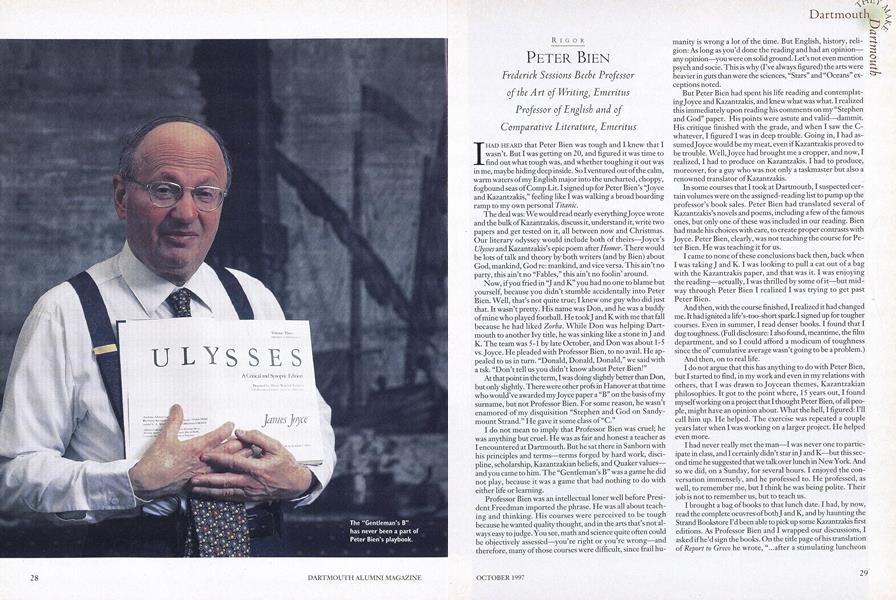

Frederick Sessions Beebe Professorof the Art of Writing, EmeritusProfessor of English and ofComparative Literature, Emeritus

I HAD HEARD that Peter Bien was tough and I knew that I wasn't. But I was getting on 20, and figured it was time to find out what tough was, and whether toughing it out was in me, maybe hiding deep inside. So I ventured out of the calm, warm waters of my English major into the uncharted, choppy, fogbound seas of Comp Lit. I signed up for Peter Bien's "Joyce and Kazan tzakis," feeling like I was walking a broad boarding ramp to my own personal Titanic.

The deal was: We would read nearly everything Joyce wrote and the bulk of Kazantzakis, discuss it, understand it, write two papers and ,get tested on it, all between now and Christmas. Our literary odyssey would include both of theirs—Joyce's Ulysses and Kazantzakis's epic poem after Homer. There would be lots of talk and theory by both writers (and by Bien) about God, mankind, God re: mankind, and vice versa. This ain't no party, this ain't no "Fables," this ain't no foolin' around.

Now, if you fried in "J and K" you had no one to blame but yourself, because you didn't stumble accidentally into Peter Bien. Well, that's not quite true; I knew one guy who did just that. It wasn't pretty. His name was Don, and he was a buddy of mine who played football. He took J and K with me that fall because he had liked Zorba. While Don was helping Dartmouth to another Ivy title, he was sinking like a stone in J and K. The team was 5-1 by late October, and Don was about 1-5 vs. Joyce. He pleaded with Professor Bien, to no avail. He appealed to us in turn. "Donald, Donald, Donald," we said with a tsk. "Don't tell us you didn't know about Peter Bien!"

At that point in the term, I was doing slightly better than Don, but only slightly. There were other profs in Hanover at that time who would've awarded my Joyce paper a "B" on the basis of my surname, but not Professor Bien. For some reason, he wasn't enamored of my disquisition "Stephen and God on Sandy-mount Strand." He gave it some class of "C."

I do not mean to imply that Professor Bien was cruel; he was anything but cruel. He was as fair and honest a teacher as I encountered at Dartmouth. But he sat there in Sanborn with his principles and terms—terms forged by hard work, discipline, scholarship, Kazantzakian beliefs, and Quaker values and you came to him. The "Gentleman's B" was a game he did not play, because it was a game that had nothing to do with either life or learning.

Professor Bien was an intellectual loner well before President Freedman imported the phrase. He was all about teaching and thinking. His courses were perceived to be tough because he wanted quality thought, and in the arts that's not always easy to judge. You see, math and science quite often could be objectively assessed—you're right or you're wrong and therefore, many of those courses were difficult, since frail humanity is wrong a lot of the time. But English, history, religion: As long as you'd done the reading and had an opinion- any opinion—you were on solid ground. Let's not even mention psych and socie. This is why (I've always figured) the arts were heavier in guts than were the sciences, "Stars" and "Oceans" exceptions noted.

But Peter Bien had spent his life reading and contemplating Joyce and Kazantzakis, and knew what was what. I realized this immediately upon reading his comments on my "Stephen and God" paper. His points were astute and valid—dammit. His critique finished with the grade, and when I saw the C- whatever, I figured I was in deep trouble. Going in, I had assumed Joyce would be my meat, even if Kazantzakis proved to be trouble. Well, Joyce had brought me a cropper, and now, I realized, I had to produce on Kazantzakis. I had to produce, moreover, for a guy who was not only a taskmaster but also a renowned translator of Kazantzakis.

In some courses that I took at Dartmouth, I suspected certain volumes were on the assigned-reading list to pump up the professor's book sales. Peter Bien had translated several of Kazantzakis's novels and poems, including a few of the famous ones, but only one of these was included in our reading. Bien had made his choices with care, to create proper contrasts with Joyce. Peter Bien, clearly, was not teaching the course for Peter Bien. He was teaching it for us.

I came to none of these conclusions back then, back when I was taking J and K. I was looking to pull a cat out of a bag with the Kazantzakis paper, and that was it. I was enjoying the reading—actually, I was thrilled by some of it—but mid- way through Peter Bien I realized I was trying to get past Peter Bien.

And then, with the course finished, I realized it had changed me. It had ignited a life's-too-short spark. I signed up for tougher courses. Even in summer, I read denser books. I found that I dug toughness. (Full disclosure: I also found, meantime, the film department, and so I could afford a modicum of toughness since the 01' cumulative average wasn't going to be a problem.)

And then, on to real life.

I do not argue that this has anything to do with Peter Bien, but I started to find, in my work and even in my relations with others, that I was drawn to Joycean themes, Kazantzakian philosophies. It got to the point where, 15 years out, I found myself working on a project that I thought Peter Bien, of all people, might have an opinion about. What the hell, I figured: I'll call him up. He helped. The exercise was repeated a couple years later when I was working on a larger project. He helped even more.

I had never really met the man—I was never one to participate in class, and I certainly didn't star in J and K—but this second time he suggested that we talk over lunch in New York. And so we did, on a Sunday, for several hours. I enjoyed the conversation immensely, and he professed to. He professed, as well, to remember me, but I think he was being polite. Their job is not to remember us, but to teach us.

I brought a bag of books to that lunch date. I had, by now, read the complete oeuvres of both J and K, and by haunting the Strand Bookstore I'd been able to pickup some Kazantzakis first editions. As Professor Bien and I wrapped our discussions, I asked if he'd sign the books. On the title page of his translation of Report to Greco he wrote, "...after a stimulating luncheon discussing Kazantzakis and Jesus..." In his translation of SaintFrancis he wrote, "...who will appreciate that Francis is the quintessential 'follower' of Jesus—and therefore a model for all of us...." And in his translation of The Last Temptation ofChrist, he got personal: "...who did what a professor dreams about—read unassigned books after the class."

They weren't unassigned. After having been exposed to the teaching of Peter Bien, a professor who stood for rigor when it wasn't de rigueur in Hanover—and who thereby shored up one aspect of what makes Dartmouth Dartmouth—after having been exposed to that kind of teaching, anyone would consider those books required. I'll bet Don's read them.

The "Gentleman's B" has never been a part of Peter Bien's playbook.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

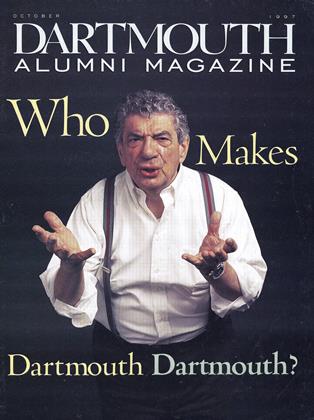

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

October 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

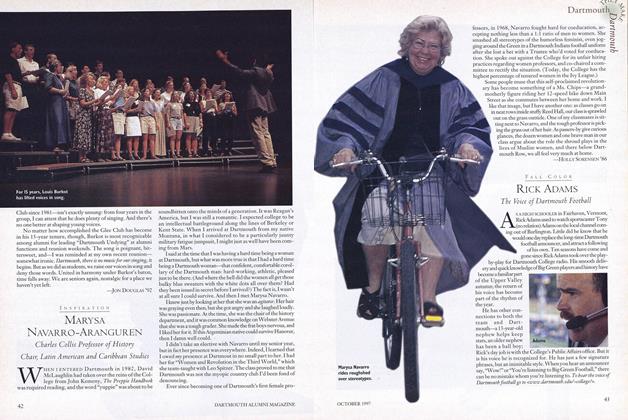

Cover StoryMarysa Navarro-Aranguren

October 1997 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Cover Story

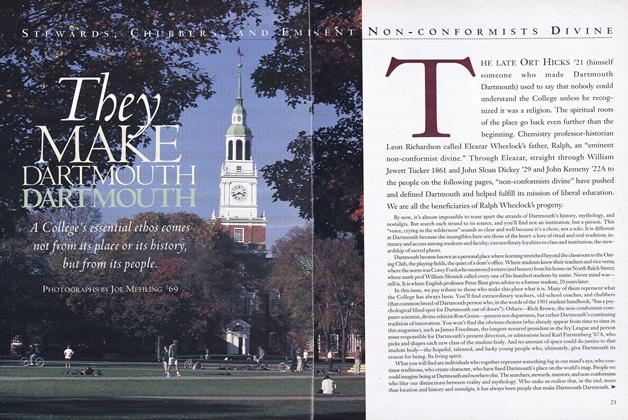

Cover StoryThey Make Dartmouth Dartmouth

October 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWilliam Cook

October 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

October 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth Dogs

October 1997 By Robert Nutt '49

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Cover Story

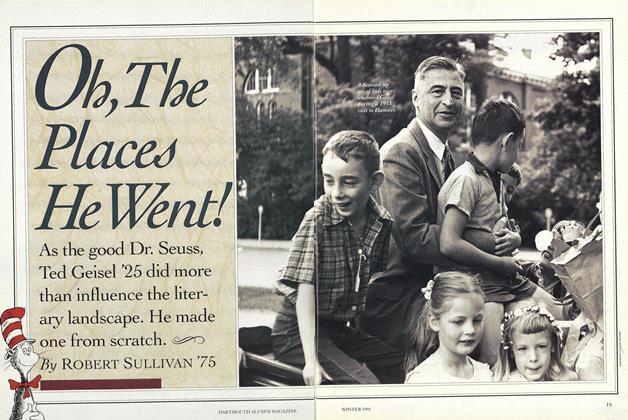

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

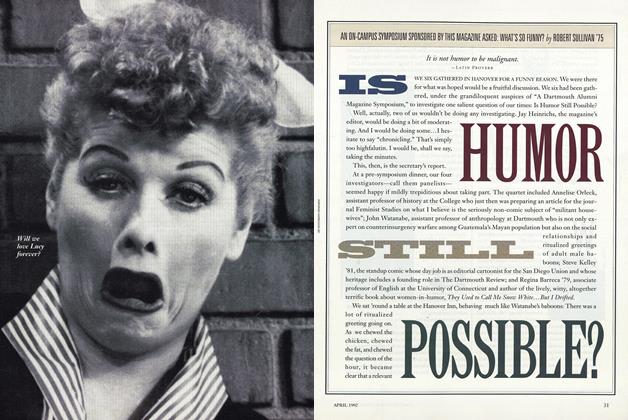

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

APRIL 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Article

ArticlePosthu-Mously, Norman Maclean Takes On a New Element

February 1993 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

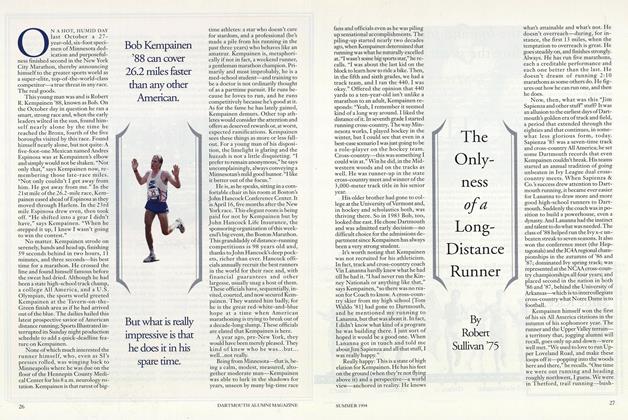

FeatureThe Onlyness of a Long-Distance Runner

June 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

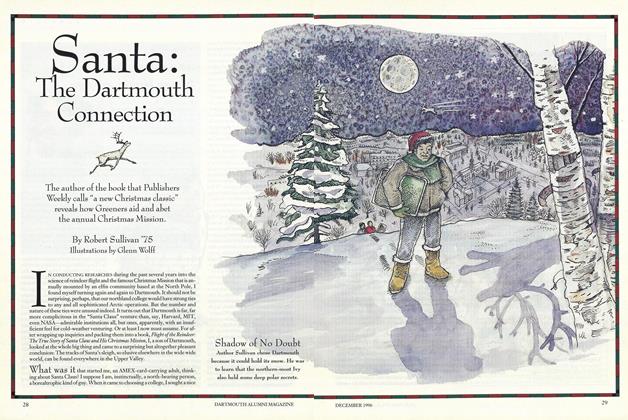

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

DECEMBER 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

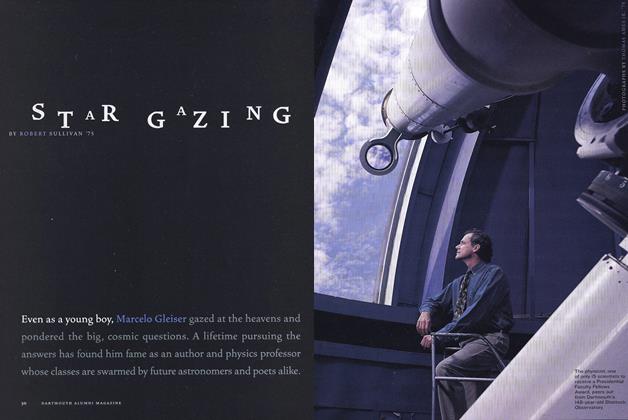

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July/Aug 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75