The Helplessness of a "Bureaucrat of Legendary Proportions"

NOVEMBER 1988 Jonathan Cowan '87FIRST PERSON

Without a watch, I had to trust my stomach, which told me that it must have been a little past noon. Since the only window was small and dirty, I couldn't see much of the sun. I ignored my stomach, then pulled the next case from the top of the stack, took four forms from four other stacks, and read the summary while filling in all of the blanks.

"Complainant: Eva Woods. Potential Defendant: Larry Woods. Married 10 years. Two Children. One Prior Complaint. In this new incident, he threatened to kill her, held a knife to her throat, she escaped with the kids. Recommendation: Police and Warning Letter."

With the forms ready, I walked down the hall into a dirty room, about the size of my bedroom, and called for Mrs. Woods.Eighty women's eyes turned my way, each hoping I had called the wrong name. A young woman stood up and nodded her head, and we moved down the hall toward the office. She was obviously familiar with the route.

"Mrs. Woods, have you had to wait long?" (I knew she had.) "Mrs. Woods, please take a seat. Though I'm not an attorney, I represent Corporation Counsel. I've looked over your case, and you have a few options." She proceeded to tell me what they were: "This is a civil case, not criminal. You can't put him in jail. I can get a police letter. You can send a warning letter to my husband telling him that you're aware of the problem and may take action. Or I can get a civil protection order, keeping him away from me for a year." Her voice was even, without a trace of anger. It was exactly what I would have told her.

I asked her if she had any bruises or injuries. None. Had she threatened her husband? Yes, she had hit him with a pot. Why? She said it was to protect herself, her children. To teach him a lesson.

"Mrs. Woods, if you leave your house..." She cut me off, explaining that she had paid all the rent. "And I'm not going to let him jew me down again," she added. (I'm Jewish; it didn't ingratiate her).

"Okay, but for your safety and the children's, if you leave, do you have anywhere else to go, any family or friends?" She had no family and only one friend, an old woman in a seniors home. They could stay three, maybe four days in the home. A court appearance would take at least three weeks.

"What about a shelter?" I asked. She looked at me with disgust and started to cry. We both knew that only an abusive, indifferent mother would take her children to the filthy shelters.

I stood up from behind the desk' and turned to look out, or at, the small window in the corner. I knew she'd have to go prose, to represent herself; we couldn't take her. The charges were shaky, she had no scars, she had attacked him, we had too many cases.

I felt like a bureaucrat of legendary proportions. I had thought of myself as a good listener and a good salesman; every case I heard I tried carefully to differentiate from all the others, to give constructive, pragmatic advice. I tried to discuss what I saw as the biggest difficulties, find out what she perceived as her real needs, and persuasively suggest what I saw as a workable solution. Each time I felt slightly embarrassed at entering into people's lives so quickly. But now, where could I tell her to stay?

I thought about how much easier it was for me to create marketing campaigns, write public-relations "pitch" letters, or research a thesisa-ll of which I had done before graduating from Dartmouth. Checking off the right boxes on my forms certainly wouldn't produce adequate temporary shelter or a good solution. She could leave the kids with her husband until court. Sure: "Mrs. Woods, leave the children with your knife-wielding, unemployed husband."

I turned toward her and leaned across the desk. I thought I'd tell her the worst part first. "Mrs. Woods, we can't represent you. Although I'd like to...She cut me off. "I know. No scars, I attacked him." I looked at her expecting to see intense anger. The tears had stopped. Instead she smiled at me. "Well, what can you do? Where can I stay?"

It scared me; with that smile, she must have known how uncomfortable I felt with my hands tied behind my back. "Mrs. Woods, I don't know where you should go. I can only give you the pro se papers."

She clutched the papers, smiled again and told me that it was okay. She said she was glad she didn't have my job, where she'd have to see people's problems and not be able to help them. Then she got up and left, in Washington, D.C. Child-abuse cases were his purview; as part of his work he counseled victims at the Battered Women's Shelter, a center for women seeking legal (and often personal) advice about divorce, civil protection or child custody. This essay tells of one such encounter. Cowan now works for the Washington-based group Rebuild America, a bipartisan national coalition that is devising an "investment economics" to replace supply-side doctrine.

"Eighty women'seyes turned my way,each hoping Ihad called thewrong name."

Shortly after graduating from Dartmouth last year,Jonathan Cowan '87 went to work for a public prosecutor

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

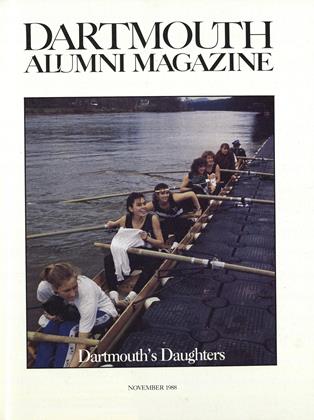

Cover StoryDaughters of Dartmouth

November 1988 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureGlory Days

November 1988 By Woody Klein '51 -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

November 1988 By Steve Lough '87 -

Feature

FeatureGetting Gored by a Rhinoceros Was Only Half the Experience

November 1988 By Emily Hill '90 -

Sports

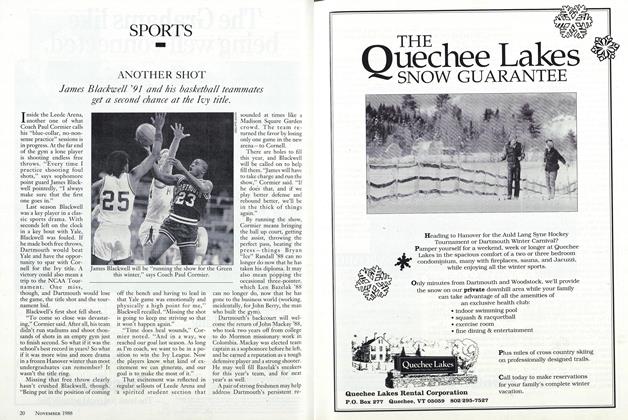

SportsANOTHER SHOT

November 1988 -

Article

ArticleSHOULD DARTMOUTH DIVEST?

November 1988

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE THEME IS CHANGE

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureVANISHING ABSOLUTES

DECEMBER 1964 -

Feature

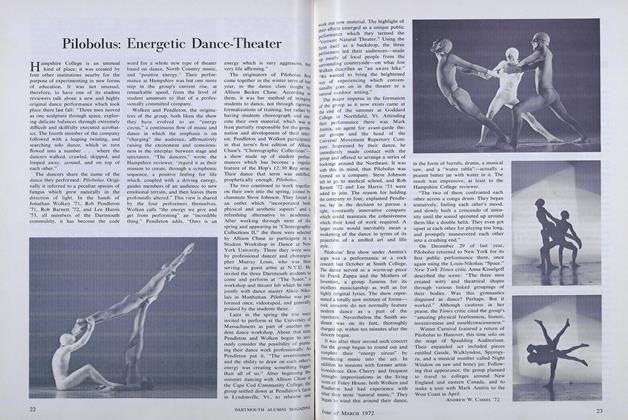

FeaturePilobolus: Energetic Dance-Theater

MARCH 1972 By ANDREW W. CASSEL '72 -

Feature

FeatureChallenge

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Colleen Sullivan Bartlett '79 -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

MARCH 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Feature

FeatureThe Teacher of Social Science and the World Crisis

February 1954 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS