IN HIS YEARS AS DARTMOUTH'S president (1893-1909), William Jewett Tucker 1861 enlarged the faculty, charted a modern educational course, and erected the dormitories that made it possible for the school to grow into a national university. But as Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 said at a memorial service after Dr. Tucker's death in 1926, "Bricks and mortar and stone were only minor accessories to the great ends he sought. Tucker added to Dartmouth, said Hopkins, "the qualities of his own spiritual and intellectual self." Among these qualities were a sense of moral responsibility born of the nineteenth century and yet possessing a prescient understanding of the spiritual challenges that awaited in the twentieth.

"Born into the world at a time(1839) when most men regarded the truth as a fairly well settled thing, read an editorial in the November 1926 issue of this magazine, he came to manhood at the moment when Darwin's epoch-making book seemed to unsettle everything."

After graduating from Dartmouth Tucker served as a chap lain for Union troops on their march to Atlanta. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Tucker saw how a united America would expand—geographically, industrially, and spiritually. "The spiritual growth came more slowly," he wrote in his autobiography. Ministering to the Franklin Street Congregational Church in the fast-growing manufacturing town of Manchcstei,New Hamp-shire, Tucker saw how industrial life would bring profound changes to our way of life. As pastor of New York's Madison Square Presbyterian Church, he saw the jarring geographical divisions between rich and poor, and how "social service" was too often viewed as something separate from religious observances.

As a theologian, Tucker embraced Darwin and broadened his conception of God. Rather than a conflict, he saw humanity s vision expanding along with the scientific leaps of the modern world—and an opportunity for a renewal of faith. Not everyone agreed with this vision. In 1886, Tucker and four colleagues on the faculty of the Andover Theological Seminary were brought to trial on charges of heresy by those who challenged a new the ology that embraced science, applied principles of historical criticism to the Bible, and thrust the clergy into the realm of social reform. The controversy dragged on for six years and ended up in the Massachusetts Supreme Court with a decision on the side of religious freedom in 1892, the year before Tucker became president of Dartmouth.

Dartmouth's Trustees, of whom Tucker was a member, knew full well they were hiring a man looking toward the future. "Tucker took the curriculum away from the old classical religious Protestantism of which S.C.Bartlettwas the last great advocate, says history professor Jere Daniell '55. "Tucker had the religious credentials to pull it off and the vision to take the College in the right direction." Just as important, of course, Tucker rededicated Dartmouth as an institution of moral training that, as Hopkins later put it, "revealed alike the love of learning, the worth of moral purpose, and the beauty of holiness."

By now, William Jewett Tucker's dedication to "needful service" exists in the fabric of Dartmouth—and, as every alumnus knows, in bricks and mortar in the foundation created by Dickey and bearing Tucker's name

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhat Does Dartmouth Cry For?

March 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureMoney and Luck

March 1999 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureFirst person

March 1999 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

March 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleExercising the Mind

March 1999 By Rich Barlow '81 -

Sports

SportsSilver Honors for Ivy Women

March 1999 By Sarah Hood '98

Brooks Clark '78

-

Feature

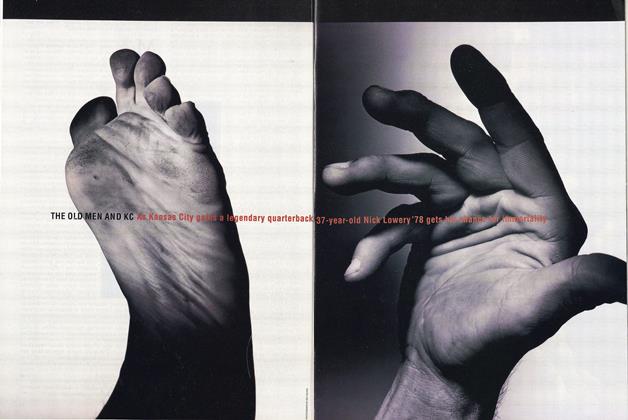

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

NOVEMBER 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleThe Jump to Gotham

December 1994 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPease Out There

MARCH 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPoetry From the Heart

MARCH 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleFAMILY TIES

SEPTEMBER 1997 By BROOKS CLARK '78 -

Article

ArticleReservation for a Clinic

NOVEMBER 1997 By Brooks Clark '78