UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

One has to doubt the luck of a person who emerges safely from riots in Lhasa, Tibet, only to become trapped in a bus with 40 other foreigners on a lonely and bitterly cold mountain pass. When this same person lives on minimal food (one-halfcup of moistened barley flour per day) and water (melted snow) for seven days, and then walks out 60 miles through dangerous terrain to safety, one would expect that conditions would improve. But when three weeks later the adventurer is attacked and nearly killed by an Indian rhinoceros while trekking through the jungle on an ostensibly safe guided tour, one begins to wonder about this person.

I really don't blame them, since I'm that person. But the story doesn't end there. One of the stranger experiences came afterward, when I witnessed the reactions of people in my midwestern hometown and at Dartmouth. The contrasts in attitudes between those two places helped me understand why I love this college so much.

The first reactions were in my native Kansas. "I don't really consider that my luck was that bad," I said to a Kansas City television reporter who asked why I thought my luck had failed. "I would do it all over again ... except for the rhinoceros. I would not want to be attacked by a rhinoceros again." He looked at me incredulously, as though he half expected me to reveal regret.

When the news reached Lawrence, Kansas, last October that I had trekked safely 60 miles out of the pass to Kathmandu, countless people stopped my father on the street, expecting that he had demanded my immediate return. "So she'll be coming right home?" they all asked sympathetically, sure that he had finally realized his mistake in allowing his 19-year-old daughter to stray so far from the nest. They shrugged their shoulders in dismay when my father replied that my trip would continue as planned.

My friends at Dartmouth, on the other hand, were far from discouraged by my bad luck. They are perfectly aware that Asia is not inevitably a doorway to disaster. When I returned to school last winter, expecting the same reactions of horror and anguished sympathy that I had witnessed in Kansas, I was pleasantly surprised. Instead of viewing my debacles as a lesson in the merits of conservative conduct, they saw them almost (but not quite) as enviable experiences. "I took the same trip she did," someone told my roommate in exaggerated annoyance. "Why don't things like that happen to me?"

Dartmouth students viewed what happened to me in Tibet and Nepal in an entirely different light from the residents of my hometown. The prevailing attitude here is one of appreciation for challenge and adventure. A College administrator who understands this saw me on the "Today" show. "That has to be a Dartmouth student," he said, turning to his wife.

During my time in Asia I had forgotten the sense of adventure, vitality and humor that pervades the Dartmouth campus. And coming back to the College and its tranquil surroundings, I'm better able to experience the repose as well as the spirit. The administrator was right-I could only have been a Dartmouth student.

Junior Emily Hill is a history major. Rhinoceroses, she says, are not part of her life plans.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

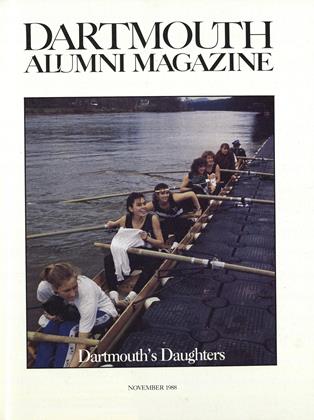

Cover StoryDaughters of Dartmouth

November 1988 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureGlory Days

November 1988 By Woody Klein '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Helplessness of a "Bureaucrat of Legendary Proportions"

November 1988 By Jonathan Cowan '87 -

Feature

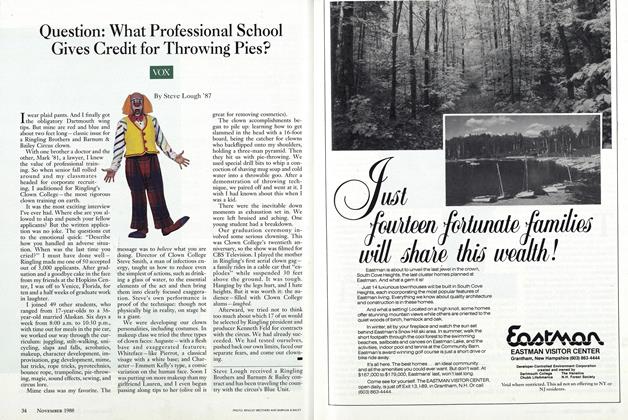

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

November 1988 By Steve Lough '87 -

Sports

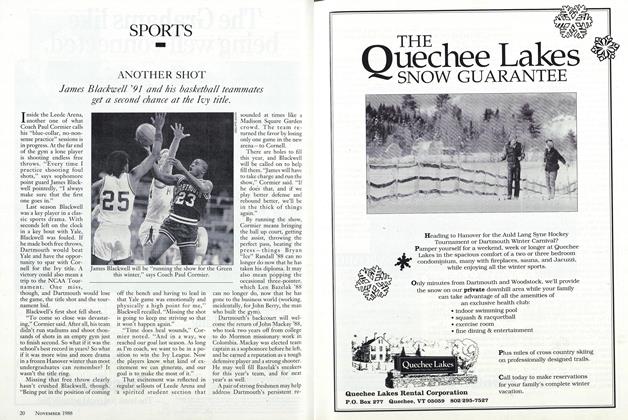

SportsANOTHER SHOT

November 1988 -

Article

ArticleSHOULD DARTMOUTH DIVEST?

November 1988

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe 1961 Alumni Awards

July 1961 -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

Sept/Oct 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Cover Story

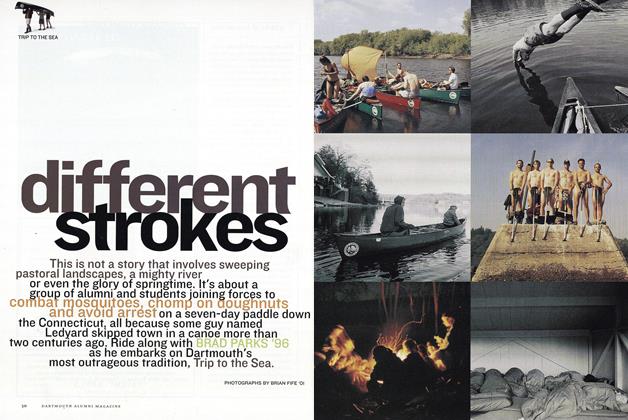

Cover StoryDifferent Strokes

May/June 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Feature

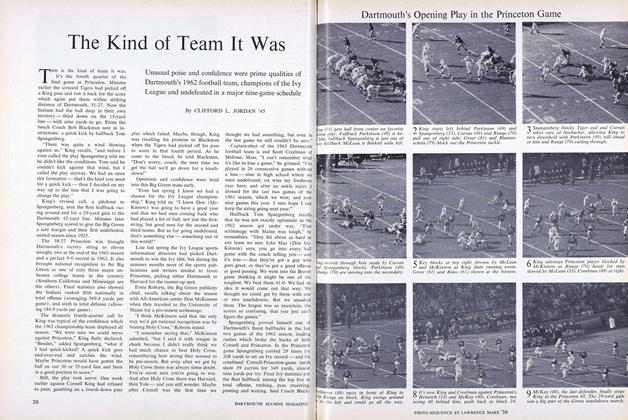

FeatureThe Kind of Team It Was

JANUARY 1963 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

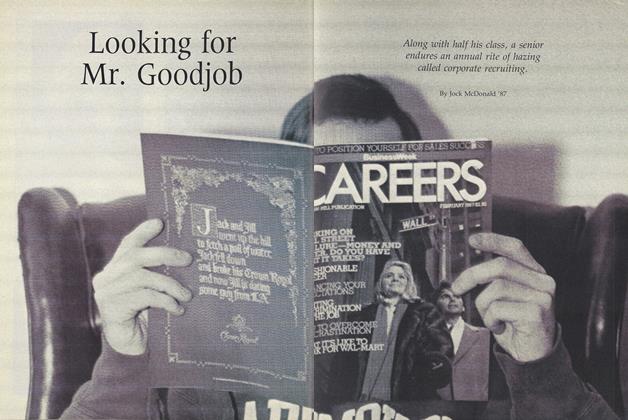

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

MAY • 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/Aug 2013 By Mark Brosseau ’98, Mark Brosseau ’98