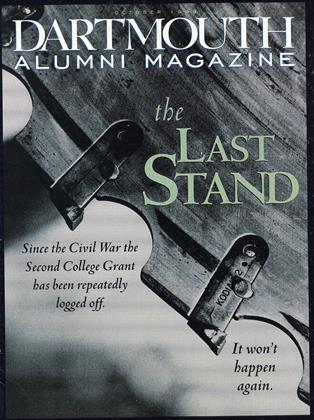

College forester Kevin Evans takes the long view of an abused resource, and plots the comeback of a troubled Northern Forest.

WITHMOONRISE two hours away, the Second College Grant tonight is a study in darkness. Blackest of all are the spruce and fir trees, sharp spires against the charcoal sky.

Three figures walk slowly down a grassy strip near the Swift Diamond River, state biologist John Lanier on point. Every 20 feet or so he turns on a powerful spotlight and sweeps the ground—front, right, left. In the shocking white light every twig and blade of grass stands out in sharp relief. Lanier flips a switch and all goes black again. They walk on. College forester Kevin Evans and wildlife technician Julie Wiles follow close behind, long-handled nets at the ready.

This is the team's third night out and they have yet to catch their quarry, the male woodcock. Chubby, famously elusive birds with absurdly long beaks, woodcocks roost at night in shrubby undergrowth and will not flush until absolutely nec essary. Wiles had learned that last night, when a bird took off right under her boot. Her wild swing with the net had caught only air.

If the trio catches a bird they'll collar it with a tiny radio transmitter. The signals will leave a wingprint, as it were, of where the woodcocks spend their time. Evans wants to know this. The three give up around midnight. Packing the gear away, Evans and Lanier banter about cutting trees. Lanier, the biologist, wants to see more of the forest cleared. Evans, the forester, isn't so sure.

"You mean you want a field here ?" "Yup. Think you can do that?" Evans smiles. "We'll see." He pulls off his headlamp and runs a hand through his straight brown hair. It's late, but he's in no rush. Deep in the Northern Forest, the three friends lean against a pickup truck and talk quietly about birds and trees and grass.

A slow-rising moon touches the woods with silver. Crickets and katydids sing in the alders. Evans stretches. "Well, I guess...."

In less than six hours the first log truck will thunder past the gate cabin. The team is staying on the Grant tonight, and those early rumblings will be their alarm clock.

THE WOODCOCK STUDY is part of a five-year, quarter-million-dollar science project underway at Dartmouth's Second College Grant, 27,000 acres of working timberland in far north-eastern New Hampshire. In addition to hunting woodcock, Wiles and Lanier are setting up 150 permanent monitoring plots where they will measure forest growth, wildlife comings and goings, and decomposition of leaves and downed and dead wood. Else where on the Grant Dartmouth biologists Matthew Ayres and Malcolm Strand are counting brook trout and measuring stream siltation. Biologists from the Audubon Society of New Hampshire are keeping watch over a peregrine falcon nest on Diamond Peaks.

This science is rigorous and credible, but it's not purely academic, and the Grant is not just some over-sized outdoor lab. It also is a place well laced with roads and trails and dotted with cabins. It is a place where freshmen orient and alumni reunite, where the comforting aroma of mothballs and wet wool can be as thick as blackflies in May. But before all this, before the College even had field biologists or an outing club, the Grant was a hard-working timberland. For a century and a half, its trees have been felled and sold to pay for scholarships and faculty salaries and landscaping on the Green. That's why the state gave the land to Dartmouth in the first place. Balancing these differentuses is the College forester's job.

Kevin Evans, who has been College forester since 1993, explains all this as he drives north on Dead Diamond Road to check out a new logging job. It's August. The Joe-pye weed has faded to a burnt pink. Golden rod is just coming on. In Loomis Valley in the heart of the Grant, Evans turns onto the raw dirt of a new logging road. A quarter-mile uphill, the road ends in a clearing filled with heavy equipment: culvert pipes, four-wheel-drive pickup trucks, fuel tanks, two massive tires lying on the ground. In the middle of the clearing a portable sawmill called a slasher is surrounded by logs, freshly cut and oozing in the morning light. The sweet smell of cut wood mixes with the dull stink of diesel.

Evans steps down from the truck and waves to Dennis Bovin, sitting high up in the cab of the slasher. Bovin works for Normand Jacques, the primary logging contractor on the Grant since 1987. Jacques's crew is led by a man who runs the fellerbuncher, a large machine that resembles a backhoe fitted with a huge hydraulic clamp and a cutting head. The feller crawls up to a tree, grips it with the clamp, cuts it with a circular blade, lays it down, and moves on. Two heavy-duty woods tractors called skidders follow the feller through the woods. The skidder operator cuts the small branches off with a chainsaw and wraps a cable around the trees to drag them to the yard.

From the cab of the slasher, Bovm grabs each log with a mechanical arm and runs it through a circular saw. The logs go into one of two piles. The smaller pile contains higher quality "sawlogs"; the larger pile is full of twisted, smaller, or forked logs designated as "pulpwood." Pulpwood from the Grant goes to paper makers Crown Vantage in Berlin and Mead Corp. in Rumford, Maine. Most of the softwood sawlogs (spruce, fir, hemlock, a bit of pine) go to a local sawmill. Hardwood sawlogs (birch, hard maple, beech, and ash) the most valuable products, get shipped to whichever mill is paying the most that week.

Evans nods approvingly as Bovin examines each log before dropping it on to the proper pile. Evans knows that a wrong choice—such as putting a hardwood sawlog in the pulp pile—can be a $500 mistake. He has planned every step in this timber harvest and this is the last critical decision: how to squeeze the most dollars out of every log.

Months before the loggers came in, Evans had laid out the truck road and supervised its construction. After marking the harvest area with orange ribbon, he'd walked the site with

state wildlife biologist Will Staats, who taped off stream buffers, special wildlife trees, vernal pools, and other ecological features. Evans and consulting forester Greg Ainsworth had then spent several sweaty days painting two blue stripes on every tree they wanted cut—one at about chest height and a second at the base of the trunk. Evans hired Jacques to cut the wood and haul it to the mills, where he had already negotiated purchase contracts. Now that the cutting is underway, Evans checks in at least once a week. Jacques's men work all year, except when Evans shuts them down because the ground is too muddy or because they ve cut all the wood that's been marked.

Evans will sell about 8,500 cords of wood from the Grant this year, roughly a thousand truckloads. With four or five trucks rolling through the gate most days, some alumni have complained about what they see as more "intensive" management. Evans invites every critic for a tour; none has ever accepted. "That," he says, "is kind of disappointing."

So he writes long letters to explain why logging seems to be picking up. First, he explains, forestry operations have moved from the more remote west side of the property to the east, where most of the cabins and trails are. The subtler and far more important reason, however, is a fundamental change in management philosophy. Rather than the past practice of periodically cutting large quantities of the most valuable trees, the new forestry is designed to improve the quality of the forest over time. That rails for constant activity: more frequent and much lighter thinnings in more stands. Thus, a visitor is more likely to see logging trucks and active landings. They are also more likely to run into Evans, who is in the woods four days a week.

"There's not a tree cut on the Grant that a forester hasn't looked at and marked," Evans says. "My work has nothing to do with the short-term value of the wood. I don't walk up to a tree and say, 'That's worth a thousand dollars—cut it. That one's worth fifty cents—leave it. All of our forestry decisions are based on silviculture."

In public, most timber company foresters say the same thing; in private, they gripe about the constant pressure to produce cash. But Evans doesn't face those pressures, and the quality of the forestry shows. "The College is practicing exemplary forestry right now," says Staats, who sees more logging jobs in New Hampshire's North Country than anyone. "There is a real concern for the future of the forest and tremendous attention to the best silviculture."

This has not always been the case. It's safe to say that silviculture, the science of caring for a forest, was not the New Hampshire legislature's concern when it granted the land to Dartmouth College in 1807. Lawmakers were making good on an earlier land grant that had failed to earn the College any money.

When this Second College Grant attracted no more paying tenants than the First Grant had, the Trustees turned their attention to the land's only liquid asset—the trees. For a hundred years beginning in the 1850s, the Grant was periodically stripped of the most valuable wood and then left alone for a while to "recover." The same fate befell virtually every other large piece of timberland in the Northern Forest, especially those with absentee landowners like the College. First went the virgin spruce and pine trees in a lucrative but disastrous contract with timber baron George Van Dyke in the late nineteenth century. Next to go were 200,000 cords of second-growth softwoods that helped feed the Brown Company's paper mill in Berlin in the 1920s.

By the time the College hired Bob Monahan '29 as its first full time forester in 1947, the heavy timber cuts had raised more than a million dollars for scholarships and general expenses. Not surprisingly, Monahan's initial timber cruise found the land "studded with stumps." Softwood sawlog trees were virtually gone and even pulpwood was relatively scarce. Still standing, however, were some 71 million board feet of good hardwood. For the next 20 years, Monahan managed the Grant along the forestry lines of that era. He "high graded" the best yellow birch and hard maple trees, mostly for the Ethan Allan furniture factory in Vermont. He cleared out the remaining big softwood trees and all but three million board feet of hardwood sawlogs. With virtually nothing of value left, the Trustees suspended logging operations in 1967.

In 1970 the College hired two Maine companies to write and oversee a "sustained yield multiple-use" forestry plan. This first tentative turn toward a more long-term approach was stymied because there was so little decent wood left and because there was not a College forester monitoring the jobs. The contracts were terminated in 1984. The current management plan was developed by Ed Witt, who was College forester from 1986 to 1993. Evans is in his sixth year.

"Sometimes I wish Bob and the others would have left me just one nice stand of 20-inch yellow birch," Evans says, "but they didn't. For a hundred years they took the best and left the rest, and now this what we have to work with. Jungles of evenaged, pole-sized trees that need to be thinned out."

WE'VE LEFT THE ROAR of Dennis Bovin's slasher behind and are walking through the woods along the Stoddard Cabin Road. Sunlight filters down through the thin crowns of maple and birch trees, most about the diameter of a coffee can. Manhole-sized old stumps, green and spongy with moss, sprout ferns and mushrooms.

Evans has marked about half the trees to be cut in this stand, sparing the best stems in a mix of species and sizes to re-introduce age diversity. A few years after a thinning, the stand will take on a park-like look with space to walk between the trees. He points up the slope. "When you look up through there, we want you to see every diameter class represented. In 20 years we'll come back and do the same thing. We'll cut the same volume that we plan to cut this time, but there will be more wood because the trees will be a lot bigger. We'll thin right through the diameters again. Then we'll be right where we want to be."

Have no doubt that Evans knows where that is. His work is guided by a comprehensive vision statement and a management team of six people, including College lawyer Sean Gorman '76; director of outdoor programs Earl Jette; acting vice president and treasurer Win Johnson '67; acting dean of the College Dan Nelson '75; and director of Dartmouth's real estate Paul Olsen. Evans is in the eleventh year of the 20-year plan that Witt started in 1985. In the twentieth year he will begin to re-enter stands that were thinned in the mid-1980s. He will continue to initiate research projects so he can track what'g happening to the Grant's ecosystem and incorporate scientific data into his forestry plans. He will stay well within the "allowable cut"—that is, he will never cut more wood than is growing.

Evans has a head for numbers. Once a week in Dartmouth Woodlands' storefront office in Berlin (an office which will soon move north to the little town of Milan), he crunches data on timber volumes, stumpage, income, and species breakdown. He cal culates that, overall, the forest on the Grant grows at one-half cord of wood per acre per year. (This is on the high end for northern New England growth rates. Wiles and Lanier's permanent plots will provide more precise figures starting next year.) With 27,000 acres, that means the forest is growing between 12,000 and 13,000 cords a year. Anything below that figure is within what foresters call the "allowable cut." Currently the College is harvesting between 8,000 and 9,000 cords ayear, two-thirds of which is pulp. So the net growth is around 3,000 cords, and it's in the better categories.

Timber income from the Grant and from several thousand acres of College land in the Upper Valley more than pays the cost of caring for the forest. This year timber sales will cover salaries for Kevin Evans, a secretary, and Grant caretaker Lorraiue Turner; the direct costs of running the woodlands office; the building and maintaining of roads; maps and aerial photographs; and the construction of new cabins with the Outdoor Programs office. After all these expenses are covered, the College will net roughly $80,000. The College could make even more money by cutting higher-quality wood, but experience has shown that such a shortterm strategy inevitably crashes.

The simple fact is, growing and harvesting trees responsibly is a low-margin, long-term business that doesn't fit easily into a high-expectation, short term economy. Complicating this fundamental problem are the vagaries of weather, pests, equipment failure, and markets. Expenses rise steadily, while income from wood sales is notoriously volatile. Pulp and sawlog prices are linked to weather, housing starts, and other uncontrollable factors.

The way to make money without stripping the land, the College has learned, is through patience, detailed on-the-ground control, and aggressive marketing. Such careful oversight is relatively new for Dartmouth and something of an anomaly in the Northern Forest. Most large timber companies do not pay their foresters to mark each tree they want cut, for example. They give the loggers general guidelines for the size and species and leave decisions to the cutters. They save a few thousand dollars in forester pay and make a little more money for each load of wood. Shareholders are happy with high dividends, and don't question whether the company's lands are becoming more or less valuable.

Dartmouth, Evans notes, has the flexibility to do better. Cutting much less wood than is growing, and taking mostly the lower-grade trees, is akin to living off just a portion of the income from an investment. By accepting this solid but modest return in the short term, the College is building equity in the long-term viability of the Grant. And the true benefit will accrue as the forest matures.

As the quality of the trees increase over time, Evans plans to reduce the cut and increase the revenue. He has some confidence he'll be around to see that happen a faith enjoyed by too few foresters in this age of ownership changes and land sales.

"What I like about working here is I can see the results of my work. Dartmouth has owned this land for almost 200 years now, and I don't think that's going to change."

KEVIN EVANS GREW UP in Kingston, New Hampshire. He earned his forestry degree from the University of New Hampshire in 1986 and got a job with Diamond International, the old match company. He moved to northern New Hampshire and settled in. But it wasn't to last.

In 1988 Diamond sold nearly a million acres of timberland in the Northeast, much of it to developers. The sale touched off a ferocious debate over the future of the "Northern Forest" of New York and New England. "I got discouraged after Diamond sold out from under me," Evans says. "It was hard watching the land getting chunked up and cut over."

The specter of land "getting chunked up" sums up the concern over the Northern Forest, a 400-mile-long, 26-million-acre swath of woodlands that runs from Down East Maine to the Adirondacks of New York. The region contains the largest unbroken stretches of woodland in the eastern United States. Smack in the middle lies the Second College Grant.

Eighty-five percent of the Northern Forest is privately owned, much of it in huge pieces by a handful of timber corporations and investment groups from outside New England and even overseas. These lands have fed mills and provided recreation since the mid-nineteenth century. Large tracts of land changed hands frequently among the companies, but they generally remained part of the "working forest." Periods of heavy cutting in the late 1800s, 1920s, 1960s, and 1980s reflected economic and/or ecological cycles.

Diamond's land sale shook up the region because of its sheer size and the timing: At the height of the 1980s real estate boom, huge absentee landowners were selling 40-acre northern wilderness getaways and the lots were going fast. Environmentalists and North Country residents had visions of condos sprouting up around the pristine lakes and deep woods. Logging was also accelerating, and aerial views of clearcuts in regional magazines fueled the debate. National environmental groups started comparing the fight over the Northern Forest to the battles in the Pacific Northwest.

Serious differences define the two debates, however. Chief among these is the forest itself. Woodlands in the Northern Forest are not virgin old-growth; they have been cut repeatedly since before the Civil War. In the western forest conflicts, most of the land is federally owned; here it is mostly private. After a decade of studies and commissions and recommendations, including the Northern Forest Lands Council's 37 -point conservation plan of 1994, the struggle has been clearly defined as sustaining a balance between healthy forests, viable local economies, and protection of unique natural areas. In short, the question is this: Is it possible to protect a great forest without destroying the best parts of the resource-based economy that both arise from and contribute to the land?

Most would answer "yes"—possible, but not easy. Margins are slim in the wood-growing business, and the multinational companies that own much of the land are beholden to stockholders, not local residents. There's too little money for scientific research and even less for public acquisition of significant natural areas. Models of sustainable land management are rare.

Stephen D. Blackmer '79 has been at the epicenter of this debate for a decade. As past-director of conservation programs for the Appalachian Mountain Club and founding chairman of the powerful green coalition Northern Forest Alliance from 1990 to 1995, he understands the issues as well as anyone. Blackmer also knows the Grant. He took "innumerable" Outing Club trips and worked two summers there splitting wood and repairing cabins. "The College has a responsibility to manage the Grant as a model," Blackmer says. "Clearly it has the financial capacity to do it, and as an educational institution it has an ethical responsibility."

Some might argue that the College's "ethical responsibility" is to set aside the Grant as a huge ecological reserve. That view discounts the fact that the Northeastern timberlands are among the most resilient and productive in the world. With wood being one of the earth's cleanest and most renewable raw resources, others contend, keeping places like the Grant in production helps relieve the pres sure on forests in the tropics and elsewhere where logging is unsustainable. Turning the Grant into a private park, just because Dartmouth has the means to do that, is arguably less ethical than continuing sustainable forestry.

Although he has not been on the Grant for a few years, Blackmer endorses the current management vision as an example of enlightened "new forestry." He would like to see the College take several more steps: legally protecting the land with a conservation easement that would permanently prohibit intensive development; applying for third-party "green certification" of wood products from the Grant (something that is prohibitively expensive right now for the Grant's relatively small volume of sawlogs, says Win Johnson); and permanently setting aside some no-cut zones for ecological research.

"just think what a landowner like Dartmouth could show about how to blend ecological principles with quality timber production. That's what the future of the Northern Forest is all about."

Kevin Evans agrees. He'd like to see all activities increased on the Grant—good forestry, scientific research, and interpretation. He has hosted freshman orientation trips for three years running and is trying to get more Dartmouth faculty members to use the land for research such as the woodcock studies.

"I tell them, if you find something, let me know. I'll draw a circle around it and we'll leave that area alone. It's exciting to think ahead. If we're around long enough, we'll be able to come back and see if what we had anticipated was going to happen did happen."

THE WOODCOCK NEVER did fall for the flashlight-and-net technique. In September, however, the first of several birds fluttered into a stationary net and was radio-collared. Every day for the next month the bird led the biologists on his daily flights. Each night he returned to roost in the same grassy strip along the Swift Diamond River.

In October he headed south. Somewhere over Pennsylvania the radio's batteries went dead. Several hundred miles further, after he had slimmed down from the long flight,

the collar slipped away and fell into a field in Louisiana. That's fine. He left an important bit of data behind in a computer in Berlin, New Hampshire. Chances are better than average he'll return next spring to the safe roosting area in the Second College Grant. Chances are excellent that his progeny will follow the same route for generations to come, and find the Grant's well-tended woods waiting.

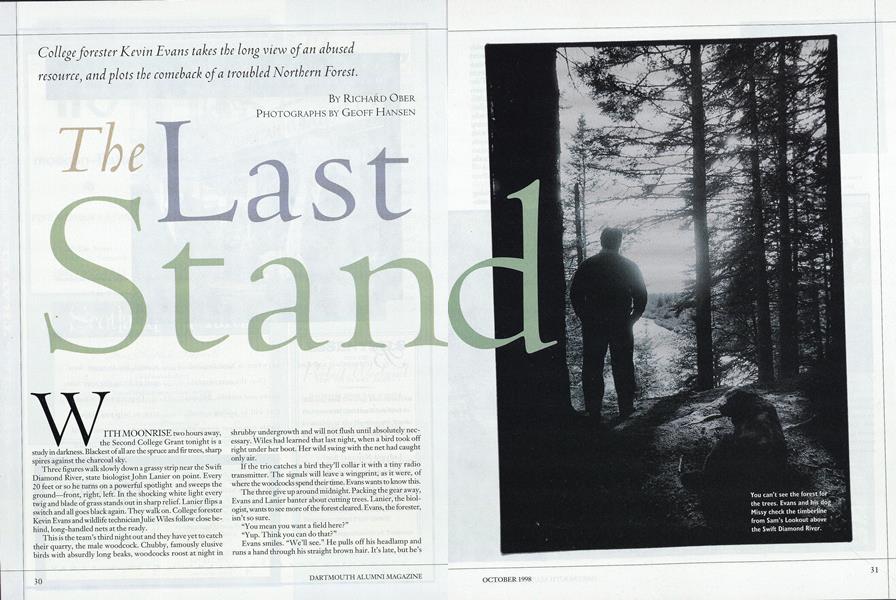

You can't see the forest for the trees.Evans and his dog Missy check the timberline from Sam's Lookout above the Swift Diamond River.

A mechanical Paul Bunyan, feller bunchers run by loggers like Luc Lapierre sent the blue ox Babe out to pasture. The machine, which cuts and lays down trees, has cut down logger injuries...

...but chainsaw work remains dirty and dangerous.

Quebec-based logger Marcel Larochelle (left) and Grant forester Kevin Evans talk business—in this case minimizing the damage done by the skidders. There's not a tree cut on the Grant that a forester hasn't first looked at and marked.

The Grant is a 27,000- acre lab for wildlife managers. Julie Wiles, a biologist with the state, pinpoints crucial animal habitats with a satellite mapping computer.

A timber pile offers a perch for Wiles, who scans for a songbird she's identified near a logging yard in Loomis Valley.

RICHARD OBER, co-author of The Northern Forest, is the senior director for outreach programs for the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests.

It's safe to say that silviculture,the science of caring for aforest, was not the legislature'sconcern when it granted the landto Dartmouth in 1807.

"Sometimes I wishBob Monahan and the otherswould have left me just onenice stand of 20-inch yellowbirch,"Evans says.Evans invites every criticfor a tour; none has everaccepted. "That," he says,"is kind of disappointing

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLOST IN THE TREASURE ROOM

October 1998 By Brock Brower '53 -

Feature

FeatureNomss de Blitz

October 1998 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

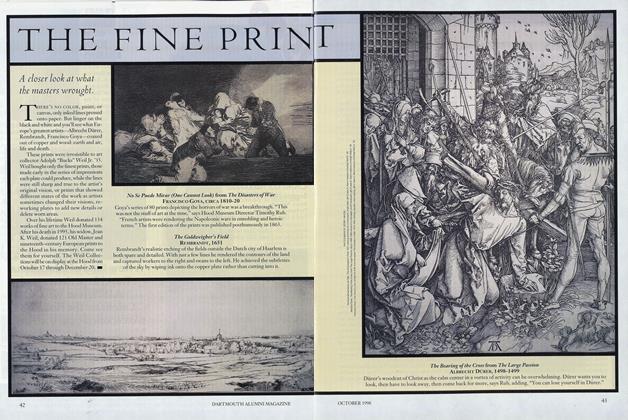

FeatureTHE FINE PRINT

October 1998 -

Article

ArticleA Thankless Job (Because You Didn't Know Who to Thank)

October 1998 -

Article

ArticleWhen a Kid Goes Green, Getting In Is Only the Beginning

October 1998 By Mom -

Class Notes

Class Notes1986

October 1998 By Davida (Sherman)