Dartmouth kayakers have won international renownin a sport the College seems scarcely aware of

M ention kayaking to many of Dartmouth's alumni and it will evoke images of Eskimos in flimsy, skin-covered craft hunting narwhales on artic seas. Those who have been graduated within the last two decades probably can recall classmates learning how to propel strange plastic boats with double-bladed paddles and daring to challenge the rapids of roaring local rivers. Yet how many realize that Whitewater racers from the Ledyard Canoe Club have won more individual national championships and U.S. Olympic team berths than the athletes from all DCACsupported sports combined?

Competing without College financing, Dartmouth kayakers of the 60's and 70's compiled an impressive, if often unacnowledged, record in Whitewater contests across the country. During the same period, Ledyard played a primary role in the emergence of the U.S. as a dominant factor in international competition. Today, while the focus of the Whitewater world has shifted elsewhere, the College can still pride itself on fostering some of the top paddlers in the land.

Consider, for example, the case of Eric Evans '72. His name would most likely draw a blank look from those same alums" who equate kayaks with Nanook of theNorth. Based on his achievements in a sport that demands both relentless power and exquisite control, Evans more than deserves to be enshrined alongside such College legends as Myles Lane '28, the Hall of Fame hockey player, and Rudy LaRusso '59, the NBA star. Entering his first kayak slalom race in 1964, he practiced tenaciously and soon rose to the top ranks of whitewater racers. In 1969 he won the slalom nationals, lost the crown the next year, and then captured the title the next eight straight years. Nine U.S. champion- ships in ten years: his is a record with few, if any, parallels in amateur athletics. In addition, Evans was named a member of the 1972 Olympic team, missing a medal at Munich by seconds. He was selected seven times to represent the United States at the biennial world championships.

Asked which of his numerous accomplishments he is most proud of, Evans points to his two first-place finishes at a race in Lipno, Czechoslovakia in 1973, this country's first two gold medals in major international" kayak competition. His initial victory came in the slalom event, in which kayakers must thread their 13-foot' boats downstream, upstream, and even backwards through a series of gates poles suspended 40 inches apart above the surging whitewater. Penalty points are assessed whenever a competitor touches a gate pole with his body, paddle, or kayak, or misses a gate entirely. They are then added to the racer's time for that run. Typically, a slalom course contains 30 or so gates over approximately 800 meters of boiling rapids; contestants must combine speed and finesse for success.

After the first run at the Lipno race, Evans stood eighth in a field of more than 70 of the world's top boaters. He then uncorked the only "clean" run (no penalties) of the day and scored the fastest time through the course, launching himself into first place on the basis of his aggregate points for the two runs. In the process of winning, Evans also finally defeated his two longtime nemeses: Siegbert Horn of East Germany, the 1972 Olympic gold medalist, and the Austrian Norbert Sattler, 1973 world champion. His 26-point margin of victory over the runner-up Horn astounded his foreign rivals.

Yet the "Hammer" (so nicknamed by his Dartmouth cross-country skiing teammates for his excessive poling) was not through with the Europeans. He next won the wildwater competition, a straight dash without gates over a 2—6 mile stretch of turbulent river, achieving a rare double victory. In these two races Evans served notice to the once omnipotent Europeans that he and the U.S. Whitewater team had arrived.

Such was not always the case. When Jay Evans '49 moved his son Eric and the rest of the family to Hanover and joined the College as an admissions officer in 1962, Whitewater racing was a weekend sport practiced largely in open canoes and frail folding kayaks. Evans brought with him one of the early fiberglass kayaks whose durability and rigidity soon revolutionized the art of navigating swift-flowing waters. In anticipation of the spring racing season, he began, teaching himself to tip over and right his boat, a maneuver known as an Eskimo roll, and to paddle the kayak through slalom gates. Evans' enthusiasm soon infected undergraduate members of the Canoe Club and in April of 1963 Ledyard staged the first Mascoma Slalom on Lhat nearby river. Whitewater racing never be the same.

In the ensuing years more and more Dartmouth students succumbed to the lure of the sport, still only in its adolescence in the U.S. Guided by its new adviser Evans, Ledyard quickly established itself as an innovator in the field. During the winter the College swimming pool was opened for practice and, with gates hung from the ceiling, an annual indoor slalom race was started, the first in the world. Borrowing from other sports techniques such as the use of walkie-talkies along the race course and instant results distribution, the Club streamlined its Mascoma competition into one of the premier races in the land, adding a wildwater event in 1966. According to Eric Evans, "Ledyard was the first group to take the sport seriously." Dartmouth paddlers began training and practicing in an organized, disciplined fashion.

Soon the hard work and inspiration began to pay off as Ledyard racers routinely finished in the top ten positions at regional contests. Jonathan Knight '67 parlayed a string of kayak (K-1) victories into a spot on the 1965 U.S. Whitewater team. Simultaneously, Wick Walker '68 was silected to the team on the basis of his performance in the C-l, a craft of a slightly different configuration in which the boater kneels rather than sits and uses a singlebladed paddle. In 1967, Ledyard members Walker, Sandy Campbell '67, John Burton '69, and Eric Evans, then a Hotchkiss student, represented the U.S. at the world championships. Walker brought home the national C-1 slalom title in 1968 and Evans won his first K-1 slalom championship the following year. The DCAC, acknowledging the effort being devoted to the sport, began awarding varsity letters and freshman numerals for whitewater racing in 1969. To this day, however, the Club receives no subsidy from the College and operates entirely on dues and revenues from summer rentals and clinics.

Yet for all the success Ledyard racers had achieved domestically, they were faring no better than their countrymen in competition aboard. While Whitewater racing in the U.S. was at the time in a stage comparable to the infancy of skiing after World War II, the sport in Europe had long enjoyed a status rivaling that of soccer, attracting some of the region's top athletes. American boaters were by contrast inadequately funded, haphazardly trained, and inexperienced, for as Eric Evans observed, "We were explorers back then. We didn't really know what we were doing." Racing head-to-head against their foreign counterparts, U.S. paddlers were routinely thrashed.

Tired of the national team's doormat role, the American Canoe Association moved to redress years of neglect and appointed Jay Evans the first U.S. coach ever for the 1969 world championships. Ledyard members on his squad that year were his son; Burton; Dave Nutt, son of Professor David Nutt '41; and Dave's sister, Peggy. Evans put his racers through intensive training sessions and sent some to Europe-

an competitions prior to the championships. The extra discipline and experience showed to advantage at the Worlds, where four Americans placed in the top ten in their class and the U.S. moved up a few notches in the team standings.

Still, few were entirely pleased with the team's performance, especially in light of the designation of Whitewater slalom as an Olympic sport on a one-time basis for 1972. If the U.S. was to bring home any medals from Munich, American racers would have to be better prepared.

Jay Evans was again named coach for 1971. In the Worlds that year the Americans placed sixth among 23 nations, in part due to rigorous coaching, while the younger Evans took tenth place in a field of 74 in the K-l slalom, by far the most competitive class. Meanwhile, Ledyard paddlers were continuing to excel at the national championships: John Burton won the C-2 (a two-man craft) slalom title in 1970 and took the C-l slalom crown in 1971; Dave Nutt was both K-1 slalom and wildwater champ in 1970; in women's K-1, Peggy Nutt equaled her brother's unusual achievement the same year,, repeating as wildwater queen in 1971;sand Eric Evans captured the 1971 kayak slalom honors, inaugurating his long reign as king of that class.

Thus, by 1972 Ledyard's preeminence in the sport was indisputable, its position the result of a decade of experimentation and dedication that Jay Evans neatly summarizes: "We were new, the sport was new, and we went to the top." Ledyard's leadership continued when Coach Evans took to Europe a U.S. Olympic team that included Dartmouth alumni Campbell, Walker, Burton, and Eric Evans. West German engineers had constructed an artificial race course with gallery seating for 30,000 spectators, the first of its kind, on the Eis Canal in Augsburg, a town west of Munich. The seething, pulsating waters of the man-made rapids bedeviled American paddlers during time trials prior to the games, with many racers unable even to complete the course. In contrast German boaters had practiced at Augsburg for weeks and were often cleanly negotiating the more familiar narrow channel.

The U.S. team persisted, however, and under the watchful eye of Jay Evans, times on the artificial course steadily improved, so that hopes for success at the races were not unreasonable. As it turned out, the American performance at the Olympic competition exceeded just about everyone's expectations. The top Ledyard paddlers were Eric Evans, who took a personal and team best seventh in the center ring event, the K-1, one gate pole touch having cost him a medal; and Wick Walker, who finessed his way through an 11th-place run in the C-l competition. When Jamie McEwan sped to a sensational bronze medal in the C-l, the U.S. became one of only five countries to win a medal in whitewater slalom. The strong showing by the U.S. team and the exposure gained for the sport by network coverage combined to make 1972, in Jay Evans' estimation, "a watershed year for Ledyard and U.S. kayakers."

Whitewater racing has come a long way from those salad days. The results of the 1979 and 1981 world championships confirmed that the U.S. now reigns as the top slalom team internationally and one of the three leaders in wildwater. The early racers opened the door for today's paddlers by proving that yearround training is a prerequisite for success. There is perhaps no better exemplar of that necessary dedication to conditioning and disciplined practice than Eric Evans. During his competitive years his regimen included a grueling schedule of timed gatework in flatwater and whitewater, sprints and distance work, running, and weightlifting. When winter drove him indoors, he would continue weightlifting, paddle in a swimming pool, and ski crosscountry, racing for the Dartmouth team while an undergraduate. More often than not he worked out three times a day, so strenuously that his resting pulse dropped below 50 before the Olympic races. Evans himself describes his program as "fairly brutal" and says "I don't think anyone to this day trained as hard as I did. Smarter maybe, but not as hard."

Ironically, the route that Evans and other Ledyard members paved in the 60's and 70's for today's outstanding racers led to the decline of the Club's prestige in whitewater circles. As late as 1978, Dartmouth could still boast of two national champions when Evans captured his last slalom crown and Bill Nutt '76, brother of Dave and Peggy, won one of his many K-1 wildwater titles. That same year Ledyard kayakers held seven of the top 20 spots in the national slalom rankings and three of the top ten places in the wildwater ratings. The need for more than token training in the much more competitive sport persuaded boaters to look for sites with a year round source of fast-flowing water. Ledyard and its icebound rivers were displaced by outfits such as the Canoe Cruisers Association in Washington, D.C.

While Ledyard may no longer enjoy its old influence in the whitewater world, Dartmouth kayakers still have excelled in this decade. Once such paddleris Bruce Swomley '81, who has continued to devote himself to the sport since his graduation. Swomley began slalom racing as a freshman at the Kingswood-Oxford School in West Hartford, Conn. His brother had bought a kayak and then hurt his knee, so Swomley took over the unused boat and entered his first race. "I did pretty well, I liked it, and from then on the bug bit me," he recalls. His school offered kayaking as a spring sport and he pursued " wholeheartedly, reaching 13th place in the national rankings by the time he matriculated at Dartmouth.

Swomley began training throughout the year once in Hanover and steadily proved his technique and stamina. As a senior he placed fifth at the U.S. team trials and was named an alternate member for the world championships. In 1982, Swomley's run at the team trials was good for second place and a position on the American Europa Cup squad. In that series of races abroad, he stood 18th overall, the highest ranking American. He then participated in the Pan-American Cup, a three-race competition staged in the States and Canada, featuring kayakers from 12 countries. In what he describes as "the biggest win of my career," he won the first race on the West River near Jamaica, Vt., defeating five of the top ten slalom paddlers in the world. He went on to finish fourth in the Cup, again the best American performance.

These days Swomley has his eyes on the world championships in Merano, Italy, on June 12-19- In February he quit a job in Chester, Vt., in order to pour all his energies into workouts and races. He trained for a few weeks in the D.C. area, paddling two or three times a day, looking at videotapes of practice runs, lifting weights, and playing basketball, which he feels helps his endurance and coordination. Thereafter most of his training hours will be spent in his slalom boat as he travels the eastern racing circuit that culminates in the team trials on the West River, April 30 and May 1. Convinced that he can make the U.S. team again, he says, "My goal is to race well at the Worlds. You don't get any other forum for comparing yourself against the best. I'm confident that with a good run I can be right up there with the best that's what I'm after."

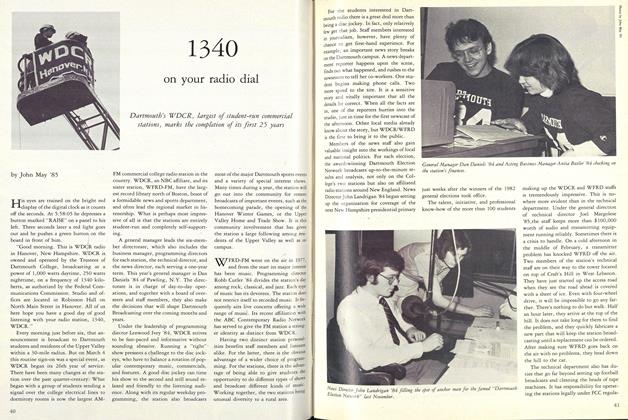

If all goes as she hopes, Dana Chladek '85 will join Swomley on the U.S. team this year. At the 1982 team trials she finished fourth in the slalom event and, because one of the top three women chose not to go abroad, she raced in the Europa Cup, taking the fifth spot in the first race and placing 14th overall. She also shone in the Pan American Cup and was fourth in the final standings for that series. The international experience was a revelation, for she is no longer intimidated by the European mystique. "When I was in Europe last summer and finished fourth," she says, "I realized that those girls aren't that great. There's just more of them." Accordingly, chances are good that she too will compete at Merano this summer.

Born in Czechoslovakia, Chladek and her parents, members of the Czech Whitewater team, defected to the States in 1969 and eventually settled in Michigan. Pushed into kayaking at first by her parents, Chladek overcame her initial fears and began racing at age 14. Attending a series of clinics in 1979, she learned more about technique and training and discovered that "I just kept wanting to do bet ter." The following year she won the junior national title and placed sixth at the national championships. "That's when I started thinking I could make the U.S. team," she recalls.

By the time Chladek entered Dartmouth she was well ensconced within the upper ranks of female slalom specialists. Attracted to the College by both the local rivers and the mountains (she also races for the downhill ski team), she has been more than happy with her choice. Despite the absence of year-round water, she doesn't feel she's at a disadvantage, observing "I think you can become a world champion here."

Like Swomley, Chladek immerses herself completely in her sport. "I'd rather train than go to a party," she says, "because paddling is my first priority." When the nearby rivers flow she puts in at least ten boat workouts a week, along with weightlifting and running. While her immediate goal is to make the U.S. team and go to the Worlds, she prefers to simply concentrate on refining her technique. "I love running gates because it's so precise," says Chladek. "I think the ultimate is being good, seeing what you can do with your body, how fast and clean you can run a course."

So while Ledyard no longer is the whitewater bastion it once was, a few Dartmouth paddlers continue the tradition of excellence. The succession of power should not necessarily be lamented, for as Jay Evans notes, "It's a natural evolution the New York Yankees aren't what they used to be, either. The sport has grown bigger, so it's simply a question of perspective." He does feel students not exposed to kayaking are an untapped reservoir of talent, stressing that "you've got to have not only athletic potential but also intelligence to do well internationally." Evans believes that if the College hired a whitewater coach and financed paddling facilities and equipment, Ledyard could regain its former glory.

In the meantime read the fine print on your sports page and watch for Bruce Swomley and Dana Chladek, two more wearers of the Green tasting the fruits of success.

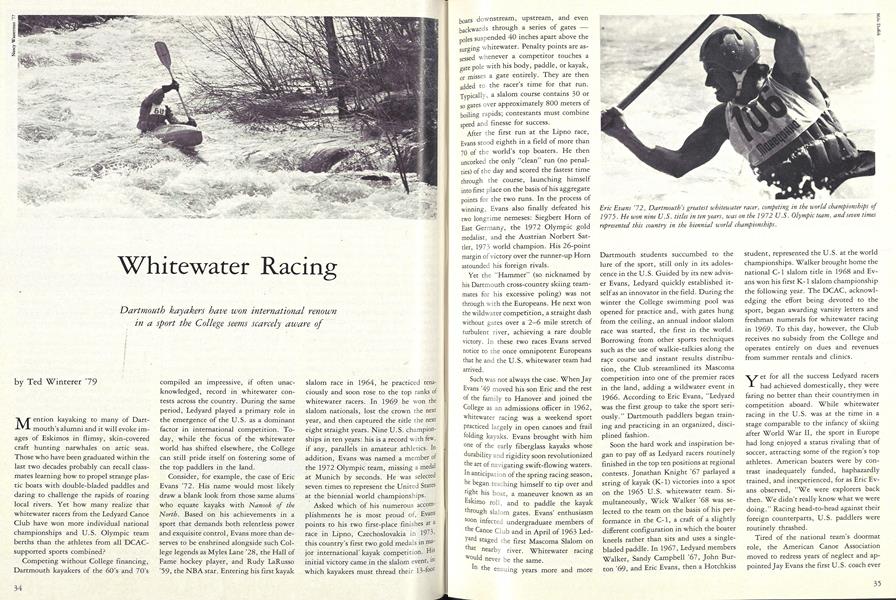

Eric Evans 'l2, Dartmouth's greatest whitewater racer, competing in the world championships of1975. He won nine U.S. titles in ten years, was on the 1972 U.S. Olympic team, and seven timesrepresented this country in the biennial world championships.

Jay Evans '49, the man who brought kayakracing to the Ledyard Canoe Club 20 yearsago, and who led its development as a U.S.Olympic sport.

Carrying on the Dartmouth whitewater tradition is Dana Chladek '85, shown practicing on theMascoma Rlver, She hopes to represent the U.S. at the world championships at Merano, Italy.

Ted Winterer, a free-lance writer based in NewYork City, was active in the Ledyard CanoeClub as a Dartmouth undergraduate and was amember of the varsity kayak team in junior andsenior years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

April 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature1340 on your radio dial

April 1983 By John May '85 -

Sports

SportsSports

April 1983 By Brad Hills "65 -

Article

ArticleThe Arms Race and the Life of the Mind

April 1983 By Stephen J. Nelson -

Article

ArticleRhodes Scholar

April 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleA Universal Concern

April 1983 By Steve Famsworth '83

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClass Association Delegates Meet to Discuss Coeducation

JULY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe Faculty

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureIs Harvard Becoming More Like Dartmouth?

FEBRUARY 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPEAVEY HEAD

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

FEATURES

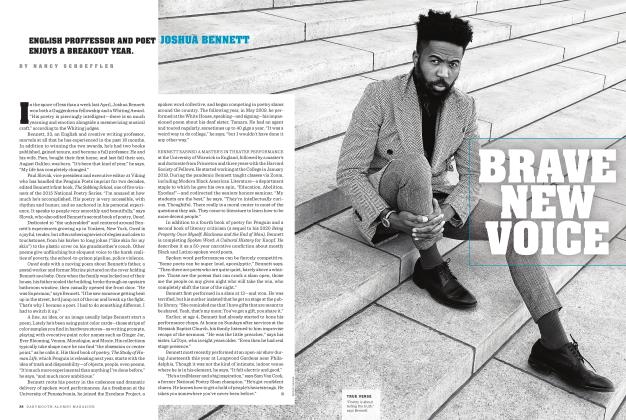

FEATURESBrave New Voice

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2006 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74