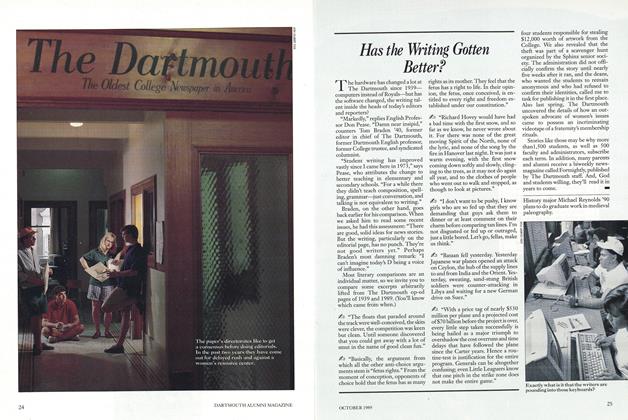

Nor, after 50 years of independence, is The Dartmouth the "Parkhurst Pravda."

The trouble had started even before The Dartmouth's editor in chief wrote an editorial likening alumni reunions to "an Elks convention." Ever since Budd Schulberg '36 was editor, the paper had been stirring things up by publishing leftwing opinions and maddeningly revealing investigative stories. And then, in June of 1938, Editor-in-Chief O'Brien Boldt '39 attacked reunions in a piece titled "The Alumni Circus," which observed that Dartmouth's graduates "seem out of touch with the College."

Boldt's editorials had already been annoying President Hopkins, who was himself a former editor in chief, but now some people thought this was going too far. A committee of alumni and administrators urged the president to place an alumni trustee in charge of the newspaper.

"We got a kick out of it all," O'Brien Boldt recalls of the fuss over his editorial. "To us, reuning alumni looked like idiots who only cared about drinking and football. We thought, 'These are the same guys who are pressuring the administration to change things on campus? Now a freelance writer with a Ph.D. in political science, Boldt missed his own class's 50th reunion this past summer.

Thanks in part to Boldt's untactful remarks about alumni, a half-century later The Dartmouth (the editors detest calling it by its belittling initial) enjoys a degree of freedom that, while underrated, Occasionally unnerves some College administrators. As the editor in chief of the paper a halfcentury after its celebrated independence battle, I have often wondered what forces have influenced my predecessors—many of whom have taken advantage of The Dartmouth's separate identity to swim noisily against the campus's traditional conservativism.

In fact, over the past five decades The Dartmouth has weathered a reputation as a bastion of liberal thought. The paper advocated the eradication of racial clauses in fraternities before the issue had reached the forefront of national attention. In the 1960s The Dartmouth made a strong call for coeducation nearly a decade before the actual admission of women. In the past two years, the paper has endorsed delayed rush, denounced the use of women as hostesses at fraternity formal rush and called for an end to secret senior societies.

One of the paper's best-known liberal editors took over from the 1939 crusaders. A junior from Dubuque, lowa, Tom Braden '40 went on to become a nationally syndicated columnist, a Dartmouth trustee and a jouster with the arch conservative Patrick Buchanan on Cable News Network's "Crossfire" program. Braden attributes his selection as Dartmouth editor in part to the terrible hurricane of 1938, which leveled many of the campus's ancient elms and wiped out the editorial office's electricity. Committed to the ideal of a daily paper being daily at all costs, Braden gathered candles and flashlights and set the type himself on a hand-cranked flatbed proof press. He ran off nearly 3,000 copies of the newspaper before 9 in the mornings went to bed, and cut classes for the day. The editors were amazed.

Like his predecessors, Braden advocated isolationism from the conflict in Europe. He soon regretted it. After graduation—before the United States had officially declared war—he joined the British army and served under Montgomery in Africa, transferring to American forces in 1943. Today he glances at pictures of friends at The Dartmouth on the wall of his home office and says, "If it hadn't been for The Dartmouth I wouldn't be where I am now."

When Jerry Tallmer '42 took over, The Dartmouth changed its stance on Europe, becoming one of the nation's first interventionist college newspapers. Tallmer remembers the earlyl940s as a time when "everything was a controversy." In the spring of 1941, the paper ran a front-page open letter to President Roosevelt by Charles Bolte '41, who called for the United States to enter the war. "The editorial tore the whole campus apart," recalls Tallmer. "It was as intense as Vietnam and the race issue today." One of the founders of the Village Voice, Tallmer has spent the past 20 years as a reporter and critic at the New York Post.

The paper's liberalism caught up to it at the onset of the McCarthy era, when John Stearns '49, a self-described "confused liberal" in college, became editor. He characterizes his tenure as a time when the paper tried to present the opposing view to an institution that was "99 percent Republican. We were the red-rag, liberal-liberal types," he says. Stearns's successor, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Frank Gilroy '50, recalls the "red-rag" label, but he also remembers the paper being called a "fascist sheet." Such divergent commentaries convinced Gilroy that the editors "must have been doing about right." Nonetheless, their zeal in promoting causes bothered Ken Roman '52. When he took over, he committed his directorate to the ideal of an "open newspaper" that would "represent all points of view."

Even when it makes such a noble attempt, however, for almost 200 years The Dartmouth has walked a thin line between its journalistic mission and its closeness to the College. It can call for removal of an occasional dean, but it has to be nice about it. William Hartley '58, an anchor for CNN, describes the dilemma during his time as editor in chief: "We were independent, but we were a part of the College. We were within the sphere of the College." It is academia's version of the small-town paper.

Still, few former editors recall attempts by the administration to censor material. One of those few, Mort Kondracke '60, relays the story of how his directorate bowed to the wishes of Dean Thaddeus Seymour to avoid covering two all-College meetings. Seymour used the meetings to lecture students about a young Hanover girl who "was servicing or being victimized by" Dartmouth men, according to Kondracke. Currently senior editor of the New Republic, Kondracke recalls that Seymour wanted to avoid tipping off the national press. Only one sentence from the meetings appeared in The Dartmouth, on the front page of the February 2, 1960, edition: "We often think of Dartmouth as a kind of snow-capped Fiji island." The quote was attributed to Seymour. If Kondracke were editor today, he says, he probably would have ignored the dean's request. But journalistic mores have changed. "It was a completely different atmosphere," he explains, "with social rules in dorms and kids who tended to be more docile. Even the national press did not report the goings-on in the White House."

The vocal editors of the late 1960s felt comfortable speaking their minds, but they almost lost the ability to put their ideas on paper. When for business reasons The Dartmouth's printer refused to publish the newspaper and no other printer could be found, the 1967 directorate asked President Dickey if he knew what they could do. Editor-in-Chief William Green '68 recalls Dickey's suggestion that the editors mimeograph the paper each day Unsatisfied with this advice, Green and Business Manager Chuck Schader '68 took the costly step of purchasing a press and a linotyper, which they installed in a rented space off Main Street. The paper missed some deadlines as a result, but it could boast being one of only a handful of college newspapers with its own press.

The machine was not the only thing the 1967 directorate brought to Dartmouth. The paper also invited Alabama Governor George Wallace to speak at Webster Hall. "We did it because Dartmouth was boring," Green explains. Since the administration had not invited Wallace, it refused to provide security and other essential help. So The Dartmouth arranged student security and supervision. Hours before the governor's arrival, Green remembers a conversation in front of Webster between Wallace aides and College Proctor John O' Connor. When asked by the aides if a riot could ensue, O'Connor replied, "You could have the Last Supper re-enacted on this campus with the original cast and no one would notice .... Dartmouth students do not riot." The proctor had misjudged the situation. During the governor's speech, students stormed the stage and forced him to leave it. Wallace returned to the stage and received an ovation. But as he drove away from Webster Hall, students attacked his car with their fists.

The memory of the incident does not sour Green's feeling for his time at the paper. Chairman of the religion and classics department at the University of Rochester, Green says he owes a great deal to his undergraduate journalism. "I learned more for the rest of my life from the paper than from any classroom," he asserts.

Paul Gigot '77 also found his stint as editor in chief to be educationalhe maintains that The Dartmouth was a better training ground than journalism school. Though characterizing his tenure as "not terribly politically active," Gigot recalls being the only conservative on a seven-member editorial board which endorsed Jimmy Carter for the presidency ("one of our more ill-advised decisions," he says). Gigot is now a Washington columnist and editorial board member of The Wall Street Journal.

Gigot was hardly the last conservative to serve with The Dartmouth. In 1980, a schism within the directorate led Editor-in-Chief Greg Fossedal '8l to leave the paper and start the conservative Dartmouth Review. Other staffers joined him, including Keeney Jones '82 and cartoonist Steve Kelly '81 who now draws for the San Diego Union.

"It was hard for people from different camps to communicate," recalls Marie Center '82, who became the paper's second woman to serve as chief editor. (Anne Bagamery '78 was the first, and Center was followed by Karen Garnett 'B6 and Jamie Heller '89.) In the midst of a deeply divided campus, during the 1980s The Dartmouth began to take flak for being the administration's mouthpiece the "Parkhurst Pravda," as the Review gleefully put it.

These comments never cease to amaze me when I think of all the stories I published which would never have seen the the printer's ink if a College administrator had had any say in the matter. I would guess that administrators were not particularly thrilled that The Dartmouth revealed the salaries of the highest paid College employees or released the names of the honorary-degree recipients nearly one month before the scheduled official announcement.

As a registered Republican who supported Reagan and Bush, I am likewise surprised by claims that the newspaper is controlled by leftists. It is true that the previous two directorates were predominandy Democratic. But in 1988 it ran an editorial against the proposed Woman's Resource Center—a column that attracted the fury of feminists. The editors I work with are more interested in news than polemics. One of our proudest moments was a story we published in late spring, after nearly a month of sleuthing by a team of reporters and editors. The article revealed the identities of

Early Dartmouth editors like this 1881 group were as much literary as journalistic. The muckraking didn't begin until the 1930s.

The current editors like to think their past is hoarier than anyone else's. Chief Reynolds is to the left of the TV.

Former Editor O'Brien Boldt '39, looking over today's newsroom, recalls how he likened reunions to a circus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBoredom's Uses

October 1989 By Joseph Brodsky -

Feature

FeatureAfter the Massacre

October 1989 By Jessica Smith '89 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureBUBBLE AND PEAK

October 1989 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1989 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth Honors an Increasingly Rare Species: the Dedicated Coach

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Cover Story

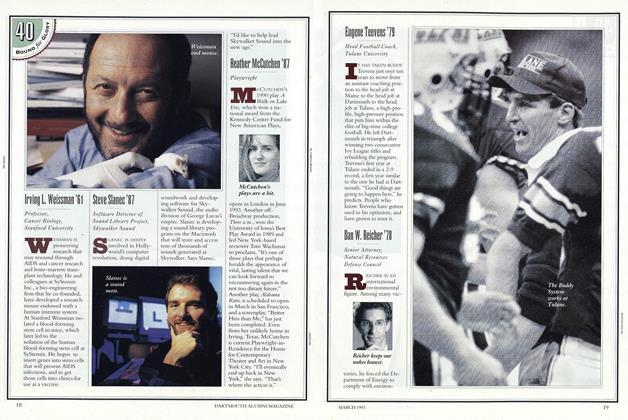

Cover StoryDan W. Reicher '78

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureTIMOTHY WAS BEFORE YOU

June 1955 By DANIEL CHASE '14 -

Cover Story

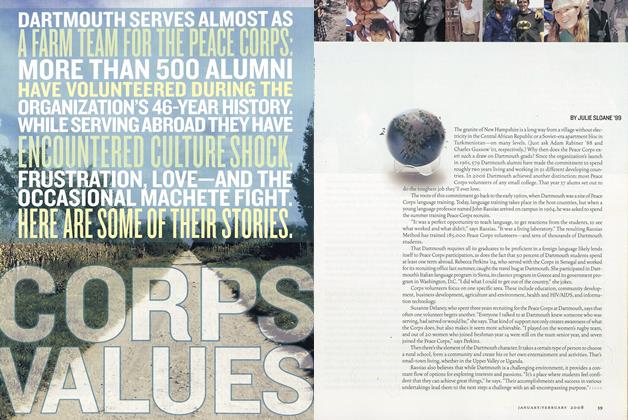

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

FeatureA Look Backward and A Look Ahead

JULY 1964 By MICHAEL JAY LANDAY '64