As the College assumes the trappings of a university, how does it balance the budget?

ANYONE WHO has ever heard of the place will tell you that Dartmouth is a rich school. You can walk through the campus and see it for yourself. The buildings glow with the patina of meticulous care. The museum, arts center, sports facilities, library, and even the student body seem gilded with an unblemished perfection only possible with copious amounts of money well spent.

Indeed, like water joining itself, funds seem to flow into the school in a steady generous stream. The $17,106 tuition this year is one of the highest in the country and more than half the enrolled student body of 5,132 is able to pay it without any offsetting help from Dartmouth. The school's endowment stands at roughly half a billion dollars. And the supportiveness of the College's alumni is legend.

This is not to say that the school is in danger of imminent collapse. For the most part its lavish resources, manifold programs, and embossed reputation will continue to perpetuate themselves, at least for the time being. But economic forces both within and beyond Dartmouth's control are causing changes and necessitating decisions that, regardless of the direction taken, may significantly affect the school's identity in the years to come.

What has all this to do with the College budget? A great deal. An institution's annual budget is like a core sample—a (literally) penetrating view of a small section of territory that accurately reflects the nature of the whole. How much money is available and where does it come from? Where does it go, and who decides? These simple questions ultimately define the condition of the body academic.

The College's budget process also allows a look at a much larger spherethe increasingly shaky financial foundation of higher learning. In recent years, educational costs at virtually all colleges have far outpaced the general inflation rate. The particular goods and services purchased by academia, especially labor, are at the high-priced end of the scale. Students are demanding an ever-broader array of services, from state-of-the-art sports centers to art museums to nutritional counseling. Faculty members are no longer content to be classed among the honorable poor. And public subsidies are down.

Colleges and universities can't increase their cash flow by issuing stock or upping production. What they can do is raise tuition, and so they have precipitously. (At Dartmouth, tuition has virtually doubled since 1981.) This rise in the price of admission has set off a national political debate led by U.S. Secretary of Education William Bennett, who has repeatedly charged academic institutions with greed and irresponsibility. Thus the formulation of Dartmouth's fiscal 'B9 budget is taking place within a double set of constraints as college costs rise and public pressure to contain college charges increases.

It is important to set some ground rules here. This article is being written in late February—weeks before the final budget is scheduled to be presented to the Board of Trustees. The focus here is not on the figures, which may be old news (or wrong news) by the time the piece gets read, but on the process by which Dartmouth's budget is determined. The intent is to shed some light on the way in which the budget both establishes and reflects the philosophies and priorities that shape the place.

On April 10, 1987, the Dartmouth Trustees approved an operating bud- get of $181,656,000 for the 1988 fiscal year beginning July 1, 1987. Of this amount, $127,494,000 was allocated to the undergraduate program (and the small graduate program in arts and sciences) upon which this article focuses; the rest constitutes the three professional-school budgets, which are determined separately and have only an indirect effect on the undergraduate financial picture.

Almost as soon as the vote was in, Edwin Johnson, director of financial services and associate treasurer of the College, started work on the budget for fiscal '89.

Win Johnson is modest, softspoken, and fearsomely clearheaded and precise. A Dartmouth graduate (class of 1967) with a Wharton MBA, he wears Wellington boots with his well-tailored suits, and considers himself a citizen of the rural Upper Valley rather than the tightknit Hanover-based Dartmouth community.

If the person who controls the technology controls the game, then Johnson is the key player in the budgetary process, for it is his day-to-day labor that transforms ideas and priorities into working numbers, and his recommendations based on those numbers that drive the process forward. He is so deeply immersed in the Dartmouth fiscal plan that he thinks in thousands and millions and has trouble doing his family budget at home.

He was eager to get started on fiscal '89 because this year would be the test of a new and, he hoped, improved way of doing things—one that would allow the senior officers the opportunity to grapple with core problems earlier in the game. In the past the budget had been built from the ground up, involving detailed requests by faculty and administrators without a clear sense of what the College could afford. For the first time, Johnson was charged with working from the top down.

The concept is simple. Start with the fiscal '88 budget. Work with the budget officers from key areas within the College to determine the general outline of program demands. Assume reasonable inflation factors for items such as anticipated revenues, taxes, insurance, fuel costs, and—yes—tuition. Plug in known and unavoidable one-time costs. And add it all up.

The gap is the key figure in the budget process; closing it the focus of all deliberations. Determining this figure early on allows time for the development of thoughtful, creative fiscal strategies based on policy considerations rather than expediency. At least in theory. This year would be the test.

A copy of Johnson's model is taped to his office wall for ready referencerow upon row of figures stretching ten feet long. It is this document rather than detailed lists of needs from below that is now the point of departure for all budgetary debate.

If ever thoughtful, creative strategies were needed, it is in fiscal '89. The steep increase in overall costs has made it harder and harder simply to maintain ongoing programs. As a result, many areas throughout the College have been limited in the past few budget cycles to inflationary, or even sub-inflationary, increases. After several years of belt tightening there is little slack left, and the strain is beginning to show.

• Professor Bruce Pipes, associate dean of the faculty for the sciences, says that in the current year the discretionary increase in his area, excluding salaries, was held to two percent. Given the high cost of scientific materials, he says, this amounts in real dollars to an eight-percent cut.

• Professor Roger Masters, chair of the Government Department, complains that some courses in the department are oversubscribed by as many as 30 students. There is no money available for additional faculty, so he has had to turn students away. "That has never happened before," he says.

• "This year, for the first time," says Professor Faith Dunne, chair of the Education Department, "I've had to turn down perfectly reasonable requests from faculty that are directly related to the center of our interests"—a program series, for example, that would have enabled members of the department to meet regularly with teachers in the local schools.

The College's ability to respond to these demands is limited by constraints —both external and internalon the revenue side. Externally there is the public resistance to increased tuition and also the fallout from the stock market crash—a restriction in the extraordinary flow of endowment income enjoyed in the previous two bull market years.

Internally, there is the $1 million shortfall partially carried over from fiscal 'BB caused by an underestimation in off-campus enrollments; as well as the College's endowment spending cap—a complex formula that limits the amount of endowment income that can be spent in a given year so as to moderate the effect of market fluctuations over the long haul.

Put it all together and it becomes clear that fiscal 'B9 will be, at best, a difficult year.

The memo contained a stern warning: "The conclusions we have drawn from this exercise are not ones you will welcome .... The FY 89 budget cycle will be no easier than those of the recent past, and in fact each year may just get more difficult until we deal with the fundamental issues of institutional priority and our ability to reallocate old resources [read: eliminate low-priority programs] as well as consume new ones."

Thus, Johnson set the agenda for the budgetary process: establish philosophic priorities, and review all programs with an eye toward cutting old ones as new ones are added.

The memo was specifically directed to the president and those senior officers who make the ultimate budgetary decisions. They are: Vice President of Finance and Treasurer Robert Field '43, Vice President of Development and Alumni Affairs Warren Hance '55, Dean of the Faculty Dwight Lahr, Dean of the College Edward Shanahan, Acting Provost John Strohbehn, and Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid A1 Quirk '49.

Each member of the group has his own set of priorities by virtue of the area he represents. It is the working out of these competing interests, in a series of weekly meetings, that shapes the final budget document to be prsented to the Trustees in April. At each meeting, priorities are considered and options discussed, and Johnson leaves with new figures to plug into his model.

Personnel Director William Geraghty, who represents the interests of the College's 1,500 administrative employees, occasionally attends. So does President James O. Freedman, whose participation in the process is less "hands-on" than was that of his predecessor. "McLaughlin took a more active role in selecting areas for cuts, whereas Freedman lets the senior officers decide; he is a consensus builder," says Lahr.

Indeed, consensus is the name of the game for all the players, according to their own testimony. To a man, they emphasize that the winnowing process is collegial, with each keeping the best interests of the College as a whole in mind; but hints emerge that there is a fair amount of (civilized) turf-fighting as well. "People become very protective of their own programs, and it can be difficult to reach resolution," says Robert Griesemer, Lahr's budget officer.

"There is some gamesmanship/'acknowledges Shanahan. "Someone will say that he has no choice but to cut six people and later you find out he's just cut back on publications."

Professor Hoyt Alverson, former chair of the Anthropology Department, views the process from the unique perspective of his own particular discipline: "It's fairly intense tribal warfare. The effectiveness of a head determines how much you get."

Regardless of the conflict inherent in the process, a collective decision was made early on that three areas should be given top priority—financial aid, library acquisitions, and compensation. "These three were so clearly recognizable as needs that they were priorities almost before we started talking about the budget," says Hance.

formula), Dartmouth will make up the difference between that amount and the total tuition, either by deferred loan or outright gift.

In fiscal '88, this guarantee costs the College $11 million—up 13 percent from the previous year. For fiscal '89, Johnson factored a 15-percent increase into the model—more than twice the projected increase for tuition, because of a larger population of qualifying students and because federal and other support for college students is down.

"We have a commitment to ourselves and to society to have a diverse student body," says Hoisington, noting a "slow but steady erosion" in the number of lower-income students able to consider attending an institution that charges almost as much per year ($17,000-plus) as the national median take-home income for a family of four ($22,000).

Perhaps because this commitment is felt equally throughout all areas of the College, financial aid is the priority among priorities—the item most insulated from cuts of any kind. Whatever is requested in this department is likely to be provided in full.

Library acquisitions is another priority area with strong across-the-board support, including that of President Freedman. "Libraries are the heart of an academic institution," he said in a recent interview. "If you fail to sustain the quality for a year or two, it's impossible to make that up."

The situation Freedman describes is in danger of becoming a reality. Last fall, when asked to report any unusual expenses anticipated in the coming year, the libraries sounded an alarm. The cost of serial publications (research journals and other multivolume materials) —especially those published abroad—was skyrocketing. Fueled in part by the declining dollar and in part by simple greed, the prices of such publications as Leukemia Research, Plant Molecular Biology, and Universities Quarterly had more than doubled since 1982.

The College subscribes to some 19,000 serial publications, at a cost of approximately $1.6 million in fiscal '88. This year, College Librarian Margaret Otto says she needs a 25-percent increase in this line item simply to stay even. If she doesn't get it, some subscriptions will have to be dropped. "Cuts would be very detrimental to us because we're already very selective," she says.

Otto stresses that even if she receives every penny of her request, the money will in no way cover the additional subscriptions needed to support new programs such as Hebrew and Arabic studies and a variety of international exchange arrangements with Japan and the Soviet Union.

She is pleased that the library is a priority item, but, with a skepticism bred of long experience, she isn't counting on anything yet. "It may be a priority, but how much of a priority? I want to see it in writing," she says with a smile.

Her instincts are on target. Subscriptions to serial publications, despite priority status, will probably not receive the full protection from cuts accorded financial aid. "We wanted to give the library enough to stay even," said Strohbehn in late January, "but we won't be able to do it." His domain includes the Hood Museum, Hopkins Center, and the professional schools as well as the library, and he must balance the interests of all.

Compensation, the last of the three top priorities, is by far the most controversial. In the current year, this item weighs in at $19,600,000 for faculty alone—not enough to avert what many regard as an emergency situation.

Faculty salaries and benefits at Dartmouth have historically lagged behind those at peer institutions. Several years ago this trend, coupled with a decrease in the number of Ph.D.'s seeking academic positions, led to some hiring failures. Top candidates were opting for more generous terms elsewhere and several of Dartmouth's most valued faculty members were raided by other, more openhanded institutions.

In response, Faculty Dean Lahr asked for an emergency infusion of funds for junior faculty and then embarked on an ambitious three-year plan to raise all salaries to the mean level of pay at a group of selected peer colleges and universities, including Princeton, Columbia, Yale, and Brown. During the first two years, the emphasis was placed on upgrading entry-level positions. This year the press is on to equalize upper-level salaries that, in some cases, have fallen below those now paid to new assistant professors.

The Committee on the Economic Status of Faculty (CESF), a faculty advisory committee to the president, has stated that an increase of 18 percent is necessary to bring upper-level salaries into line with the competition. Lahr, citing differences among peer institutions in such matters as relative age and rank of faculty that could account for a sizable portion of the compensation gap, is thinking more along the lines of a nine-percent increase.

But, at $196,000 per percentage point, even a nine-percent increase eats up a large portion of the $6 million increase in revenues Johnson had projected.

Add to this a piggybacked increase for administrative and service employees ("If you have a top-rate faculty you want to have a top-rate staff to support them," says Griesemer, Lahr's assistant) and you effectively preclude any other initiatives, says Treasurer Field. "The three-year faculty compensation plan places a strain on the system," he says.

Those whose operations are not faculty-intensive resent this burden. "The budget has been pared significantly over the last three years," notes Dean Shanahan. "If there was fat, it's just about gone. Now individuals will see some of the effects of their efforts to increase compensation."

Freedman felt this exercise would foster a sense of "alertness"—a habit of constant review to clear away the deadwood. "In the budget process, it's important not to accept the idea that you should continue as before," he said. He also wanted to establish a potential funding source for new initiatives. "We started off with great hope that we could create a pool of resources for the exciting things we wanted to do," he said.

But, as Dean Lahr puts it, "A slush fund only works if the budget balances at the beginning of the year." Once it became apparent that this was not to be the case, he says, "the whole thing fell apart." But not quite. Those lowpriority lists, originally an exercise in contemplation of new initiatives, have now become the blueprint for mandatory cuts.

By the beginning of February, the gap had been reduced to just over $1 million from a high of $2.8. This had been accomplished through several rounds of cuts as well as upward justments in anticipated revenue—including tuition.

At this point, the senior officers agreed to a final step to close the gap: Johnson identified for each group member an "assignment"—a dollar amount that he would have to cut from his area before the next meeting, based on the proportion of the total budget that was under his control. The exception was Lahr. After some wrangling, it was agreed that faculty compensation would be deducted off the top before his percentage was figured. The others' target cuts ranged from $100,000 to 280,000. Lahr's came in at $45,000.

With this last push, the hope of policy-based strategies disappeared. "This is now a short-term balancing process, not long-term planning," Johnson admits. "We've wrestled with the implications of reducing program budgets and that's the way we'll go. We'll just have to tell that to the Trustees."

Now, with their feet to the fire for real, the senior officers contemplated the final, hardest choices. Among the options they considered: postponing needed computerization programs at the library and the museum, closing down the Dick's House infirmary during the underpopulated summer term, reducing development mailings (thus risking a possible reduction in gifts), curtailing the hours of the Career and Employment Services and Residential Life offices, limiting performances at the Hop, charging admission to the Hood, eliminating the freshman advisors program, and even letting people go.

These are not the choices that a rich school should have to make. Field bluntly resolves this conundrum. "Dartmouth isn't rich," he says. To be rich, he explains, means to have limitless resources and these resources are not there.

Certainly no one expects Dartmouth —or any other entity on this Earth—to have limitless resources. The question here is why Dartmouth, with its national reputation for affluence, does not appear to have resources sufficient to support its basic programs as well as do its peers.

"It's been a real strain to increase compensation—and just when we thought we'd done it, the other schools did as well or better," says Professor John Menge, chair of the Economics Department. In other words, those schools were able to tap into resources that apparently are not available at Dartmouth.

In hope of discovering why this is the case, the Council on Budgets and Priorities—an advisory group chaired by Menge that was established in the mid-'70s to introduce long-term considerations into the budget processcommissioned the consulting firm of Cambridge Associates to prepare a comparative fiscal profile of the school.

The first Cambridge Report is just out. It appears to indicate that the sources of Dartmouth's budgetary strains run deep and are intrinsi callyre lated to the nature of the school.

The consultants compared Dartmouth's financial structure in a variety of ways with those of six other schools—Princeton, Brown, Williams, Wesleyan, and the Universities of Rochester and Pennsylvania. Although each school's budget is idiosyncratic and difficult to compare accurately with that of the other schools, the firm reached the tentative conclusion that Dartmouth in its present form may have difficulty supporting its university-scale array of programs.

As the analysts stated in the report's summary: "One of the central dilemmas facing Dartmouth [is that] by mission it chooses to be a university, but its capitalization [endowment] and revenue structure are suited more to a college. While this is by no means to suggest that its current capitalization and revenue profile cannot support a university, they are unlikely to be able to do so comfortably."

hired on the basis of research interests and the ability to get the publicly funded grants that are needed to support such an enterprise?

Menge, for one, believes that the shift in emphasis—and identity—is already in progress. "We have engineering, business, and medical schools, a performing arts center, a museum. We are a university, but the problem is we're not a very large university. Maybe there are those who love it, but as a university, it's too small to be efficient."

Field, on the other hand, is among those who advocate going slow. "What Dartmouth does best is undergraduate education. It's preeminent in that area—one of the best in the country. If we change, for whatever reason, we have to be very careful to retain that, or else we'll be just another institution."

For others, Johnson included, a choice must be made, whichever way it goes. "We can't afford to do it all on a first-class ticket," he says. "We can't afford academic support facilities like the Hood, the Hop, and Kiewit, or faculty salaries equal to salaries at universities, when we don't have the grant support that universities have. We have to either cut back or expand revenues."

It is not a matter of total resources, he believes, but of how those resources are allocated. "Dartmouth's resources are, I maintain, extraordinary," he says. "The fundamental question is not what we've got but how we spend it. We have to define our mission and, once this is done, work carefully to allocate the means to support it. It will be essential to make difficult choices. This is part of playing the game."

The consensus seems to be that a move in either direction could be justified and would make financial sense. What matters is that a conscious and conscientious decision be made. If this does not happen soon, some officials fear evermore restrictive budgets, with intensified competition for available funds. And Dartmouth may find itself changing by increment rather than by design.

Like a conductor with a complex score,Financial Services Director EdwinJohnson '67 uses ten-foot spreadsheets topull the budget together. The process getsmore difficult each year, he says.

One Of The Costliest SchoolsIn The Country...TUITION ROOM TOTALAND FEES AND BOARD COST 1. Bennington College 14,850 3,140 17,990 2. Sarah Lawrence 12,376 5,065 17,441 3. Barnard 12,104 5,192 17,296 4. U. of Chicago 12,460 4,730 17,190 5. Columbia U./College 12,170 4,950 17,120 6. Harvard / Radcliffe 12.890 4,210 17,100 7. Dartmouth College 12,474 4,600 17,074 8. Brown 12,960 4,075 17,035 9. Tufts 12,088 4,940 17,028 10. Yale 12,120 4,900 17,020 Dartmouth 1987-88 tuition ranks as one of the highest of the elite schools. Source: College BoardChart: Anton Anderson '89

Deborah Solomon is a writer living in Newbury, Vermont. She has been a lawyer, hasworked as a producer and reporter for publictelevision, and most recently has served aseditorial director of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center's Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFather Bill's Answers

April 1988 By Benjamin Hart ’81 -

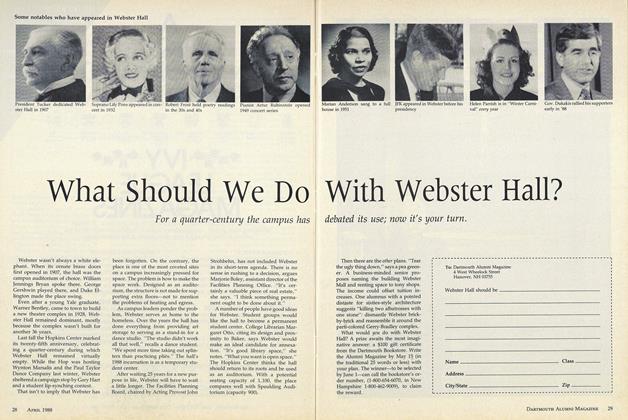

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhat Should We Do With Webster Hall?

April 1988 -

Article

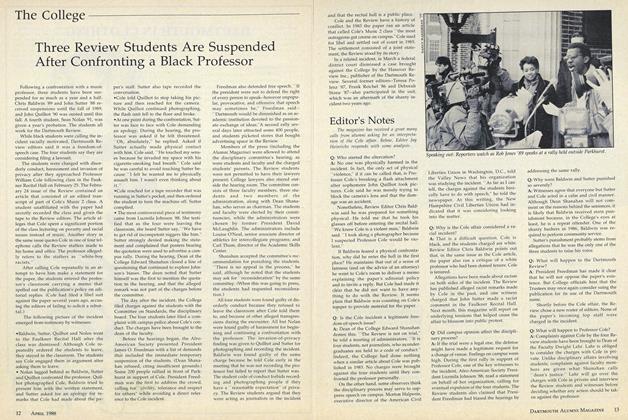

ArticleThree Review Students Are Suspended After Confronting a Black Professor

April 1988 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editorthe magazine has received a great many calls from alumni asking for an interpretation of the Cole affair.

April 1988 -

Article

ArticleThree Minutes and One Second

April 1988 -

Sports

SportsBaseball ’88: Opting for Optimism

April 1988

Deborah Solomon

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1956 -

Feature

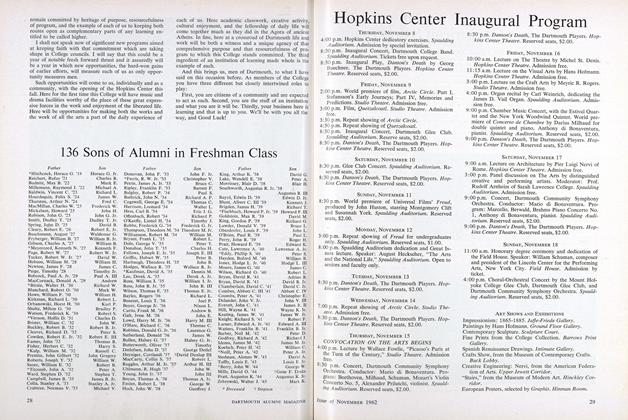

FeatureHopkins Center Inaugural Program

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

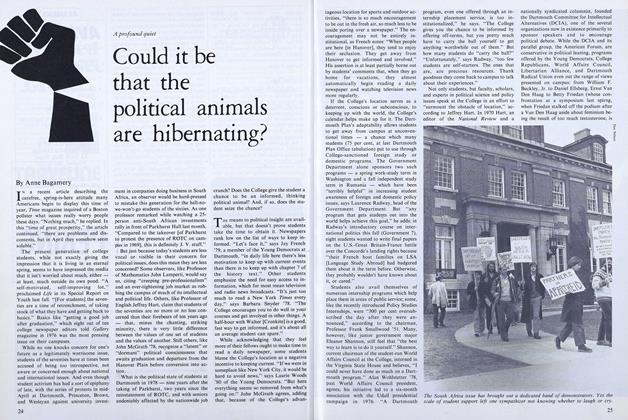

FeatureCould it be that the political animals are hibernating?

MAY 1978 By Anne Bagamery -

Feature

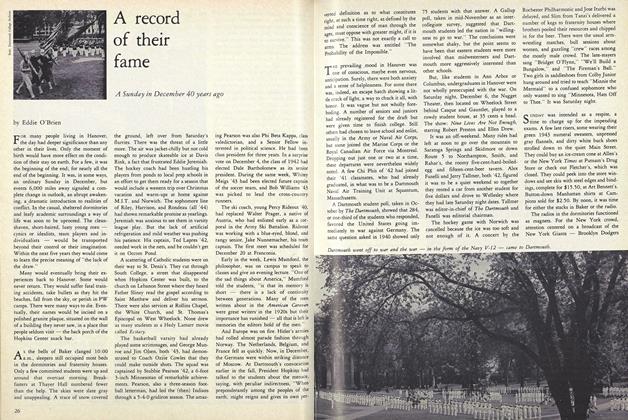

FeatureA record of their fame

NOVEMBER 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

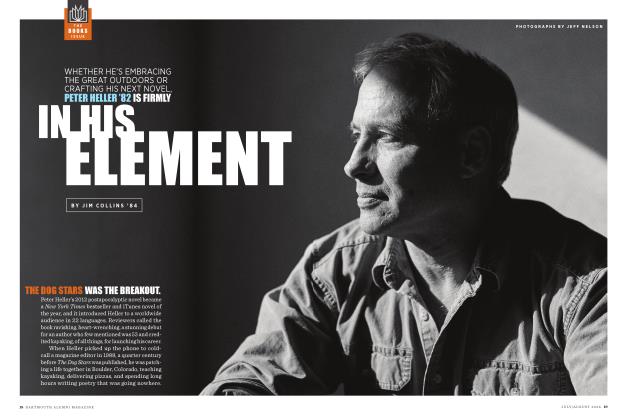

FeatureIn His Element

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureStar Wars: 'Peace Shield' or Prelude to a New Arms Race?

MAY 1986 By Peter Mandel