun. But the money is half the fun. Jenkins points out, "It definitely beats working at Thayer."

Asian Studies major Charles Wheelan plans to travel aroundthe world as a freelance journalist after he graduates in June.Last year he spent a semester as an intern with a dailynewspaper in Kuwait. It was Charlie who first conceived thenotion of the Alpha Delta Mutual Fund.

Bargain Travel

Fraternity Bulls

Music Man

Cleaning Up

Into Africa

Safety in Numbers

Ballooning Business

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIs Academia Failing?

March 1988 By Jeffrey Hart '51 and Gregory S. Prince Jr. -

Feature

FeatureHe Knew what Played

March 1988 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

March 1988 By Sally Goggin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

March 1988 By Charles D. Vernon -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

March 1988 By Kenneth M. Johnson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

March 1988 By Monk Larson

Charles Wheelan ’88

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBEYOND ME

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Comes NEXT

JUNE 1998 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

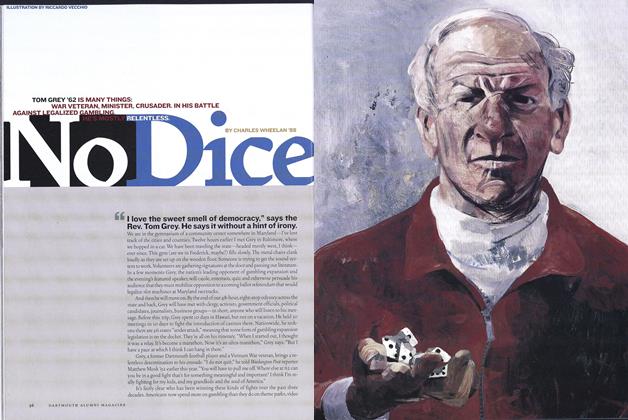

FeatureNo Dice

July/Aug 2003 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONLive Free or Die?

Jan/Feb 2009 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleReel Economics

September | October 2013 By Charles Wheelan ’88