It is Cabin & Trail initiation night. We hike to Harris Cabin under a hazy and moonless sky for the annual Initiation Feed. Dinner is eaten, songs are sung around the fire- place, and the initiates perform a skit. Meanwhile a snickering bartender mixes secret ingredients in the kitchen. "How are the mungworms this time of year?" one member asks another. The initiates look uneasy. Some have witnessed earlier rituals when novice members choked down mungworm cocktails. They wonder what exactly is the "worm" at the bottom. Mung, they know, is stale beer slime. But a mungworm?

The moment of truth is at hand. A seasoned member reads "The Ballad of the Mungworm Cocktail," an adaptation of a Robert Service poem, and the bartender arrives on cue. As the poem ends, grimacing initiates drink their mungworms down. Non-mem- bers applaud their brave friends and then are ushered out. The mungworms are only a prelude to the mystery- shrouded initiation that follows.

It is, by all a good and proper ritual: tribute is paid to the mighty mungworm, tradition and secrecy are observed, and the initiates share a bonding experience they will remember forever. But wait—this is happening in 1989! Coerced drinking ... possible hazing... somebody alert the Committee on Standards!

Relax, Dean Shanahan. The cock- tails are non-alcoholic these days. The ingredients—subject to the bartender's whimsy—are, well, not noxious, though this time there is some complaint about a fishy aftertaste. The initiation "bonding experience" is based on trust, friendship, and mutual love for the outdoors, not some macho survival trip. Long gone are the days of the "blood-box," which contained initiates who were dumped into a cold lake.

The Cabin & Trail initiation cere- mony is one of many aspects of the DOC's largest, oldest, and most tradi- tion-laden division that have changed with the times. Some traditions survive. Moosilauke is still mecca. Heelers (aspiring members) still drag members into the ski-team shower on their birthdays. But in the past couple of decades much has happened at Dartmouth and in the nation that has come to bear upon students' traditional activities and values. C&T has rolled with the changes.

The unusual willingness of members to adapt their customs and attitudes has had remarkable results. Women are thoroughly and comfortably integrated into the organization, alcohol use has been drastically reduced, and safety is taken seriously.

So is C&T a bunch of puritanical sissies? Well, as a member myself, I may be a little biased. But would weenies oversee the relocation of nearly 24 miles of the Appalachian Trail into a government-protected land corridor, as we have over the past two years? Would wimps build a six-sided shelter on Mt. Cube—mostly built over the summer? Would the timid or lazy lead trips to the mountains every weekend and care for more than 85 miles of trail, nine shelters, and eight cabins? While attitudes have changed, and some traditions have been revised, the level of motivation and enthusiasm has clearly not declined. C&T is like a restaurant that has changed its decor but still serves the same food.

But what does C&T's "decor" of traditions have to do with hiking, trail work, and shelters, anyway? I wondered this myself when I walked into my first meeting in the fall of 1985. It was the silliest meeting I had ever attended. People wore strange clothes, "Council Minutes" had nothing to do with the previous meeting and contained wild distortions of the past week's events; upcoming trips were announced in mock-epic terms; awards were given for particularly blunder- ous behavior; and inside jokes abounded. I got what I came forinformation about hiking but was much more intrigued by the antics of the people clustered around the Council table. They seemed to share some-thing special. What the heck was going on?

The next week I found myself in the woods, miles from campus, being instructed by Alex Tait '86 in the basics of chainsaw use. I wasn't quite sure how I'd gotten there. I had come to Dartmouth from a midwestern suburb; I had taken an interest in hiking; I had gone to a strange meeting; and now I was holding a chainsaw. I mused about the mysterious ways of cause and effect. But Alex had announced a trail seminar as if he was inviting us all to a party. Of course I signed up. After this glorious introduction to C&T, I quickly became immersed in its ways and determined to complete my "heeler requirements" as soon as possible. (Requirements for membership are geared toward acquiring skills for outdoor survival and leadership.)

Still, an invitation has to be worded in a way that is attractive to the invited. That hasn't always been the case with C&T. During the freshman year of Sally McCoy '82, another female heeler told her that a woman would not hold the chairman's position during her time at the College. Sally later became the first female chair. After her, a succession of two more women, and later a third, would fill her position. As much as she disagreed with what she had been told, Sally wasn't out to prove anything—she just felt that she was the person for the job, and that the other members would agree. By the time she was elected, Sally says, "They elected me. The fact that I was a woman was not an issue."

The transition was not immediate. Bernie Waugh '74 recalls that his sister, a '76, and her friends did not feel at home in the definitely male atmosphere of C&T, though attempts were made to make them feel welcome. Part of the problem, Waugh says, was that the camaraderie of C&T was based largely on "the shared hardship of not having any women around." Instead of facing another dateless Carnival, C&T men would go out together and "do something really rugged."

Nevertheless, compared to the rest of the campus, the integration of women into C&T's activities and social structure was rapid and relatively painless. Even before the College went coed, transfer women had competed in tests of logging skill through C&T's intercollegiate Woodsmen's Team. Women quickly became involved in all sorts of C&T activities, and were known to be just as boisterous, filthy, and hard-working as the men. Some even chewed tobacco. They too could be "grimbos," or regular guys. In Sally McCoy's time women finally worked their way into the more esteemed council positions.

By the time I arrived on the scene I was impressed by the integration. Women weren't wielding axes to show that they could be "one of the boys" they were just getting some work done. (Happily, tobacco chewing had gone by the wayside.) The rest of the campus was often embroiled in debate over sexism and the alma mater, but in C&T gender was never an issue.

Well, almost. There was one more bridge to be crossed.

As all of C&T geared up for the spring 'B6 Woodsmen's Weekend, the annual intercollegiate event that comes to Dartmouth every three years, one woman decided she'd had enough of this woods men stuff. Though she was an essential sixth on the women's team, she refused to compete unless the name of the competition was changed to something less gender-specific. The Women's Issues League also protested the name. After a little debate and some quiet grumbling about "what's in a name" and "a rose is a rose is a..." the membership decided it was time for a change, and the 1986 Wood craft competition came into being. A good time was had by all. The team later changed its name again, be- coming the Dartmouth Forestry Team. The women's team is now pleased to have on record that it blew its competition out of the water to take first in 1989's Dartmouth Logging Days, beating the top men's scores in two events.

Perhaps a more subtle effect of the age of coeducation has been the increased emphasis on safety in DOC activities. "We used to do a lot of dumb macho things," Sally McCoy told me, "like haul propane tanks into cabins at the spur of the moment at night." (Pro- pane "bombs" weigh about 200 pounds.) One dumb macho thing, an underwater swimming contest, claimed the life of a C&T member during McCoy's time at Dartmouth. While director of Outdoor Programs Earljette has brought the administration's safety concerns to DOC leaders and has worked with them to develop programs and guidelines, he still keeps his distance from actual decision- making. He likes to say: "You give students enough rope to hang them- selves by, then stand close enough to cut them down before they do." Earl maintains that the DOC is unique for the autonomy of its student leaders and the level of decision-making. Tragedies are not prevented by rules and regulations; Earl realizes that it is up to students to develop the awareness and attitude to prevent accidents.

C&T decided on its own to make first-aid training a requirement for membership, and it has worked with the DOC student safety director and Outdoor Programs to sponsor seminars in back-country emergency response and firefighting. The training students receive, the autonomy they are allowed, and the value placed on prevention are in- strumental in the development of competent and confident—but not cocky— outdoor leaders.

I'm one of the beneficiaries. When I was an undergraduate, the fun and camaraderie were the most important parts of membership. But in the years ahead I suspect I will benefit most from the tremendous gain in self-confidence. C&T showed me the depth and limits—of my strength. I have learned that I can carry a heavy load, hike long distances, lead others, competently handle and adapt to adverse conditions, and deal reasonably with pain. I have learned that I am not fragile but am most definitely mortal.

Along with safety comes less alco- hol. Beer and axes are just not a good combination. A "Piss, Pass and Boot" award no longer makes the rounds among Forestry Team members. The group has even turned a wary eye toward alcohol in meetings. Jeff Garneau '85 told me that when he was a freshman there were kegs at almost every meeting, and cups of beer were passed around aggressively until the keg was empty. Some people brought bottles or cans to drink before the meeting started. Everybody got ripped. It didn't take a dean to see that this was not necessarily conducive to C&T's mission of "promoting fun and fellowship in the out-of-doors." Garneau and other members from earlier days talk about a "drastic" decrease in alcohol use from their freshman to senior years. This is mind-boggling to me, considering the ridiculous amount of alcohol I saw consumed at some meetings during my freshman year. Since then I have seen the offerings on the Council table shift from kegs to cases, and later to sixpacks, and still later to Ben & Jerry's ice cream. Nobody seems to miss the beer much—an occasional Weideman's will do. Perhaps three years from now the '92s will look back at their freshman year and say in horrified whispers, "Sometimes they even drank beer during meetings!" Or maybe they will accuse us of milk-fat abuse.

But don't get the wrong impression. We may be sober, but we're not prim. Tom Slocum '82 once wrote an an- thropology paper about a C&T meeting ing, asserting that members' distinctive dress, rituals, and general outlook placed them in a distinct subculture. They wore dumpcoats (long wool coats found in a dump or a rummage sale), sang bawdy songs, had their own vocabulary, and bore a reverence for sharp tools. C&T customs are like any other at Dartmouth in that they come into being as a source of unity as well as a mark of distinction. The difference is that C&T's personality is vital to its continued existence, not just to distinguish it from, say, the Harvard Outing Club (there is one, you know). Hiking is fun, but anybody can do it. Trail work is also immensely satisfying at times, but you'd probably never know that unless you felt from the beginning that you would be swinging a machete with people you really wanted to be with. For that same reason, C&T does not spend much time in debate over the relative merits of its practices and rituals. There's work to do and fan to be had, and enthusiastic people are needed. If something is causing discomfort or hostility, it changes or it goes.

Like other Dartmouth alumni, C&T old-timers are not always happy with the changes they see, but if they take the time to ask, they find that C&T still inspires the same feelings. Sally McCoy, in the days of kegs and chewing tobacco, and I, in the dawn of lycrawear and male knitters, first fell in love with the members of C&T for the same quality—their "aura," in her words, of "authenticity and understatedness. " Chubbers of every era have their memories. Bernie Waugh still laughs about eating ice cream pie with an ice axe in the snow near the summit of Sandwich Dome. Jeff Garneau still savours having spent a last night in McKenney Cabin and then burning it down the next day, standing back to watch the usually taciturn Earl Jette dance amidst the flames. (I wish I'd seen that!)

To show me how she felt about C&T, Sally McCoy directed me to a passage from E.M. Forster's essay, "What I Believe." She described C&T in Forster's words, as "an aristocracy of the sensitive, the considerate and the plucky," who have a "secret understanding...when they meet," and who, above all, "can take a joke."

With all that, you'd think that we'd be heralded as a campus test-farm for progressive thought. But no. The woodsman image still haunts us.

We once found ourselves the target of a cranky newspaper columnist, Clay Nichols '89, just because we were using a chainsaw one Sunday morning outside his window (we were preparing for Dartmouth Logging Days). Next day in The Dartmouth was a column titled, "The Dark Side of the DOC." Mr. Nichols described us as solitary forest folk unacquainted with the social graces of human society. We had an "earthy hue," he said. ("AAAAGGHH!!!" I screamed. "I've been stereotyped!") Instead of a sensitive aristocracy, we reminded Nichols of frolicking Ewoks ("furry little Star Wars creatures who live happily in hollowed-out tree trunks").

He said he just wanted a little consideration, such as we might show a beaver. Lucky for him, we toyed only briefly with the notion of granting his request. "You wouldn't want to bother beavers with that chainsaw, would you?" he wrote. Of course not. Dynamite is the way to keep beavers from making swamps of our trails.

The matter of the article was touched on briefly at the next members meeting. Maybe we should write a rebuttal, somebody said. Maybe we should let people know just how progressive, sensitive and downright human we actually are.

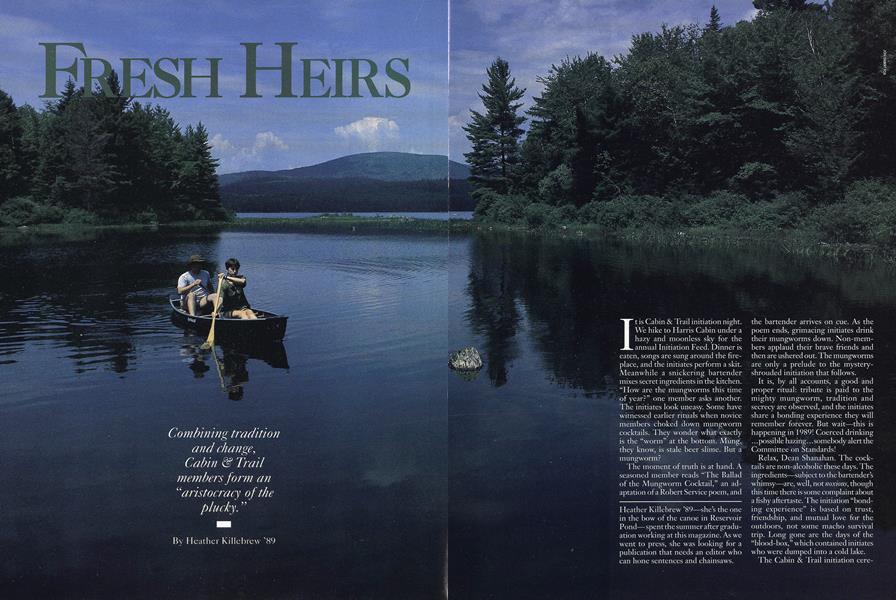

Combining traditionand change,Cabin & Trailmembers form an"aristocracy of theplucky."

Straddling the Connecticut River, the 75 miles of Outing Club-maintained Appalachian Trail features Velvet Rocks and a chair made of granite.

Women competed on the intercollegiate Woodsmen's Team even before the College was fully coeducational.

A freshman trippie crosses the Baker River in '75. The changes began in the mid-seventies.

In the early days of coeducation, some Cabin & Trail women chewed tobacco along with the men. Now it's okay to be different and still equal.

Heather Killebrew '89—she's the one in the bow of the canoe in Reservoir Pond—spent the summer after graduation working at this magazine. As we went to press, she was looking for a publication that needs an editor who can hone sentences and chainsaws.

"I had come toDartmouth from amidwestern suburb;I had taken aninterest in hiking; Ihad gone to a strangemeeting; and nowI was holdinga chainsaw."

"Instead of a sensitivearistocracy, wereminded him offrolicking Ewoks."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMaking the Normal Less Normal

November 1989 By Warner R. Traynham '57 -

Feature

FeatureA Foreign Correspondent's Essential Skill: Packing

November 1989 By Christopher S. Wren '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Day I Got Chewed Out By Red Blaik

November 1989 By Rodger S. Harrison '39 -

Feature

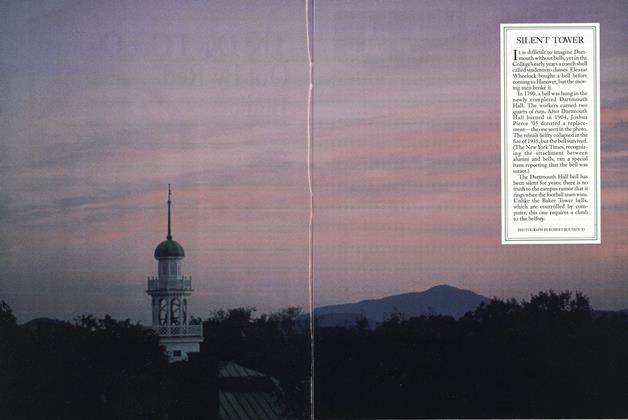

FeatureSILENT TOWER

November 1989 -

Cover Story

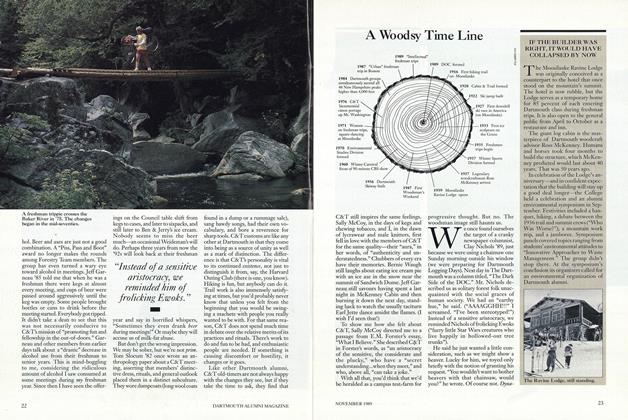

Cover StoryA Woodsy Time Line

November 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFashion Corner: Two Outing Club Looks

November 1989

Features

-

Feature

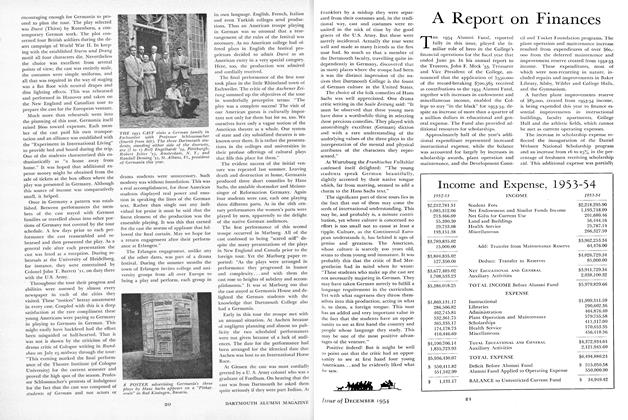

FeatureA Report on Finances

December 1954 -

Feature

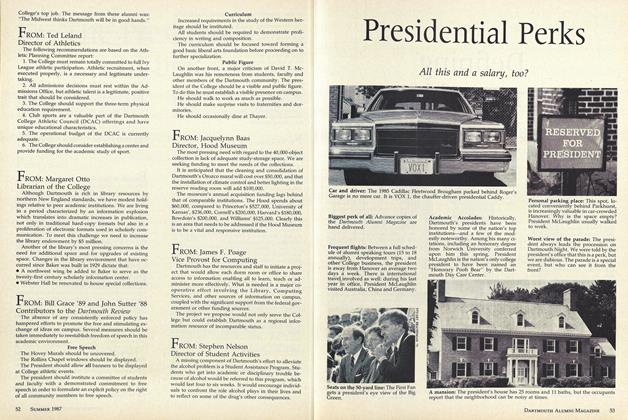

FeaturePresidential Perks

June 1987 -

Feature

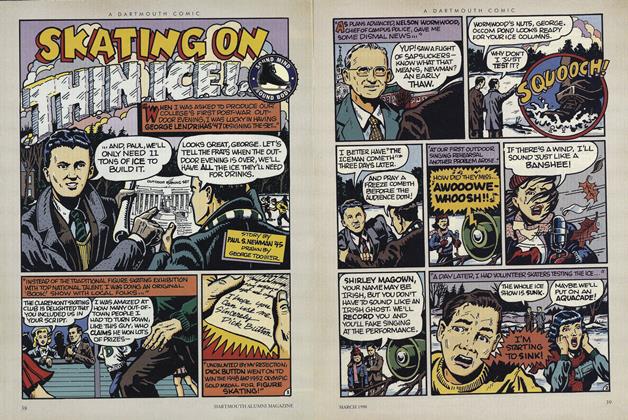

FeatureSKATING ON THIN ICE!

March 1998 -

Feature

FeatureRoommates

SEPTEMBER 1999 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR KIDS OUTDOORS WITH HI-TECH GIZMOS

Jan/Feb 2009 By DERRICK CRANDALL '73 -

Feature

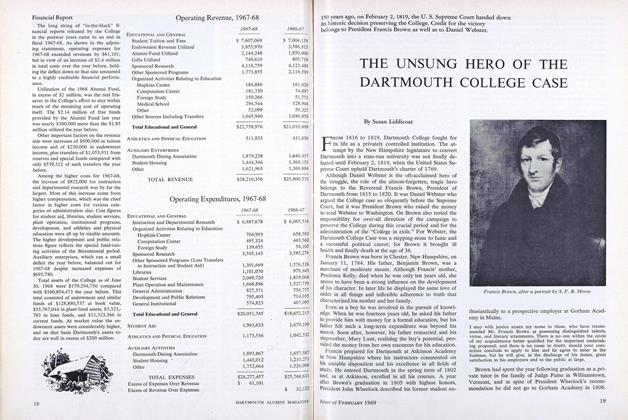

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

FEBRUARY 1969 By Susan Liddicoat