Two years ago, when Emory University appointed Maxwell Anderson '77 director of its Museum of Art and Archeology, Emory's President James T. Laney said the museum was "honored at the appointment of such an outstanding and compelling individual as Maxwell Anderson. His scholarly background, experience, and charismatic energy will be a great asset to the museum."

Those who knew Max at Dartmouth will readily understand whence the descriptors "compelling" and "charismatic" come. He had spent five previous years as assistant curator of the department of Greek and Roman art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and before that received his Ph.D. in classical art from Harvard. But Max still recalls the pivotal influence on his career of classics Professor Matthew Wiencke at Dartmouth, where Max's honors thesis focused on Greek vase paintings.

Shortly after his arrival at Emory, Max who speaks five languages and has spent considerable time in Europe—initiated a comprehensive cultural exchange between the university and major museums of antiquities abroad. He began with a long-term loan of Roman marble portrait sculptures from the Aluseo Nazionale Romano in Rome, one of the largest archeological museums in the world, and branched out from there. The exchange program allows Emory to exhibit works made available from the great wealth of material stored in foreign museums, and in exchange, the university sponsors a research or restoration project at the source institution. Initial discussions leading to the exchange project began when Anderson served as a visiting professor at the University of Rome in the spring of 1987.

The Roman marble exhibit went on to win Atlanta Magazine's award for Best Museum Exhibit of the year. As counterpoint to such exhibits, in his first year at Emory Max nearly doubled the size of the museum's staff which now includes seven archeologists and won almost a quarter of a million dollars in grants and outside funding. But the money, staff, and exhibits themselves are not his raisons d'etre. He wants to make his craft come alive to broaden its scope, enlarge and enrich his audience. Kids, scholars the whole of society, really—are all his educational target. "We want to explain the past—make it seem less remote," he says. (Imagine, in the background as he speaks, his most recent show: a full-scale, hands-on Syracuse, Archimedes' Greek city from the island of Sicily. Or the "B.C. Fest" last May, geared toward children, allowing them to recreate an expedition to ancient lands, complete with their games, sights, and raucous markets.) "Archeology is not simply trooping out the mummies."

Regarding his move south Max comments that in contrast to New York City "Atlanta has air you can breathe." He means more than physical breathing: his position at Emory is appealing because it gives him autonomy in setting the direction and policy of the institution he heads. A mentor from his Metropolitan days, Dietrich von Bothner, sums up Max's professional mien neatly. "Some people ... are at their best when they are in complete authority. These people usually desire to get to another plateau. He had opportunities galore [in New York . . . but] there is a lot of interest in Atlanta. And he is a bit of a pioneer."

The Atlanta press has noted this, and taken to him with a gush of Southern hospitality; although Max notes wryly their "insistent concern for my ties" (Italian and paisley, perhaps more common in the Big Apple than in Atlanta). It's the one thing his energetic publicist doesn't include in rhapsodic descriptions of Max's many, and worthy, accomplishments.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBoredom's Uses

October 1989 By Joseph Brodsky -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDon't Call It "The D"

October 1989 By Michael T. Reynolds '90 -

Feature

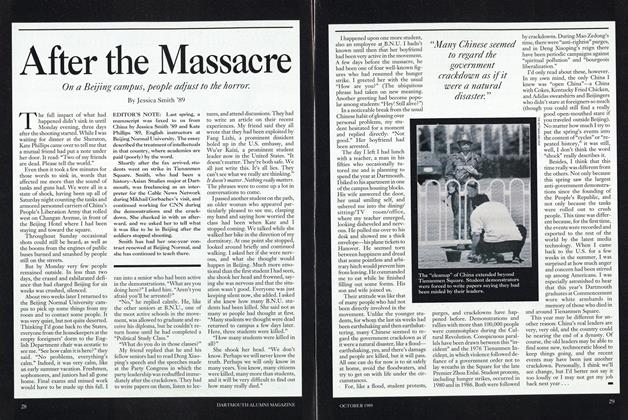

FeatureAfter the Massacre

October 1989 By Jessica Smith '89 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureBUBBLE AND PEAK

October 1989 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1989