Give in to life 's repetition, says the Nobel laureate to the Dartmouth graduates.

Editor's Note: It may seem audacious to publish this address by Joseph Brodsky to the class of 1989. For one thing, we don t ordinarily run commencement speeches, which too often contain more pomp than circumstance. What is more, this particular address is about that most unappealing of subjects, boredom. But Brodsky is no ordinary speaker; his work earned him the 1987 Nobel Prize for literature, and his book of essays, Less Than One, has been justly acclaimed as a tour de force of criticism, philosophy, and human understanding.

But should you fail to keep your kingdom

And, like your father before you come

Where thought accuses and feeling mocks,

Believe your pain. . . . W. H. Auden

"Alonso to Ferdinand"

A substantial part of what lies ahead of you is going to be claimed by boredom. The reason I'd like to talk to you about it today, on this lofty occasion, is that I believe no liberal arts college prepares you for that eventuality; Dartmouth is no exception. Neither humanities nor science offers courses in boredom. At best, they may acquaint you with the sensation by incurring it. But what is a casual contact to an incurable malaise? The worst monotonous drone coming from a lectern or the eye-splitting textbook in turgid English is nothing in comparison to the psychological Sahara that starts right in your bedroom and spurns the horizon.

Known under several aliases—anguish, ennui, tedium, doldrums, humdrum, the blahs, apathy, lisdessness, stolidity, lethargy, languor, etc. boredom is a complex phenomenon and by and large a product of repetition. It would seem, then, that the best remedy against it would be constant inventiveness and originality. That is what you, young and new-fangled, would hope for. Alas, life won't supply you with that option, for life's main medium is precisely repetition.

One may argue, of course, that repeated attempts at originality and inventiveness are the vehicle of progress and—in the same breath—civilization. As benefits of hindsight go, however, this one is not the most valuable. For if we divide the history of our species by scientific discoveries, not to mention ethical concepts, the result will be not in our favor. We'll get, technically speaking, centuries of boredom. The very notion of originality or innovation spells out the monotony of standard reality, of life, whose main medium nay, idiom is routine.

In that, it life differs from art, whose worst enemy, as you probably know, is cliche. Small wonder, then, that art too fails to instruct you as to how to handle boredom. There are few novels about this subject; paintings are still fewer; and as for music, it is largely non-semantic. On the whole, art treats boredom in a self-defensive, satirical fashion. The only way art can become for you a solace from boredom, from the existential equivalent of cliche, is if you yourselves become artists. Given your number, though, this prospect is as unappetizing as it is unlikely.

But even should you march out of this commencement in full force to typewriters, easels and Steinway grands, you won't shield yourselves from boredom entirely. If repetitiveness is boredom's mother, you, young and new-fangled, will be quickly smothered by lack of recognition and low pay, both chronic in the world of art. In these respects, writing, painting, composing music are plain inferior to working for a law firm, a bank, or even a lab.

Herein, of course, lies art's saving grace. Not being lucrative, it falls victim to demography rather reluctantly. For if, as we've said, repetition is boredom's mother, demography (which is to play in your lives a far greater role than any discipline you've mastered here) is its other parent. This may sound misanthropic to you, but I am more than twice your age, and I have lived to see the population of our globe double. By the time you're my age, it will have quadrupled, and not exactly in the fashion you expect. For instance, by the year 2000, there is going to be such cultural and ethnic rearrangement as to challenge your notion of your own humanity.

That alone will reduce the prospects of originality and inventiveness as antidotes to boredom. But even in a more monochromatic world, the other trouble with originality and inventiveness is precisely that they literally pay off. Provided that you are capable of either, you will become well off rather fast. Desirable as that may be, most of you know first hand that nobody is as bored as the rich, for money buys time, and time is repetitive. Assuming that you are not heading for poverty—for otherwise you wouldn't have entered college one can expect your being hit by boredom as soon as the first tools of self-gratification become available to you.

Thanks to modern technology, those tools are as numerous as boredom's synonyms. In light of their function to render you oblivious to the redundancy of time their abundance is revealing. Equally revealing is the function of your purchasing power toward whose increase you'll walk out of this commencement ground through the click and whirr of some of those instruments tightly held by your parents and relatives. It is a prophetic scene, ladies and gentlemen of the class of 1989, for you are entering the world where recording an event dwarfs the event itself the world of video, stereo, remote control, jogging suit and exercise machine to keep you fit for reliving your own or someone else's past: canned ecstasy claiming raw flesh.

Everything that displays a pattern is pregnant with boredom. That applies to money in more ways than one, both to the banknotes as such and to the possessing of them. That is not to bill poverty, of course, as an escape from boredom although St. Francis, it would seem, has managed exactly that. Yet for all the deprivation surrounding us, the idea of new monastic orders doesn't appear particular catchy in this era of video-Christianity. Besides, young and new-fangled, you are more eager to do good in some South Africa or other than next door, keener on giving up your favorite brand of soda than on venturing to the wrong side of the tracks. So nobody advises poverty for you. All one can suggest is to be a bit more apprehensive of money, for the zeros in your accounts may usher in their mental equivalents.

As for poverty, boredom is the most brutal part of its misery, and the departure from it takes more radical forms: of violent rebellion or drug addiction. Both are temporary, for the misery of poverty is infinite; both, because of that infinity, are costly In general, a man shooting heroin into his vein does so largely for the same reason you buy a video: to dodge the redundancy of time. The difference, though, is that he spends more than he's got, and that his means of escaping become as redundant as what he is escaping from faster than yours. On the whole, the difference in tactility between a syringe's needle and a stereo's push-button roughly corresponds to that between the acuteness and dullness of time's impact upon the have-nots and the haves. In short, whether rich or poor, sooner or later you will be afflicted by this redundance of time.

Potential haves, you'll be bored with your work, your friends, your spouses, your lovers, the view from your window, the furniture or wallpaper in your room, your thoughts, yourselves. Accordingly, you'll try to devise ways of escape. Apart from the self-gratifying gadgets mentioned before, you may take up changing jobs, residence, company, country, climate; you may take up promiscuity, alcohol, travel, cooking lessons, drugs, psychoanalysis.

In fact, you may lump all these together; and for a while that may work. Until the day, of course, when you wake up in your bedroom amidst a new family and a different wallpaper, in a different- state and climate, with a heap of bills from your travel agent and your shrink, yet with the same stale feeling toward the light of day pouring through your window. You'll put on your loafers only to discover they're lacking bootstraps to lift yourself by out of what you recognize. Depending on your temperament or the age you are at, you will either panic or resign yourself to the familiarity of the sensation; or else you'll go through the rigamarole of change once more.

Neurosis and depression will enter your lexicon, pills your medical cabinet. Basically, there is nothing wrong about turning life into the constant quest for alternatives, into leapfrogging jobs, spouses, surroundings, etc., provided you can afford the alimony and jumbled memories. This predicament, after all, has been sufficiently glamorized on screen and in Romantic poetry. The rub, however, is that before long this quest turns into a full-time occupation, with your need for an alternative coming to match a drug addict's daily fix.

There is yet another way out of it, however. Not a better one, perhaps, from your point of view, and not necessarily secure, but straight and inexpensive. Those of you who have read Robert Frost's "Servant to Servants" may remember a line of his, "The best way out is always through." So what I am about to suggest is a variation on the theme.

When hit by boredom, go for it. Let yourself be crushed by it; submerge, hit the bottom. In general, with things unpleasant, the rule is the sooner you hit the bottom, the faster you surface. The idea here, to paraphrase another great poet of the English language, is to exact fall look at the worst. The reason boredom deserves such scrutiny is that it represents pure, undiluted time in all its repetitive, redundant, monotonous splendor.

In a manner of speaking, boredom is your window on time, on those properties of it one tends to ignore to the likely peril of one's mental equilibrium. In short, it is your window onto time's infinity, which is to say on your insignificance in it. That's what accounts, perhaps, for one's dread of lonely, torpid evenings, for the fascination with which one watches sometimes a fleck of dust aswirl in a sunbeam, and somewhere a clock ticktocks, the day is hot, and your willpower is at a zero.

Once this window opens, don't tryto shut it; on the contrary, throw it wide open. For boredom speaks the language of time, and it is to teach you the most valuable lesson in your life the one you didn't get here, on these green lawns the lesson of your utter insignificance. It is valuable to you, as well as to those you are to rub shoulders with. "You are finite," time tells you in a voice of boredom, "and what-ever you do is, from my point of view, futile." As music to your ears, this, of course, may not count; yet the sense of futility, of limited significance even of your best, most ardent actions is better than the illusion of their consequences and the attendant self-aggrandizement.

For boredom is an invasion of time into your set of values. It puts your existence into its perspective, the net result of which is precision and humility. The former, it must be noted, breeds the latter. The more you learn about your own size, the more humble and the more compassionate you become to your likes, to that dust aswirl in a sunbeam or already immobile atop your table. Ah, how much life went into those flecks! Not from your point of view but from theirs. You are to them what time is to you; that's why they look so small. And do you know what the dust says when it's being wiped off the table?

"Remember me," says the dust.

I've quoted it not because I'd like to instill in you affinity for things small seeds and plants, grains of sand or mosquitoes small but numerous. I've quoted these lines because I like them, because I recognize in them myself, and for that matter any living organism to be wiped off from the available surface. "Remember me," says the dust. And one hears in this that if we learn about ourselves from time, perhaps time, in turn, may learn something from us. What would that be? That inferior in significance, we best it in sensitivity.

This is what it means to be insignificant. If it takes will-paralyzing boredom to bring this home, then hail the boredom. You are insignificant because you are finite. Yet the more finite a thing is, the more it is charged with life, emotions, joy, fears, compassion. For infinity is not terribly lively, not terribly emotional. Your boredom, at least, tells you that much. Because your boredom is the boredom of infinity.

Respect it, then, for its origins as much perhaps as for your own. Because it is the anticipation of that inanimate infinity that accounts for the intensity of human sentiments, often resulting in a conception of a new life. This is not to say that you have been conceived out of boredom, or that the finite breeds the finite (though both may ring true). It is to suggest, rather, that passion is the privilege of the insignificant.

So try to stay passionate, leave your cool to constellations. Passion, above all, is a remedy against boredom. Another one, of course, is pain—physical more so than psychological, passion's frequent aftermath; although I wish you neither. Still, when you hurt you know that at least you haven't been deceived (by your body or by your psyche). By the same token, what's good about boredom, about anguish and the sense of the meaninglessness of your own, of everything else's existence, is that it is not a deception.

If you find all this gloomy, you don't know what gloom is. If you find this irrelevant, I hope time will prove you right. Should you find this inappropriate for such a lofty occasion, I will disagree.

I would agree with you had this occasion been celebrating your staying here; but it marks your departure. By tomorrow you'll be out of here since your parents paid only for four years, not a day longer. So you must go elsewhere, to make your careers, money, families, to meet your unique fates. And as for that elsewhere, neither among stars and in the tropics nor across the border in Vermont is there much awareness of this ceremony on the Dartmouth Green. One wouldn't even bet the sound of your band reaches White River Junction.

You are exiting this place, members of the class of 1989. You are entering the world, which is going to be far more thickly settled than this neck of the woods and where you'll be paid far less attention than you have been used to for the last four years. You are on your own in a big way. Speaking of your significance, you can quickly estimate it by pitting your eleven hundred to the world's 4.9 billion. Prudence, then, is as appropriate on this occasion as is fanfare.

I wish you nothing but happiness. Still there are going to be plenty of dark and, what's worse, dull hours, caused as much by the world outside as by your own minds. You ought to be fortified against that in some fashion; and that's what I've tried to do here in my feeble way, although that's obviously not enough.

For what lies ahead is a remarkable but wearisome journey; you are boarding today, as it were, a runaway train. No one can tell you what lies ahead, least of all those who remain behind. One thing, however, they can assure you of is that it's not a round-trip. Try therefore to derive some comfort from the notion that no matter how unpalatable this or that station may turn out to be, the train doesn't stop there for good. Therefore, you are never stuck—not even when you feel you are for this place, today it becomes your past. From now on, it will be only receding for you, for that train is in a constant motion. It will be receding for you even when you feel that you are stuck

... So take one last look at it, while it is still its normal size, while it is not yet a photograph. Look at it with all the tenderness you can muster, for you are looking at your past. Exact, as it were, the full look at the best. For I doubt you'll ever have it better than here.

"RED CELIA" BY DAVID HOCKNEY. Hood Museum of Art. Purchased through the William S. Rubin Fund, and the Miriam and Sydney Stoneman Acquisitions Fund

"ZEN FOR TV" BY NAM JUNE PAIK. Hood Museum of Art

"SUPPER" BY ALEX KATZ. Hood Museum of Art. Gift of Joachim Jean Aberbach

"HELLO AND GOOD-BYE" BY ALLAN D'ARCANGELO. Hood Museum of Art. Gift of Howard Zagor '40 and Mrs. Zagor

"By the year 2000,there is going to besuch cultural andethnic rearrangementas to challenge yournotion of your ownhumanity."

"The reason boredomdeserves such scrutinyis that it representspure, undiluted timein all its repetitive,redundant,monotonoussplendor."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDon't Call It "The D"

October 1989 By Michael T. Reynolds '90 -

Feature

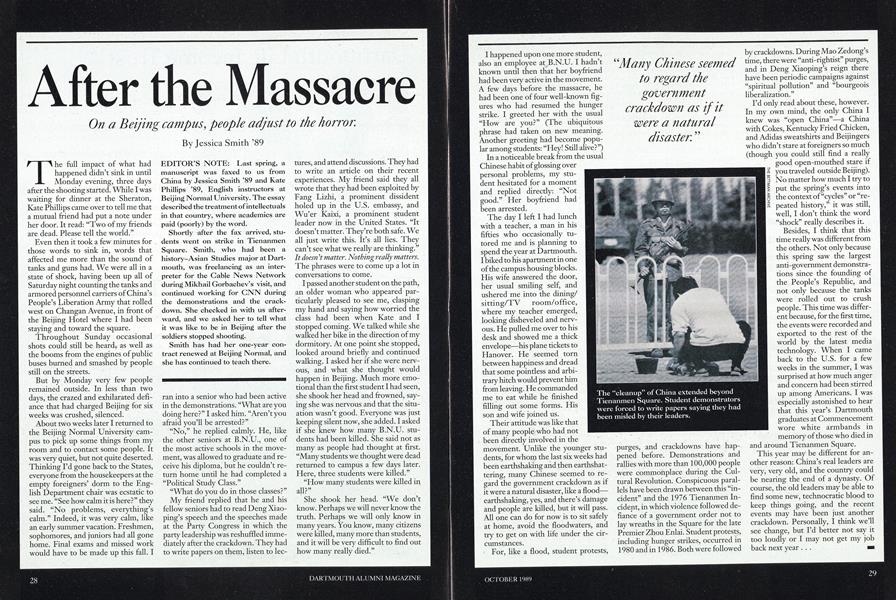

FeatureAfter the Massacre

October 1989 By Jessica Smith '89 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureBUBBLE AND PEAK

October 1989 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1989 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth Honors an Increasingly Rare Species: the Dedicated Coach

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureENGINEERING SCIENCE

May 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Report

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 -

Feature

FeaturePREFACE TO DARTMOUTH

December 1954 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62 -

Feature

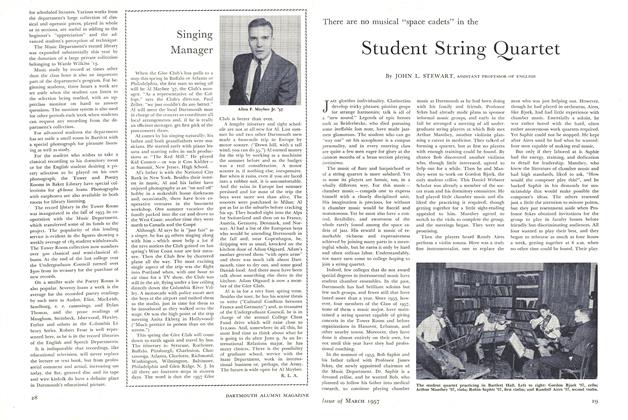

FeatureStudent String Quartet

March 1957 By JOHN L. STEWART -

Feature

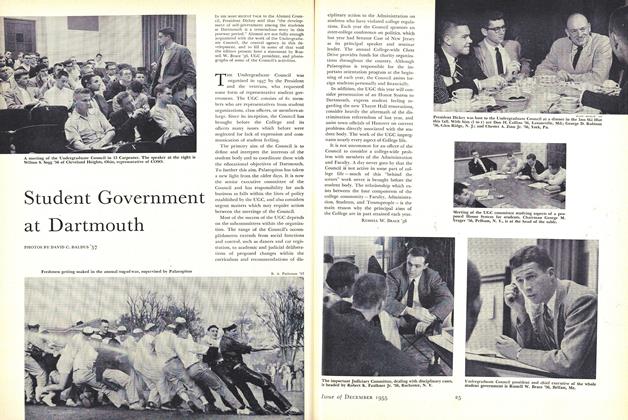

FeatureStudent Government at Dartmouth

December 1955 By RUSSELL W. BRACE '56