Can Dartmouth attract President Freedman's"daring dreamers"? We think it already has.

SURELY YOU have read by now the famous phrases from the president's inaugural address, in which he called for making Dartmouth more attractive to "creative loners and daring dreamers" who "march to a different drummer."

Naturally, President Freedman does not envision an entire campus filled with lonely dreamers. He acknowledges a place for the well-rounded student of Dartmouth tradition. Nonetheless, some critics (and a number of admirers) responded to Freedman's words as if they were revolutionary as if he were introducing a strange new element to the College.

We asked Photo Editor Nancy Wasserman to test our hypothesis that some of these coveted "different drummers" already exist at Dartmouth. Could she find a dozen highly focused students who had accomplished something impressive? Two weeks after we asked, she came up with more than 40. We whittled the list down to seven and asked Charlie Wheelan '88, author of the March cover story on student entrepreneurs, to write short biographies.

Each of these students has devoted more time to a particular skill or goal than to the Dartmouth social scene. And yet, none is exactly misanthropic, or even what their peers would call "geeky." For that matter, just about all of them could be called well-rounded. Maybe Dartmouth some how diversifies the individual. Or maybe the true monomaniac is rare on any campus.

In any case, the students here are among the best at what they do, and that is a Dartmouth tradition that goes way back. Ed.

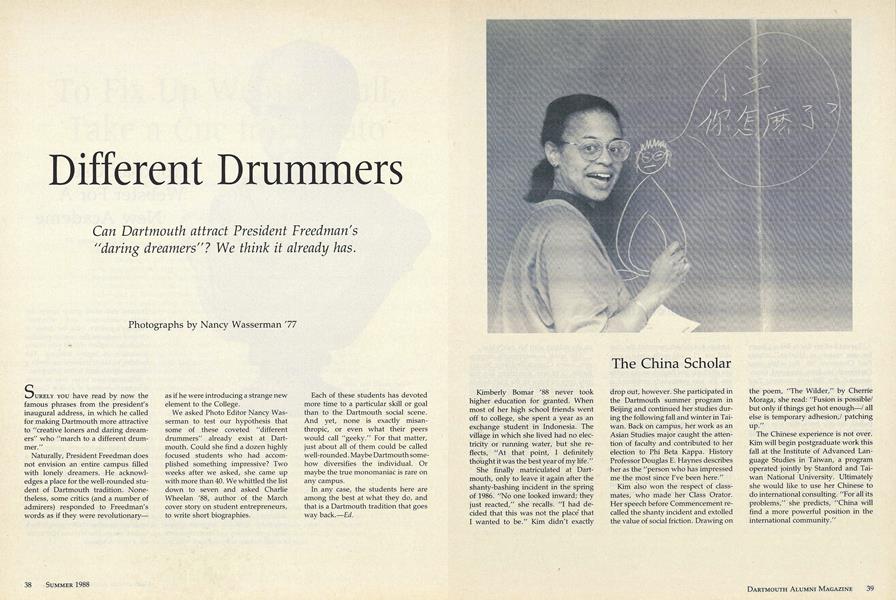

Kimberly Bomar '88 never took higher education for granted. When most of her high school friends went off to college, she spent a year as an exchange student in Indonesia. The village in which she lived had no electricity or running water, but she reflects, "At that point, I definitely thought it was the best year of my life."

She finally matriculated at Dartmouth, only to leave it again after the shanty-bashing incident in the spring of 1986. "No one looked inward; they just reacted,' she recalls. "I had decided that this was not the place' that I wanted to be." Kim didn't exactly drop out, however. She participated in the Dartmouth summer program in Beijing and continued her studies during the following fall and winter in Taiwan. Back on campus, her work as an Asian Studies major caught the attention of faculty and contributed to her election to Phi Beta Kappa. History Professor Douglas E. Haynes describes her as the "person who has impressed me the most since I've been here."

Kim also won the respect of classmates, who made her Class Orator. Her speech before Commencement recalled the shanty incident and extolled the value of social friction. Drawing on the poem, "The Wilder," by Cherrie Moraga, she read: "Fusion is possible/ but only if things get hot enough /all else is temporary adhesion,/ patching up."

The Chinese experience is not over. Kim will begin postgraduate work this fall at the Institute of Advanced Language Studies in Taiwan, a program operated jointly by Stanford and Taiwan National University. Ultimately she would like to use her Chinese to do international consulting. "For all its problems," she predicts, "China will find a more powerful position in the international community."

"I spent half my life in Baker Library for one reason or another," admits Paul Christesen '88. But while most Dartmouth students struggled to understand the library's system, Paul helped reorganize it. As a student member of the Library Council, he noticed that some rare and valuable books were allowed to circulate."I pulled out one book that was worth $5,000," he says. The library soon acted to ensure that valuable manuscripts would not end up wedged between pizza boxes in the dorm rooms of unknowing undergraduates; the books have been added to Special Collections.

But Paul's most serious work in Baker was his research on the Greek Archaic Era, which preceded the classical era."I could really make a contribution," he says, noting that there are relatively few English works on the era. He was particularly interested in Greek athletics, since they were such an integral part of the culture.

Paul went on a Dartmouth foreignstudy program to Greece where he began to research the gymnasium, the Greek forerunner to the modern gym. After the year 600 B.C., the daily ritual for Greek men was to exercise and compete in track and field events. "The best way to think of the gymnasium is as the ancient equivalent of the country club," Paul explains. His interest evolved into a senior honors thesis in which he synthesized French literature on the subject with his own ideas.

"His work is enormously impressive," says Classics Professor Jeremy Rutter. "I've seen something like this only once or twice in the past decade at Dartmouth." If Paul can whittle his thesis from 75 to 20 pages, he will try to have it published.

He hopes eventually to enter academia as a professor of ancient history. In the meantime, he is taking a year off to work in a bicycle shop in New York City. "Fixing bikes cleanses the mind," Paul contends. His other chief interest is squash, a "thinking man's game." Mind and body clearly go well together for him. He says, smiling, "Athletics in the archaic era is the new wave in ancient history."

A clause recurs whenever Elizabeth Sawin '88 speaks: "If we can understand how this happens..."The attitude is appropriate for someone who threw herself into cancer research as an undergraduate.

In Beth' s senior fellowship, titled "An Approach for the Study of the Differentiation of Murine Erythroleukemia Cells," she explored the process in which chemically treated leukemia cells in mice acquire the characteristics of red blood cells. This reverses the transformation that blood cells undergo in leukemia victims.

To understand how this happens, Beth logged marathon lab sessions of up to 24 hours, performing "at the level of an advanced graduate student," according to Biology Professor Robert H. Gross. Seven or eight academic citations in four years (she has won too many to remember the exact count) have been one result. Beth has received a grant from the Milheim Foundation to continue her work at Dartmouth for one more year. Graduate work, teaching and research should follow.

She does have spare time which she spends on reading, canoeing, hiking, biking, and other "standard outdoor things." She is also involved in Beyond War, a national nonpartisan group that tries to change the way people view armed conflict in the age of nuclear weapons. Beth admits, "You need some kind of balance between your work and everything else in your life." Devon Petty '88 is not particularly philosophical when he discusses his decision to come to Dartmouth from his home in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. "I just looked in a catalogue and there it was," he says. As a budding computer jockey, he did know that Hanover was where the BASIC computer language had been developed. As a jazz musician, he was not sure how his talents would contribute to the campus.

Devon first won fame among fellow '88s during freshman year, when he wrote a program similar to the popular video game "Breakout" and made it available to friends in the dorm. "Nobody got any work done," recalls classmate Stephen Moran.

But Devon didn't stop with video games. As an undergraduate he created a program for the Apple Macintosh that modifies sound waves and synthesizes new sounds. At the suggestion of Music Professor Jon Appleton, Devon went to work parttime for the Vermont-based company New England Digital. There he created the Pericom Graphics Terminal Emulator, a program that links the Macintosh to more sophisticated music machines. The software package previewed at the National Association of Broadcasters Convention and is now being distributed commercially.

Back at Dartmouth, one of his computer programs won second prize in the Kemeny Computer Competition, and he was twice awarded the Distinguished Service and Academic Achievement Award by the Afro-American Society.

Devon nonetheless contends that he did not spend much time in the computer science department. The competing interest is jazz music. He played bass guitar for the Barbary Coast, although the instrument he first learned in the Virgin Islands was the trumpet. He also performed with the Polyrhythms, a jazz group that recently won the New Hampshire Battle of the Bands.

Next year Devon will return to the Virgin Islands to consult, teach, and program computers. The computer work and music are intimately related. At Dartmouth, he studied under Professor Appleton, chairman of the music department and a pioneer in electronic music. Since then, most of Devon's computer work has focused on bringing music and sound to the Apple Macintosh. He contends that the combination has the artistry of music and the tangible finished product of a computer program. "After you've completed something, you can say, 'This is what I've done.' "

Brendan MacLean '89 dabbled in photography, acting, kayaking, and a myriad of other typical Dartmouth activities when he arrived in Hanover for his freshman year. Something wasn't right, however. "I felt like I was spreading myself too thin," he recalls. "I wanted to be really good at something." Kayaking was the activity that pleased him most, so in the fall of 1985 he committed himself to the Connecticut River.

As a Hanover native, Brendan had logged a fair number of hours at the Ledyard Canoe Club while still in high school. During his senior year at Hanover High, he worked out with Dana Chladek '85, a member of the U.S. Women's Kayaking Team. She convinced him to enter the U.S. Junior Nationals, where he finished second to last—saved from total defeat only by his best friend, who had also agreed to compete.

Then, after some freshman year drifting at Dartmouth, Brendan got really serious. He sought out good Whitewater practice areas. When the rivers were impassable, he lifted weights. In the spring, he tried the Junior Nationals again and came in second. He is now ranked fifteenth in the United States, based on his best races, and he currently paddles the third boat on the New England kayaking team.

His training has taken him from Seattle to Costa Rica, often on a shoestring budget. After freshman spring, Brendan sold his textbooks back to the Dartmouth Bookstore to pay for a training camp. He borrowed food money and slept on a friend's floor to avoid paying rent. When the textbook money was exhausted, he went to work at the McDonald's near the training site, to support his kayaking habit.

A computer science major, Brendan describes his college experience as "the year-on, year-off program." Coming to Dartmouth with six college credits, he left school after freshman year to go kayaking. He expects to take the next year off as well. When he finally does graduate, he plans to have an education certificate that would qualify him to teach.

Despite all his sacrifices, Brendan receives little recognition on campus. Such is the drawback of a low-profile sport like kayaking. When he outpaced skiers, hikers and football stars to win a triathlon at Dartmouth last summer, it was the first time that most students had seen his name in print. His sport will soon receive a boost, however. At the 1992 Summer Olympics in Spain, kayaking will be an official event for the first time in 20 years. Brendan is vague about the future, but he is certain about one short-term goal: "I'm definitely kayaking until '92."

"The more languages you know, the easier it is to learn more,' says Harmeet Dhillon '89. She presently speaks or writes French, Latin, ancient Greek, Punjabi, Urdu, Hindi and English.

Although she was just six months old when she immigrated to the United States, Harmeet has nonetheless retained her identity as a Sikh from the Punjab. Since freshman spring she has lived alone off campus so that she can pray daily in her own prayer room. This summer, Harmeet and her father, a surgeon in North Carolina, plan to write a historical and journalistic account of the conflict in the Punjab. The Dhillons have been blacklisted in India for espousing the Sikh cause.

Harmeet's political activism is not limited to east Asia. She is also a senior editor of the Dartmouth Review and a student employee of the Hopkins Institute. She denies that there is any incongruity between these critics of affirmative action and her own work for Indian minorities. "God helps those who help themselves," she says. "Sikhs do well in this country. We do not respect those who take handouts."

Harmeet devotes her spare time to painting, sewing, writing, and classical music. She chose to study the classics, a major she describes as "difficult and rare." Next year she will spend a term in Greece researching a thesis on the development of ostracism in Athens.

She has no apologies for her work on the Dartmouth Review. "I'm offended by most of the liberal publications on campus, but I don't complain about it. I have an outlet just like them."

Cuong Do '88, T'89 must be the first Phi Beta Kappa graduate in recent memory to avoid the Dartmouth Book store. "Since sophomore year I haven't bought books," he says quietly. "I have a near photographic memory. I can go to class, pick things up, and learn them that way."

A native of Vietnam, he left the country at the age of nine in 1975 when the family fled the North Vietnamese invasion, leaving all their possessions behind. The experience has given Cuong a powerful drive to succeed. He double majored in biochemistry and economics while fulfilling premed requirements. During his junior year he researched and wrote an honors thesis (a task normally undertaken only by seniors) in which he attempted to isolate the protein responsible for chemical transport in cells.

He also became the first Dartmouth student in three years to be accepted into the Amos Tuck 3-2 program. While finishing his bachelor of arts degree he worked toward an to be awarded next spring. After that he will attend Stanford Medical School, which has already accepted him. Eventually, he would like to start a free clinic.

Why go to business school if he plans a career in medicine? His answer is a standard piece of wisdom: "Doctors are usually the worst businessmen."

Cuong also contradicts the premed stereotype with a remarkable set of avocations. He participated in Dartmouth's music foreign-study program in London as well as the College's government program in Budapest. He sings, composes classical music, and is working on an opera ("a very longterm project"). He founded Vox Bacchi, a group of friends who convene once a week to taste wine.

His greatest single contribution to the College, however, has been his crusade for safer sex on campus. As president of the Nathan Smith Society, Dartmouth's premed organization, he was instrumental in distributing condoms and safer-sex kits on campus. This led to an appearance on "Phil Donahue," where he faced off against Dartmouth Review Editor Deborah Stone '87 to debate the kits' merits.

"To me it was no big deal," Cuong says of his involvement in the cause of sexual safety. "It was something I believed in. Politically I'm a very conservative person, but when it comes to life or death, conservatism has no meaning."

The China Scholar

The Scholar of Athletes

The Biologist

The Computer Musician

The Kayaker

The Linguist

The Health Provider

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSUBJECT: HALF OF HUMANITY

June 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Feature

FeatureRising Sophomore

June 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureCommencement '88

June 1988 -

Feature

FeatureTo Fix Up Webster Hall, Take a Cue from Plato

June 1988 By Brad Denny '63 -

Feature

FeatureNext Month: A (Not Altogether) New Look

June 1988 -

Feature

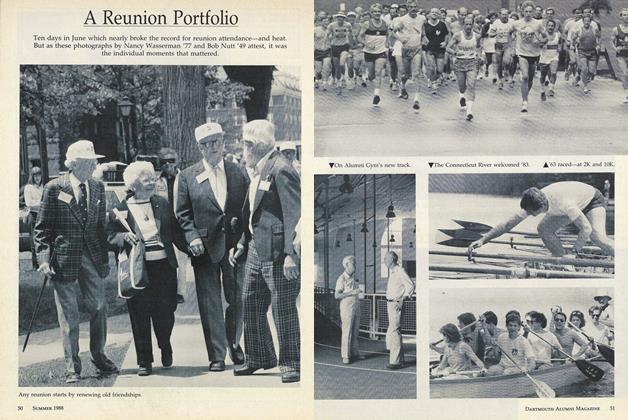

FeatureA Reunion Portfolio

June 1988

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

FeatureThe Old Guard

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Mike McGean '49 -

Feature

FeatureOff the Beaten Path

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

Feature

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

Feature"Dartmouth Visited"

October 1956 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe View from Oxford

NOVEMBER 1971 By Sanford B. Ferguson '70