Dartmouth's departing priest leaves a legacy of moral certainty.

IREMEMBER MY first conversation with Monsignor William Nolan, who prefers to be called "Father Bill." It was my freshman year, and I was studying for midterms late one night at the Aquinas House's Newman Library. While taking a break I happened to walk by the monsignor's office. He was working late also and invited me in. We talked about a variety of subjects: people, courses, campus life. I was a nominal Catholic at the time and had not given the spiritual side of my life much thought—which no doubt was obvious.

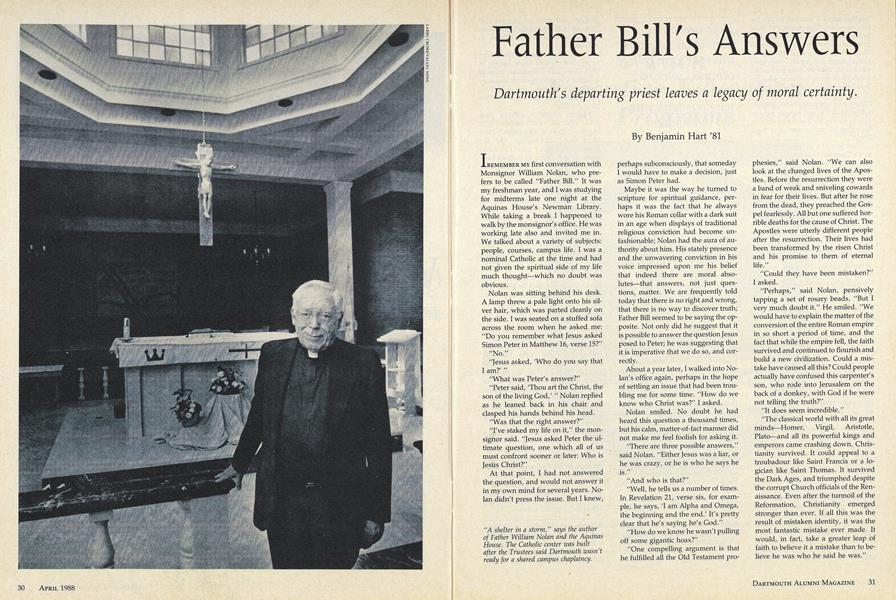

Nolan was sitting behind his desk. A lamp threw a pale light onto his silver hair, which was parted cleanly on the side. I was seated on a stuffed sofa across the room when he asked me: "Do you remember what Jesus asked Simon Peter in Matthew 16, verse 15?"

"No."

"Jesus asked, 'Who do you say that I am?' "

"What was Peter's answer?"

"Peter said, 'Thou art the Christ, the son of the living God,' " Nolan replied as he leaned back in his chair and clasped his hands behind his head.

"Was that the right answer?"

"I've staked my life on it," the monsignor said. "Jesus asked Peter the ultimate question, one which all of us must confront sooner or later: Who is Jesus Christ?"

At that point, I had not answered the question, and would not answer it in my own mind for several years. Nolan didn't press the issue. But I knew, perhaps subconsciously, that someday I would have to make a decision, just as Simon Peter had.

Maybe it was the way he turned to scripture for spiritual guidance, perhaps it was the fact that he always wore his Roman collar with a dark suit in an age when displays of traditional religious conviction had become unfashionable; Nolan had the aura of authority about him. His stately presence and the unwavering conviction in his voice impressed upon me his belief that indeed there are moral absolutes —that answers, not just questions, matter. We are frequently told today that there is no right and wrong, that there is no way to discover truth; Father Bill seemed to be saying the opposite. Not only did he suggest that it is possible to answer the question Jesus posed to Peter; he was suggesting that it is imperative that we do so, and correctly.

Nolan smiled. No doubt he had heard this question a thousand times, but his calm, matter-of-fact manner did not make me feel foolish for asking it.

"There are three possible answers," said Nolan. "Either Jesus was a liar, or he was crazy, or he is who he says he is."

"And who is that?"

"Well, he tells us a number of times. In Revelation 21, verse six, for example, he says, 'I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end.' It's pretty clear that he's saying he's God."

"How do we know he wasn't pulling off some gigantic hoax?"

"One compelling argument is that he fulfilled all the Old Testament prophesies," said Nolan. "We can also look at the changed lives of the Apostles. Before the resurrection they were a band of weak and sniveling cowards in fear for their lives. But after he rose from the dead, they preached the Gospel fearlessly. All but one suffered horrible deaths for the cause of Christ. The Apostles were utterly different people after the resurrection. Their lives had been transformed by the risen Christ and his promise to them of eternal life."

"Could they have been mistaken?" I asked.

"Perhaps," said Nolan, pensively tapping a set of rosary beads. "But I very much doubt it." He smiled. "We would have to explain the matter of the conversion of the entire Roman empire in so short a period of time, and the fact that while the empire fell, the faith survived and continued to flourish and build a new civilization. Could a mistake have caused all this? Could people actually have confused this carpenter's son, who rode into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey, with God if he were not telling the truth?"

"It does seem incredible."

"The classical world with all its great minds—Homer, Virgil, Aristotle, Plato—and all its powerful kings and emperors came crashing down. Christianity survived. It could appeal to a troubadour like Saint Francis or a logician like Saint Thomas. It survived the Dark Ages, and triumphed despite the corrupt Church officials of the Renaissance. Even after the turmoil of the Reformation, Christianity emerged stronger than ever. If all this was the result of mistaken identity, it was the most fantastic mistake ever made. It would, in fact, take a greater leap of faith to believe it a mistake than to believe he was who he said he was."

I had taken a number of religion courses where Christianity had been treated as merely some sort of anthropological phenomenon, interesting for historical background but of little practical importance to our daily lives. Here was an individual who was unusual for a college campus, someone who believed that religious faith was not out of date. Moreover, he did not think Christianity was just another religion, similar to all the rest, equally right or equally wrong. He had in fact devoted his entire life to the service of Jesus Christ.

Nolan gained a strong commitment to the Christian faith early in life. But he also enjoyed the things other boys enjoyed. He lettered in hockey at Boston Latin School, and was elected president of the class of 1935. He went on to earn a bachelor of arts degree from St. Mary's College in northeastern Pennsylvania. He then entered Mount St. Alphonsus Seminary in Esopus, New York, where he studied the Scriptures, philosophy, Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and canon law, and earned a master's in theology. In 1944 he was ordained a priest. For three years he taught at the seminary at St. Mary's College, after which he enrolled in the Preacher's Institute at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., where he earned a master's in education. He spent several years travelling up and down the East Coast from Philadelphia to Maine doing missionary work.

One of Father Bill's greatest strengths has been his ability to carry on a powerful ministry without offending those of other denominations and faiths. He came to Hanover in 1950, when there was still a good deal of anti-Catholic feeling in America, the Dartmouth campus being no exception. As assistant chaplain at Hanover's St. Denis Church, he was charged with ministering to Dartmouth's 200 Catholic students. "There was virtually no organized Catholic presence on the campus when I first arrived," recalls Nolan. "It was clear to me that a Catholic ministry was needed."

But when Nolan asked if he could hold masses in Rollins Chapel, he was refused. Undiscouraged, Nolan persevered, quietly. He was eventually permitted to hold question-and-answer forums in Rollins Chapel, so long as a knowledgeable Protestant was present to answer questions as well. Usually, Father Bill's counterpart at the sessions was Professor Fred Berthold, then director of the Tucker Foundation. Berthold is still active on campus as a professor in the religion department. "Fred contributed enormously to reducing tensions on campus between Catholics and Protestants/' Nolan remembers.

In 1953, Bishop Matthew Brady of Manchester, New Hampshire, appointed Nolan as a full-time chaplain for Dartmouth's Catholic undergraduates. The bishop bought a house for the students on 13 Choate Road. But for the next seven years there was uncertainty about whether there would, or should, be a Catholic chapel on campus. When President John Sloan Dickey appointed a committee to recommend improvements on the moral life of the College, the committee suggested that the campus chaplaincy be expanded to include a Catholic, speifically Nolan, who had become popular with the students. The Trustees refused, saying this was not the time. Nolan held daily masses in a makeshift basement chapel in the Choate Road House, and continued to send the students across town to St. Denis Church for Sunday worship.

In 1958, Father Bill met with Cardinal Gushing, who saw that the facilities were inadequate for a campus ministry. He presented Nolan with $50,000 for construction of a genuine sanctuary suitable for Sunday masses. Aquinas House was consecrated on April 29, 1962.

News of Father Nolan's Catholic student center caused something of an uproar—not so much within Dartmouth's ranks as elsewhere around the Ivy League. One Princeton professor circulated a pamphlet titled "An Open Letter to John Sloan Dickey." The circular began, "Wake up John Dickey!" and went on to warn that there was a Roman Catholic plot afoot to take over the major colleges in America.

There's no question that the College appreciates Nolan's work today. In 1973 Dartmouth's Board of Trustees awarded the monsignor an honorary doctorate of divinity, and in 1978 he was made an honorary member of the class of 1953.

Aquinas House is stronger than ever. "What you've accomplished here is nothing short of miraculous," President David McLaughlin told the beaming monsignor after Christmas mass one year. Some 40 students have chosen vocations in the priesthood since Aquinas House first opened its doors. Masses are held daily. In addition to the chapel, the center has a library, two study rooms, a television room, ping-pong, a pool table and a kitchen, all supported by donations from parents, alumni and "Friends of Father Bill." There are also potluck dinners, seminars and retreats. Every Monday evening Nolan held forums where students could ask questions about their faith.

"Aquinas House is a home away from home for many of the kids," says Nolan. "Our hope was to assist in the spiritual development of all the students—Catholics, Protestants, Jews, or whoever wanted guidance."

Last May, Monsignor William Nolan retired from his pastoral duties at Dartmouth at age 71. He has been succeeded by Father John McHugh, assistant chaplain under Nolan for the past two years. McHugh has an unenviable task ahead. A number of students wept at Father Bill's retirement party. One said that for her, Nolan's departure "will create a void that is unfillable." Dartmouth "cannot afford to lose this man," said another.

For these students, Nolan was a shelter in the midst of a storm. College is a turbulent period. Students, in addition to being apart from their families (perhaps for the first time), are taught in the classroom to be skeptical of longheld beliefs, always to "ask questions." But asking questions is easy. For 37 years as the Catholic chaplain, Father Bill provided answers.

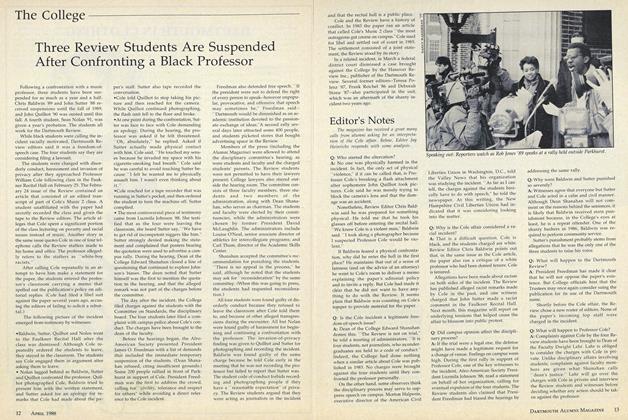

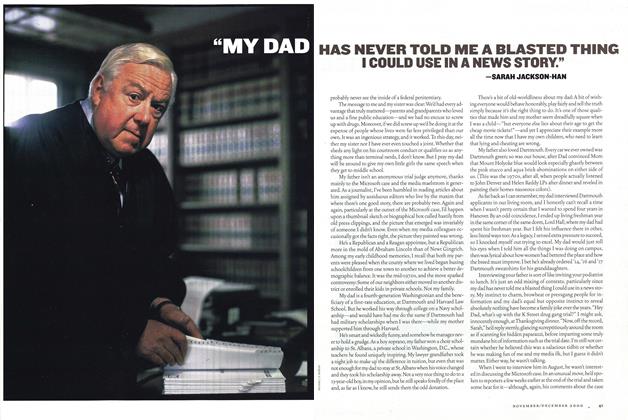

"A shelter in a storm," says the authorof Father William Nolan and the AquinasHouse. The Catholic center was builtafter the Trustees said Dartmouth wasn'tready for a shared campus chaplaincy.

Here was anindividual who wasunusual for a collegecampus, someonewho believed thatreligious faith wasnot out of date.

Benjamin Hart '81, author of "PoisonedIvy," is director of lectures and seminarsat the Heritage Foundation in Washington,D.C. His third book, "Faith and Freedom,"will be published this year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

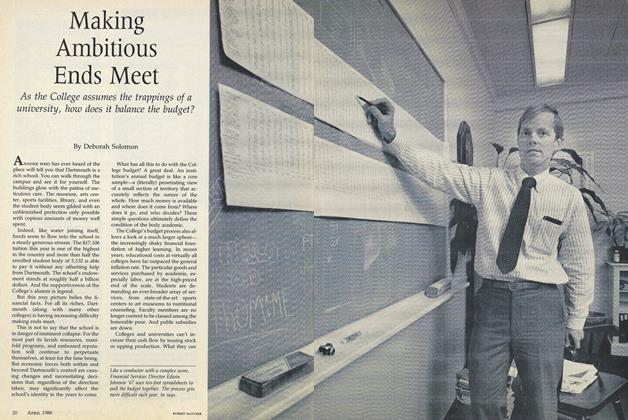

FeatureMaking Ambitious Ends Meet

April 1988 By Deborah Solomon -

Cover Story

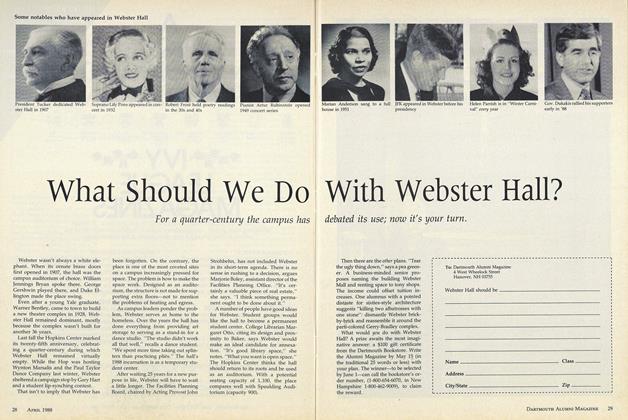

Cover StoryWhat Should We Do With Webster Hall?

April 1988 -

Article

ArticleThree Review Students Are Suspended After Confronting a Black Professor

April 1988 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editorthe magazine has received a great many calls from alumni asking for an interpretation of the Cole affair.

April 1988 -

Article

ArticleThree Minutes and One Second

April 1988 -

Sports

SportsBaseball ’88: Opting for Optimism

April 1988

Features

-

Feature

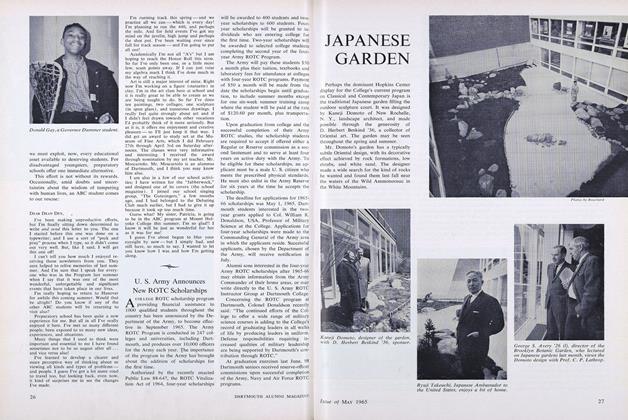

FeatureJAPANESE GARDEN

MAY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2006 By Gar Waterman '78 -

Feature

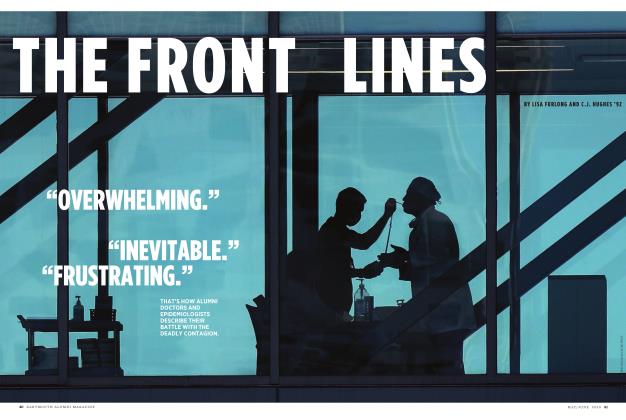

FeatureThe Front Lines

MAY | JUNE 2020 By LISA FURLONG, C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

Nov/Dec 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham