The year Dartmouth took the nation and changed a sport forever.

The fall of 1925 was a season of glory. Calvin Coolidge was in the White House; Jimmy Walker won the New York mayoralty; Walter Johnson pitched the Washington Senators to a World Series triumph; and in Europe a historic security conference was just getting underway.

In Hanover, a new curriculum permitted greater scholastic freedom; mandatory daily chapel service was abolished; rushing of freshmen by fraternities was banned; the Trustees voted to build Baker Library and a new field house; a student referendum supported a World Court; and President Ernest Martin Hopkins urged every student to have the "stamina and courage" to attain his own maximum ability.

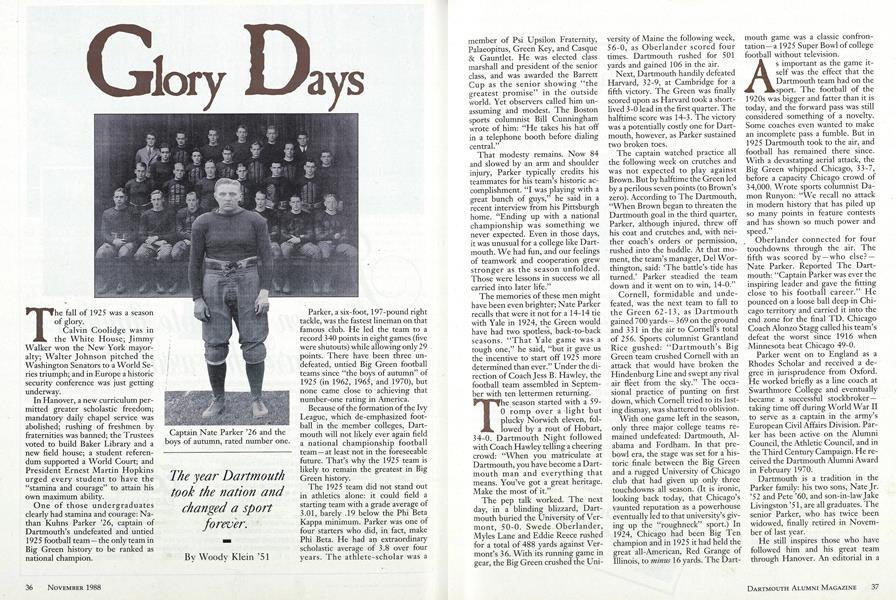

One of those undergraduates clearly had stamina and courage: Nathan Kuhns Parker '26, captain of Dartmouth's undefeated and untied 1925 football team-the only team in Big Green history to be ranked as national champion.

Parker, a six-foot, 197-pound right tackle, was the fastest lineman on that famous club. He led the team to a record 340 points in eight games (five were shutouts) while allowing only 29 points. There have been three unefeated, untied Big Green football teams since "the boys of autumn" of 1925 (in 1962, 1965, and 1970), but none came close to achieving that number-one rating in America.

Because of the formation of the Ivy League, which de-emphasized football in the member colleges, Dartmouth will not likely ever again field a national championship football team—at least not in the foreseeable future. That's why the 1925 team is likely to remain the greatest in Big Green history.

The 1925 team did not stand out in athletics alone: it could field a starting team with a grade average of 3.01, barely .19 below the Phi Beta Kappa minimum. Parker was one of four starters who did, in. fact, make Phi Beta. He had an extraordinary scholastic average of 3.8 over four years. The athlete-scholar was a member of Psi Upsilon Fraternity, Palaeopitus, Green Key, and Casque & Gauntlet. He was elected class marshall and president of the senior class, and was awarded the Barrett Cup as the senior showing "the greatest promise" in the outside world. Yet observers called him unassuming and modest. The Boston sports columnist Bill Cunningham wrote of him: "He takes his hat off in a telephone booth before dialing central."

That modesty remains. Now 84 and slowed by an arm and shoulder injury, Parker typically credits his teammates for his team's historic accomplishment. "I was playing with a great bunch of guys," he said in a recent interview from his Pittsburgh home. "Ending up with a national championship was something we never expected. Even in those days, it was unusual for a college like Dartmouth. We had fun, and our feelings of teamwork and cooperation grew stronger as the season unfolded. Those were lessons in success we all carried into later life."

The memories of these men might have been even brighter; Nate Parker recalls that were it not for a 14-14 tie with Yale in 1924, the Green would have had two spotless, back-to-back seasons. "That Yale game was a tough one," he said, "but it gave us the incentive to start off 1925 more determined than ever." Under the direction of Coach Jess B.Hawley, the football team assembled in September with ten lettermen returning.

The season started with a 590 romp over a light but plucky Norwich eleven, followed by a rout of Hobart, 34-0. Dartmouth Night followed with Coach Hawley telling a cheering crowd: "When you matriculate at Dartmouth, you have become a Dartmouth man and everything that means. You've got a great heritage. Make the most of it."

The pep talk worked. The next day, in a blinding blizzard, Dartmouth buried the University of Vermont, 50-0. Swede Oberlander, Myles Lane and Eddie Reece rushed for a total of 488 yards against Vermont's 36. With its running game in gear, the Big Green crushed the versity of Maine the following week, 56-0, as Oberlander scored four times. Dartmouth rushed for 501 yards and gained 106 in the air.

Next, Dartmouth handily defeated Harvard, 32-9, at Cambridge for a fifth victory. The Green was finally scored upon as Harvard took a short lived 3-0 lead in the first quarter. The halftime score was 14-3. The victory was a potentially costly one for Dartmouth, however, as Parker sustained two broken toes.

The captain watched practice all the following week on crutches and was not expected to play against Brown. But by halftime the Green led by a perilous seven points (to Brown's zero). According to The Dartmouth, "When Brown began to threaten the Dartmouth goal in the third quarter, Parker, although injured, threw off his coat and crutches and, with neither coach's orders or permission, rushed into the huddle. At that moment, the team's manager, Del Worthington, said: 'The battle's tide has turned.' Parker steadied the team down and it went on to win, 14-0."

Cornell, formidable and undefeated, was the next team to fall to the Green 62-13, as Dartmouth gained 700 yards-369 on the ground and 331 in the air to Cornell's total of 256. Sports columnist Grantland Rice gushed: "Dartmouth's Big Green team crushed Cornell with an attack that would have broken the Hindenburg Line and swept any rival air fleet from the sky." The occasional practice of punting on first down, which Cornell tried to its lasting dismay, was shattered to oblivion.

With one game left in the season, only three major college teams remained undefeated: Dartmouth, Alabama and Fordham. In that prebowl era, the stage was set for a historic finale between the Big Green and a rugged University of Chicago club that had given up only three touchdowns all season. (It is ironic, looking back today, that Chicago's vaunted reputation as a powerhouse eventually led to that university's giving up the "roughneck" sport.) In 1924, Chicago had been Big Ten champion and in 1925 it had held the great ail-American, Red Grange of Illinois, to minus 16 yards. The Dartmouth game was a classic confrontation—a 1925 Super Bowl of college football without television.

As important as the game itself was the effect that the Dartmouth team had on the sport. The football of the 1920s was bigger and fatter than it is today, and the forward pass was still considered something of a novelty. Some coaches even wanted to make an incomplete pass a fumble. But in 1925 Dartmouth took to the air, and football has remained there since. With a devastating aerial attack, the Big Green whipped Chicago, 33-7, before a capacity Chicago crowd of 34,000. Wrote sports columnist Damon Runyon: "We recall no attack in modern history that has piled up so many points in feature contests and has shown so much power and speed."

Oberlander connected for four touchdowns through the air. The fifth was scored by-who else?- Nate Parker. Reported The Dartmouth: "Captain Parker was ever the inspiring leader and gave the fitting close to his football career." He pounced on a loose ball deep in Chicago territory and carried it into the end zone for the final TD. Chicago Coach Alonzo Stagg called his team's defeat the worst since 1916 when Minnesota beat Chicago 49-0.

Parker went on to England as a Rhodes Scholar and received a degree in jurisprudence from Oxford. He worked briefly as a line coach at Swarthmore College and eventually became a successful stockbrokertaking time off during World War II to serve as a captain in the army's European Civil Affairs Division. Parker has been active on the Alumni Council, the Athletic Council, and in the Third Century Campaign. He received the Dartmouth Alumni Award in February 1970.

Dartmouth is a tradition in the Parker family: his two sons, Nate Jr. '52 and Pete '60, and son-in-law Jake Livingston '51, are all graduates. The senior Parker, who has twice been widowed, finally retired in November of last year.

He still inspires those who have followed him and his great team through Hanover. An editorial in a November 1925 issue of The Dartmouth called that team "the greatest that has ever graced the gridiron," and said it had "elevated itself to a niche in the Hall of Fame."

Since then, Dartmouth's football fortunes have risen and fallen. Fans particularly lament last year's showing when the team gave up 302 points, a new school record; scored only 110 points, the fewest since 1974; and had the worst record (2-80) since Coach Tuss McLaughry's war-riddled 1945 squad went 1-6-1. Even worse, Dartmouth was rated by USA Today one hundred eightyeighth among some 191 Division 1A and 1-AA college football teams. Only Columbia (0-10-0), Morgan State and Davidson (1-10-0) were rated lower.

Dartmouth excels in other ways, of course, and sacrifices must be made to that excellence. The College was rated sixth among elite schools in a recent poll of university presidents. An astonishing mix of skills and cultural backgrounds compose the student body. As the numbers of applicants soar, the school can afford to be more selective than ever. And President James O. Freedman promises to take Dartmouth onto an even higher intellectual plane.

Dartmouth may be an elite school in America today-this observer certainly believes it is-but its football team is not. It's obvious that Dartmouth football has reached a new low—and that is causing concern in alumni circles. Many of us do not want to lose a generations-old tradition of fielding winning football teams. It's part of the Dartmouth spirit. It comes with the Hanover territory. In my day, Dartmouth was always at or near the top of the Ivy League standings. It was expected. All of us counted on it. We still do.

In future years, Dartmouth football may well come to dominate the Ivy League once more, even as it rises in the academic standings. But the College will almost certainly never reach the exquisite plateau of that 1925 team. Perhaps that is as it should be. But it still hurts to know that those days are forever gone.

A season of glory, indeed.

Captain Nate Parker '26 and the boys of autumn, rated number one

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDaughters of Dartmouth

November 1988 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureThe Helplessness of a "Bureaucrat of Legendary Proportions"

November 1988 By Jonathan Cowan '87 -

Feature

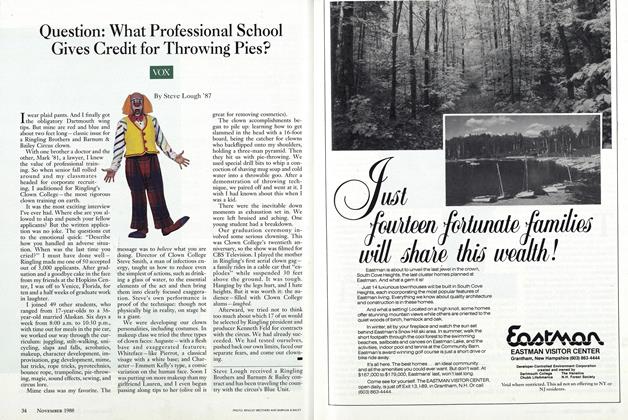

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

November 1988 By Steve Lough '87 -

Feature

FeatureGetting Gored by a Rhinoceros Was Only Half the Experience

November 1988 By Emily Hill '90 -

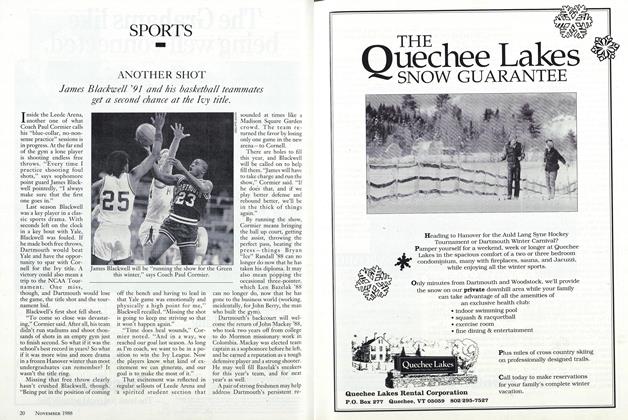

Sports

SportsANOTHER SHOT

November 1988 -

Article

ArticleSHOULD DARTMOUTH DIVEST?

November 1988

Woody Klein '51

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JANUARY 1971 -

Article

ArticleHavel Should Come to Dartmouth

April 1993 By Woody Klein '51 -

Feature

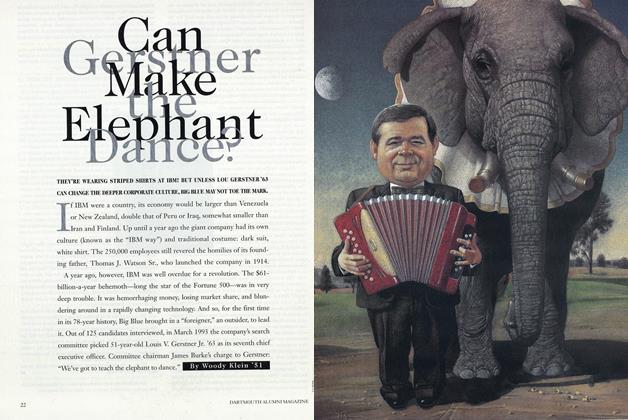

FeatureCan Gerstner Make the Elephant Dance?

MARCH 1994 By Woody Klein '51 -

Article

ArticleFull Cycle

Novembr 1995 By Woody Klein '51 -

Feature

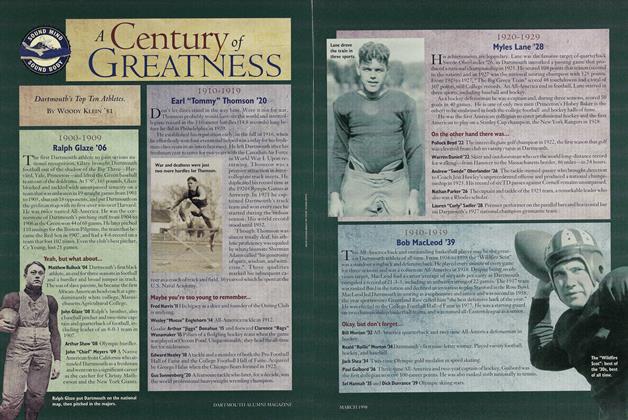

FeatureA Century of Greatness

March 1998 By Woody Klein '51

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryArms Limitations in Webster's Time

June 1989 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

MAY | JUNE -

Feature

FeaturePLATT

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BUILD YOUR OWN IGLOO

Jan/Feb 2009 By NORBERT YANKIELUN, TH'92 -

Feature

FeatureTHE CLASSICS

March 1962 By NORMAN A. DOENGES -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIntelligent Life

MARCH 1995 By Sasha Verkh '95