Amid memories of terror come times thatremind us what life is for.

MEN OF DARTMOUTH SERVED IN COUNTLESS ways in World War II. Many of their stories have been told in the 50 years since the war: of the 234 Dartmouth men who didn't come back, the hardships

We don't often pause to hear of war's other side, the gentle lulls that come when least expected. These are moments of peace, a cloud traversing' the sky. Rare and delicate, such moments are reminders of the beauty of life and of what is at stake during war.

As the 50th anniversary of the end of the war passes into history, we pause to hear how nine Dartmouth veterans found unforgettable interludes.

Taste of Home

Wilbur Johnson '44, an infantry captain who ached to fly, transferred to the Army Air Corps and learned to fly a P-47 Thunderbolt. He was attached to the 27th Fighter-Bomber Group between Florence and Pisa. He flew his 23 rd mission, a ran to bomb rail yards in the town of Trento on February 8,1945. It was his last. Shot down, he was hidden from the Germans for a month by the residents of the Italian village of Bione, then captured and sent to a prison camp in Nuremberg. Marched 90 miles to another camp in Mooseburg, he and his column were strafed by six Thunderbolts.

"My most peaceful memory came on April 29, 1945. It was the day! was liberated from Stalag VII A by General Patton's Third Army. Patton himself entered the camp riding a half-track, with his pearl-handled pistols and a chrome-plated helmet. We were served fresh doughnuts and some chewing gum by the American Red Cross. Those doughnuts tasted like cake, I'll tell you. We had been sustained by these parcels we got once a week from the American Red Cross that contained cigarettes, coffee, flour, sugar, and cocoa. And the Germans gave us dark bread, sauerkraut, potato soup, and bean soup, with a bug in each bean.

"But I have never tasted anything quite like those doughnuts."

Luck

James White '44 was a first lieutenant with the 319th fighter squadron of the 325th fighter group based in Rimini, Italy. On March 18, 1945, during his 58th mission, the P-51 Mustang he was piloting was shot down over a German airfield in Hungary.

"It wasn't exactly peaceful, but I knew I'd spend the rest of my time in a POW camp, so for me the war was pretty much over. You could say it was peaceful just lying around Stalag 17, chatting with the other fellows. My legs were stiff because of my burns, so there wasn't much I could do but talk.

"When I got shot down, I was being pursued by two Messerschmitts when I got hit at about 1,500 feet. My plane caught fire and my legs were burned, so I bailed out. I came down in some trees, and one of the pilots who shot me down said he saw my 'chute. So they came looking for me, and an SS guy took me back to a guardhouse where the two pilots I was fighting with were waiting for me, so I knew my burns would be taken care of. They were in their leathers, and one of them, a captain named Helmut Lipfert, was ranting at me. The SS guy, who spoke English, told me he was saying I was lucky. It turns out his guns jammed. I later learned Lipfert had 205 victories in aerial duels.

"The other pilot is the one who got the credit for shooting me down. His name is Peter Esser. In 1990, Esser contacted me. He wanted to see what I had done in life. He had my escape photo and knew my plane had a checkered tail, so he had enough information to track me down. He's an awfully sweet guy, really ebullient. I spent ten days in Meckenheim with him. I stayed in a building he owns, and he'd come pick me up every day and we'd go touring around. One day we went up in a hot air balloon with a friend of his who was also a Messerschmitt pilot.

"The town he was from was flattened by a Marauder [B-26] raid. And his father-in-law was killed when a passenger train he was riding on was strafed, presumably by a P-47. He took a single bullet in the head. It made Peter, and most Germans, I think, a firm believer in peace. War doesn't help so ve anything.

"I never flew after the war."

Solitude

Everett Wood '38 was a lieutenant junior grade with VP-84, an anti-submarine squadron stationed in Reykjavik, Iceland. He piloted a PBY, a large, boat-like plane used to cover the convoys that were being preyed upon by German U-boats. Wood had been on the Dartmouth ski team and spent much of his free time in the North Atlantic dreaming of skiing. For two days in the middle of the war, he got to do more than dream about it.

"This particular outing took place in the middle of April, 1943. It had been a very tough winter, during the Battle of the Atlantic. The Germans were throwing everything at us. We got a two-day holiday and six of us, four Icelanders and two Americans—one of the Icelanders, Bjorn Blondal, was the finest skier in the country—got an old truck and drove 30 miles east of Reykjavik into the mountains. We stayed at an old hut and slept on the floor and had perfect snow and solitude and the first salmon of the season. My future wife, Nunna Jonsdottir, worked for a fishing company and brought the salmon, a 12-pound beauty.

"For two days we didn't see another human being. The only living thing we saw were two coveys of ptarmigan. It was perfect corn snow. Not a cloud in the sky and no wind at all. It was enough to make even a bad skier think he's pretty good. Bjorn's sister Inge was a great musician and we sang, teaching each other different songs. Believe it or not, one of them was a German song, 'Muss i denn,' 'Must I leave this little town...' We brought some whisky and some aquavit, because we were pilots. We laughed a lot.

"It was a wonderful moment. And after living in a Quonset hut, the sense of solitude was wonderful."

R & R

Stan Zarod '44 was in the Marines for four years, and fought the batdes for Guadalcanal, Okinawa, and some smaller engagements in the Solomons. Zarod, who played for the Dodgers after the war, says he would rather not disclose his rank: "It went up and down a lot."

"There were no peaceful moments, dayto-day. Even when you had an island se- cured, every so often you'd get a sniper who would start shooting.

"I do remember coming back to Guam after the battle for Okinawa was over. We were in rest camp for a couple of months, getting ready for the invasion of Japan. We had liberty at all times. There were outdoor movies, the first ones I had seen in two years, and I played some baseball and some basketball with the boys. And I had my first taste of ice cream in years. I met a friend from Ludlow [Vermont] who was in the Seabees, and he said 'How'd you like some ice cream?' He gave me a gallon of it. It was made from powdered milk, of course, so it wasn't so great, but it tasted pretty good.

"I didn't have much. I took it back and shared it with the boys. We all had a taste."

A Good Vintage

Walker Weed '40 was an infantry officer with the Tenth Mountain Division. After extensive training in Colorado, California, and Alaska, the Tenth was sent into Italy to fight its way through up the Po Valley and into the Italian Alps. "There were a lot of Dartmouth guys in the Tenth because they wanted guys who could ski and were at home in the mountains," he says.

"What I was thinking about happened right after the war in Europe ended but before things really settled down. And it is this: Sitting on the bottom of Italy's Lake Garda with two cases of Piper-Heidsieck '28.1 discovered that that was a very good vintage. We had a considerable amount of the stuff available after we had captured, I mean liberated, some German stores. They destroyed a lot of stuff as they retreated but not the Piper-Heidsieck. Sometimes we made mint juleps with catnip, too. Anyway, we'd take the champagne down to the bottom of the lake and let it chill while we went for a swim, then come back and drinkit. It was wonderful."

Touch of Class

Dave Scottford '44 was an Army Air Corp pilot of a P-51 Mustang based on Iwo Jima. He flew nine long-range missions of seven hours-plus as air support to bombers attacking the Japanese mainland, and ten or 12 short missions to nearby islands. He served from January 1943 to November 1945.

"I went to a string quartet concert on Iwo Jima. The USO brought them over. I can't remember their name, but they were well known, a woman and three men. They had quite a large audience, although most people there had never seen such a thing and I doubt had much of an interest in classical music. But they listened attentively and were quite respectful. That was probably because there was a woman there. We didn't see many women. Even still, it was a very calm and soothing event. The woman and maybe the men—I don't really remember the men—came over to the officers club, and we talked to her about what we were doing. We hadn't cleaned up our language because we hadn't seen a woman in so long. It would seem pretty mild now, but it just slipped out back then."

Friends and Lovers

Alex Fanelli '42 drove from Hanover to Boston to enlist with Jerry Tallmer '42 a few days after thejapanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The Army Air Corps—the only branch of the service that would take the nearsighted editors ofThe Dartmouthsent them together to radio school, then radar school. Both were stationed in the Caribbean, where they operated radar on B-18s that flew air cover for convoys and hunted German submarines. Later, Fanelli helped set up a school for B-29 radar operators at Alamagordo Air Base in New Mexico.

"My service was absolutely non-threatening. We flew long missions, eight or nine hours, out of our base on Aruba and would do figure eights over the convoys. We were shot at once by a sub we caught on the surface, but that was it.

"One particular day, we were flying back to Aruba and I was operating the radio, listening to other planes. I heard, in Morse Code, a guy sign off and I thought, 'That sounds just like Jerry Tallmer.' There's a way you can tell who the operator is by listening for a unique sound the operator has. And besides, he and I had practiced quite a bit together. Sol broke in and hit I-N-T, which means I'm asking a question, then J- Tand he came back with R, for received, then Correct, Correct,Correct. It was him! So we had a conversation and caught up on things. It was very satisfying to pick that out of all those signals and to hear from an old friend.

"Then, when I was at Alamagordo in New Mexico, I used to play ping-pong with a buddy of mine and he said he wanted me to play against this WAC named Betty. I was pretty good, but she won the first three games we played. I decided to ask her to marry me. When I proposed, it was not a moment of peace. We were on the parade ground and it was dark, kind of a nice evening. I had read some poetry and remembered the lines from a work by Christopher Marlowe, 'Come live with me, and be my love; and we will all the pleasures prove.' It must have been the right thing to say because she said yes. We got married in the base chapel on June 22, 1945. Those lines of poetry were later inscribed on our wedding rings. They cost five dollars, and we still have them."

Moral Focus

Clinton Gardner '44 agonized as a Dartmouth student about the moral implications of killing other humans. He considered becoming a conscientious objector. But after reading more about Hitler, Gardner enlisted and became a commander of an antiaircraft artillery battery that went ashore at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944. Nearly a year later, he became commandant of the newly liberated Buchenwald concentration camp. "I remember being completely horrified. Also, very clearly, that in order not to have a breakdown, I realized I had to be stoic. I had to freeze up," he told the Valley News. But it was at Omaha Beach that he had found his strength.

"I had been in England for about six months before DDay, and had spent a lot of time reading the Bible and reflecting on life and death and whether or not there's life after death. I didn't think so then, and I still don't, but I still went to church services a lot before the invasion, both Protestant and Catholic, just in case.

"I landed on the worst possible beach, Omaha Easy Red. I was in the fourth wave and came ashore about nine a.m. on D-Day. It was a mess. Our battery never made it, and at about six in the evening, I was hit in the head with a mortar shell. It left a hole in my helmet so big you could put both hands in it, and it stuck my helmet to my head. I couldn't take

it off. There was a lot of blood, and I couldn't talk, although I could walk. Everyone thought I was going to die, and so did I. All the medics were killed, so the guys just left me on the beach. The next day they finally moved me to a field hospital, where doctors told me the wound was just the flesh on my scalp, not my brain, and that I was going to be okay.

"So they prepared me to go back to England, and at the top of the cliff above Omaha, on the way to the boat that would take me back, looking out at all the ships on the horizon, all my religious musings and ponderings of the last few years came into a focus. It was a moment of gathering thoughts and thinking how fortunate I was to be alive when half the people who had landed in my sector had been killed or wounded. It was tran- It was peace and serenity. I looked out and the horizon seemed to expand and the colors became more intense and time and space seemed compressed. And I knew then that my decision to fight was the right one. Because if ever there was a time that it was right to fight, that was it."

Fellowship

Ted Brush '44 joined the Marine Corps on March 11,1942 and was told to go back to Hanover to finish his college education. He went on active duty in August, 1943. From then until he was discharged at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on April 6, 1946, he was a Leatherneck artillery officer. In the South Pacific, he was a forward observer in the third division of the Fleet Marine Force. "I went in with assault battalions to call down the fire from the cruisers and destroyers, our artillery, and the air strikes off carriers," he says.

"There wasn't much time during combat to think about peace. But when I came ashore on Iwo Jima, it was a pleasant surprise to see Dick Rondeau '44, the famous hockey player on Dartmouth's 1942 national hockey championship team. He was a military policeman on the beach at Iwo. That was a surprise to see him directing the beach traffic.

"Another Dartmouth buddy, Fred Campbell '44, and I went through boot camp and pretty much the whole war together. We were on Guam around the time of the invasion of Iwo Jima, and I heard thatjames Browning '44 was around. Jim and I had grown up together in Great Neck, New York, then went to Dartmouth. I knew he was a meteorologist assigned to the Air Force, but the last I had heard he was on a really small island in the middle of the Pacific.

"When I found out he was on Guam, Campbell and I went looking for him. We got in a Jeep and drove out to this very isolated spot and found a tent, and there was Jim. Now, he's a very intellectual guy and always has been, but I don't think there were many guys on Guam all by themselves in a tent, reading a book.

"He was a special guy. They all were."

"I HAVE NEVER TASTED ANYTHING QUITE LIKE THOSE DOUGHNUTS."

"PERFECT SNOW AND SOLITUDE AND THE FIRST SALMON OF THE SEASON."

"He said "How'd you like some ice cream?

"We'd take the champagne down to the bottom of the lake and let it chill while we went for a swim"

"I WENT TO A STRING QUARTET CONCERT ON IWO JIMA."

"'Come live with me, and be my love.'"

"All my religious musings and ponderings came into a focus."

Stephen Madden is editor of the Cornell Alumni Magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNice Work if You Can Get It

December 1995 By DIANE CYR -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticlePreparing for Contingencies

December 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleControlling Self-Control

December 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

December 1995 By Armanda Iorio

Stephen Madden

Features

-

Feature

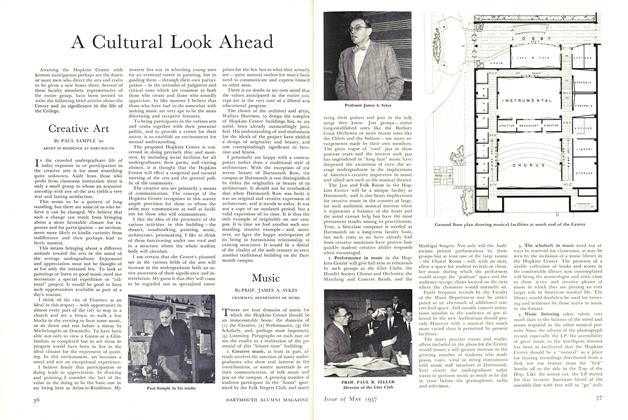

FeatureA Cultural Look Ahead

MAY 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe Cold War and Liberal Learning

November 1961 -

Feature

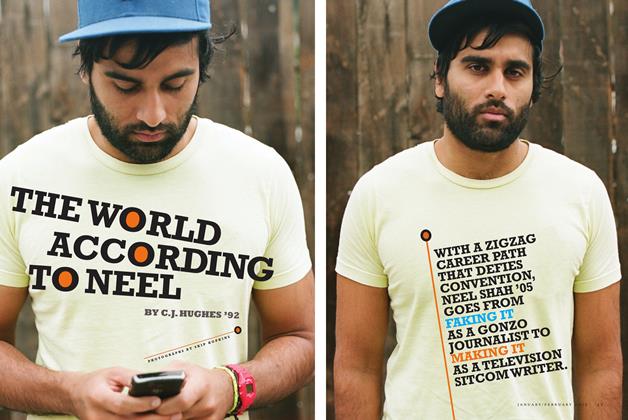

FeatureThe World According to Neel

Jan/Feb 2012 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Merlino Miss

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

DECEMBER • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77